The blind poet Milton, praying for divine inspiration, tells us what he misses most since losing his sight:

Thus with the year

Seasons return, but not to me returns

Day, or the sweet approach of even or morn,

Or sight of vernal bloom, or summer’s rose,

Or flocks, or herds, or human face divine.

The things of beauty build to a climax, the human face divine, the most glorious thing in all of physical creation, if we have eyes to see and a heart to love. The noun is bracketed between the adjectives human and divine, as is proper, because man has been made in the image and likeness of God. If we know what is most human, we will see a reflection of the divine. So when Satan sees Adam and Eve for the first time, his eyes are drawn to the locus of their greatest beauty and glory:

Two of far nobler shape erect and tall,

Godlike erect, with native honor clad

In naked majesty seemed lords of all,

And worthy seemed: for in their looks divine

The glorious image of their Maker shone:

Truth, wisdom, sanctitude severe and pure.

The Hebrews were enjoined most strictly never to reduce God to a created form, a product of the human imagination, carved for display, yet the psalmists yearn to behold the face of God, and to dwell in peace before His countenance. God is thus revealed as intensely personal: the source and the aim of all genuine personhood. But those who turn away from God, putting all their stock in riches—and we may assume that the rich in those days were like the rich in any day, and that much of their pleasure in wealth lay in its display before the less fortunate—will become or have already become “like the witless beasts,” who have no understanding. “They are herded like sheep into Hell,” says the psalmist. Entire cities may flash and gleam with wealth, may enjoy granaries full to bursting, and may be called blessed, but in themselves these things are all empty. Blessed rather are “the people whose God is the Lord.” All through the Psalms we feel that thirst for intimate friendship with God, the pain when He is felt to have abandoned the soul, the comfort of His presence, the joy even of such mediated communion as the poet feels when he enters Jerusalem, or sacrifices at the temple, or lies upon his bed at night and ponders those personal gifts, the ordinances and precepts of the one and only Teacher.

In what kind of world has the human being been de-faced? Not in the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. Look at Giotto’s Nativity in the Arena Chapel in Padua. Mary holds the infant Jesus before her, at some extension of her arms, the better to gaze upon his face, and he gazes upon her in turn, intently. Theirs are faces of concentration, personality, life: and certainly Milton’s words apply to them: Truth, wisdom, sanctitude severe and pure. Or look at any of the great oil portraits painted by the Renaissance masters. There is Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, the essential wise man, large eyed, with a heavy beard, mild in countenance, penetratingly wise and yet benignant. There is Titian’s portrait of the young man with the glove: stern, thoughtful, intelligent, reserved, as we sense from the fact that one of his hands is still gloved; even menacing. He is a man born to rule. Everyone in the West knows the face of the Mona Lisa. Everyone should know the face of Christ painted by Rembrandt, his head tilted, his eyes expressive of an infinite patience with sinful and foolish man, tinged with disappointment, judgment, and mercy.

As late as the black-and-white movies that Hollywood produced for several decades—decades of wild wandering there between virtue and the grossest evils, between a foundational faith in the God of our fathers and an all-eating atheism—the focus is often on the human face and the hands, to touch upon the mystery of the person. So in A Tale of Two Cities we see the remarkably expressive face of Ronald Colman, standing on the sidewalk on Christmas Eve as the snow falls, looking into the camera as he thinks about the woman he loves but who cannot love him in return as her husband; hearing the strains of Christmas carols he cannot join; watching as people pass by him on their way to church. Or the face of Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night, young and full of love but not for the flashy man she is supposed to marry, as she proceeds in her wedding gown toward the fateful moment, and her father whispers to her that he has a car waiting over yonder in case she wants to marry the man whom she really loves—and whom the father approves.

I mention those movies advisedly, because the faces of men and women themselves suggest that the sexes are made for each other, in a love that is holy and chaste. People now will sneer at the self-censorship that Hollywood engaged in, but it produced movies of extraordinary subtlety and acute attention to the reality of sex—not the act, which the witless beasts engage in, after all, but male and female, the elemental kinds of human being, each incomplete without the other. The moment with Ronald Colman is painful and noble at once, only because the woman he loves, Lucy Manette, is innocent and pure—there can be no thought here of fornication or adultery. Claudette Colbert knows that if she goes through with the wedding, that is that, and she will never again enjoy the electric attraction she feels for the mere newsman Clark Gable. She will be reduced to a name in the society pages of the newspaper. She will be a new item in her rich husband’s collection, an objet d’avertissement.

Now, then, what happens when we cut the cables that bind us to God? Or, more precisely, what happens when we no longer feel that we are made in God’s image, when Milton’s poignant cry no longer makes sense to us, because we no longer are in touch with the mystery of the human face? When truth, wisdom, sanctitude severe and pure are mere words to us? When the first part of the body we look to is not the face but something else? What form does it take, our becoming like the witless beasts?

In our time, I think, the form is self-advertising and pornographic. If in the old movies we covered the genitals and exposed the face, in pornography we cover the face and expose the genitals; the face is but an accessory to the genitals. The face advertises the genitals, or whatever it is that the person employing the face does with them. We do not gaze lovingly into the eyes of another person. We gaze obsessively and reductively upon a mere part, forgetting the face.

