Are we currently at war with militant Islam? Not in the same way we were with the Germans in World War I and the Japanese and Germans in World War II. In the two world wars, it was a people against a people, tribe against tribe. Our hatred for the enemy was passionate and pervasive. Allied governments stoked the fire with stories of bogus atrocities, more primitive, perhaps, in World War I. A widely circulated cartoon showed the kaiser’s troops, with monster faces, crucifying an Allied soldier and bayoneting a baby. As one British general explained it, “to make armies go on killing one another it is necessary to invent lies about the enemy.”

In World War II, the news media and Hollywood featured the same kinds of stories—toned down a bit, but designed to inflame hearts with unreasoning anger. We became, all too quickly, a hateful people, though—as our British ally suggested—in wartime, a certain amount of hatred is all but mandatory.

Warfare is necessarily personal, though never intimate—like sex between strangers. I remember reading an account of a man attending an orgy for the first time, guided by an experienced friend, who—in the midst of the heated activity—pulled him off a woman he knew, saying, “Come over here. I want you on top of someone you’ve never met.” That’s war, being on top of someone you’ve never met—a catastrophic encounter with another human being that has dreadful consequences, yet thrives on anonymity. You’re out to end the life of someone you know nothing about—someone’s husband, wife, father, mother, son, daughter—with a complicated history you’ll never learn and couldn’t possibly understand. Yet it’s frighteningly personal—a tragedy one person inflicts on another, the ultimate indignity.

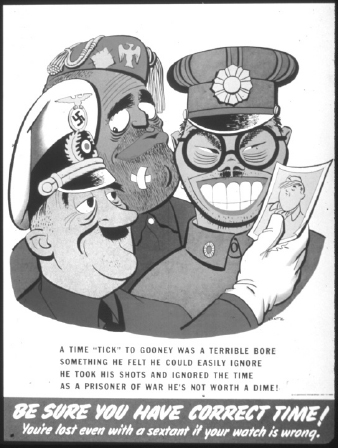

And most of the pro-war propaganda was designed to make us forget the personhood of our enemies, to submerge it completely in the stereotype. The result was a nation populated by haters angry at stereotypes—just what government wanted us to become. Otherwise, how would we become the “Greatest Generation” and make the sacrifices necessary to win the war?

I think old ladies were the most vicious. They would come up to young men standing at the bus stop and demand to know why they weren’t in uniform. One of my cousins, desperate to enlist, was classified 4-F because he was asthmatic. From that day forward, he was afraid to walk down the street for fear of being attacked by crones with umbrellas. It happened more than once. He finally got a job in Washington, where men in civilian clothes were assumed to be FBI agents or inventors of bombsights.

I remember sitting in a theater with two other boys, watching a war movie. The hero, a knife between his teeth, was creeping up behind a Japanese guard—slowly, silently. Even the mood music had ceased. No one in the theater dared breathe. Then, as he took the knife and raised it on high, suddenly from right behind us a voice shrieked, “Kill him!” Simultaneously, our three hearts stopped. We turned around to see a white-haired old lady, her ancient eyes burning with malice.

In the movies and on radio, Germans were depicted as coldly cruel and sometimes even buffoonish with their military swagger, goose-stepping, stiff-armed salute, and mindless devotion to Adolf Hitler. One song, “Der Fuehrer’s Face,” was a hit for comic bandleader Spike Jones: “When Der Fuehrer says, ‘We ist der master race’ / we hEIL! hEIL! right in Der Fuehrer’s face”—each heil followed by the sound of breaking wind.

Charlie Chaplin’s 1940 movie The Great Dictator reduced Hitler and Nazi Germany to the stuff of comedy, as did the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup and Jack Benny in To Be or Not to Be. However, when the torn and charred bodies of Americans began to come back from Europe in ever-increasing numbers and news of the holocaust spread, we no longer felt like laughing at Nazis. Later movies—including those made after the war—depicted them as robotic ideologues, who killed the innocent out of a cold and brutal illogic.

During most of the war, it was the Japanese whom Americans hated the most—perhaps because they’d bombed Pearl Harbor and started the whole mess