Therefore, when I use the phrase “self-advertising,” I do not mean to suggest that there is an independent self to advertise, a self that shines through the human face. There is no human being without the web of relationships into which he has been born, including his fundamental dependence upon and orientation toward his Maker. If we deny this, if we deny the claims of history, kin, family, church, and God Himself, we do not emerge independent. We fall into the void. We claim to be “finding ourselves” by cutting our ties, and discover instead that there no longer is a self to find. We do not see our own faces.

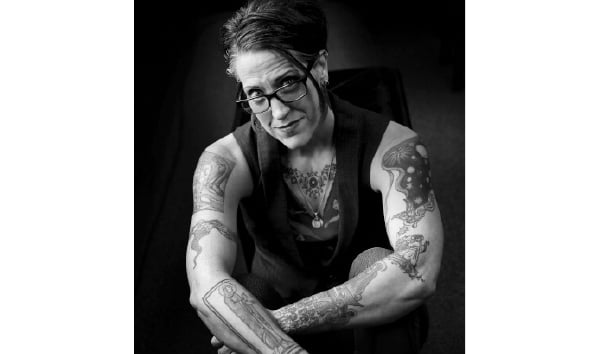

When I was a boy, some working-class men had tattoos, usually unobtrusive, on the inner forearm or near the shoulder, memorializing some loved one, or their service in the Navy. That was all. It was a kind of self-branding, like the notch on the earlobe for braves in an Indian tribe. It was not a branding of the self, turning the self into a “brand” to advertise. Now, by contrast, tattoos are everywhere. It is not that people sport tattoos where the sun doesn’t shine. It is that they sport tattoos where the light of the face should shine, and everywhere else too, so that the very self is made subordinate to the advertising. There is no independent self to express. The medium is the message: The tattoo is the countenance; the advertisement is the self.

This explains the difference between parades such as our parents and grandparents knew them, and a parade now. In an ordinary parade, people wear the uniforms of the Knights of Columbus or the Army Reserve not to advertise their persons, but to celebrate their solidarity with one another in a common fraternal bond. In a parade nowadays—for example, a gay-pride parade—each participant is supposed to present himself or herself as unique, but not as the unique instantiation of the image of God. The face then disappears. The masks prevail, including the mask of nudity. For public nudity is meant to obscure the face, to redirect attention away from the eyes and the countenance and its thoughts and hopes and sorrows, toward a sort of detachable, interchangeable, disembodied body: a collection of body parts on parade, abdominal muscles, flanks, buttocks, genitals. Each participant strives for an epiphanic effect. “Look at me—I exist!” they all cry with a pathetic intensity. But it is a sham. What we see are not persons but the advertising: strange hats, plumes, leather underpants, men in dog suits, women with crew cuts, people led on leashes, spiked collars, pierced noses.

When I was a boy, I did not identify as a boy. I simply was a boy. That was a physical, biological, and social fact. It was a part of the reality that I rejoiced in, as I loved such things as the glacial rocks and the rushing streams of Pennsylvania. I could no more change that reality than I could declare that the sky was yellow instead of blue. And why would I ever want a yellow sky? If you wanted to know me as the particular boy I was, you would have to talk to me: You would have to look at my hands, my eyes, my face. A great portrait does not need advertising. It simply is what it is. You do not assist Raphael’s portrait of Castiglione by gluing a caption to the wise man’s forehead. You do not turn Mona Lisa’s cheek into a billboard: “Female Mystery: Get Some Now!” These would quite literally be acts of defacement.

The thing about such defacement is that it cannot achieve its end. You cannot scrawl in great letters on the side of a church, “Holiness Here!” The holiness of the place either shines through its noble structure, or it does not. If it does, the advertisement distracts, in the literal sense of the word: It pulls apart, it wrenches our attention away from the church’s inherent beauty. If it does not, then the advertisement is merely absurd, like a flashy gold ring in the snout of a pig. It is the same thing with the “identities” our young people are encouraged to embrace and burden the world withal. If your personhood does not already glow forth in your countenance, no defacement can help you.

And here is the trouble: This explains the dreadful fear that the defaced feel when people do not bow to the advertisement. If I am selling lemonade, and I put a big sign in front of my stand, and you pass me by, I know that somebody will come along and buy a glass. And in any case, I am not my lemonade. But in our contemporary world of the defaced and the faceless, we are supposed to sell ourselves, precisely when our sense of self is most tenuous; there are no selves to sell except the selves that are created out of airy nothing by our restless advertising. If, then, people pass us by and do not use the pronoun we insist upon—do not show appreciation for the billboard of the body, do not play in the fantasy world of our own sexual commercial—then where are we? It is why the sexual self-displayers can say, without any sense of absurdity, that when we deny that a man is “really” a woman or vice versa, we deny their very existence. That is because they sense that they have no existence apart from the fantasy. There is nothing behind the billboard.

And just as there is no end to advertising, because what seizes the attention now is dull and neglected tomorrow, even quite invisible, so there can be no end to the multiplication of sexual advertisements, with stannous fluoride and everything. One tattoo must overdo another. One identity must distinguish itself from the old ones. Every single person who has stepped into the sexual void must secure an identity that is new and improved, hot, on sale, all the rage, unusual, brave, radical, avant-garde. The very incomprehensibility of each new identity is a miserable parody of what is unfathomable about personal being. But the old defacement, like old pornography, and like old methods of advertising, will not suffice. Who buys Ovaltine now? If there are 30 “genders” this year, there will have to be 300 next year, with identity growing more and more fissiparous, like the scattering and dissipation of molecules in a universal heat death.

Leave a Reply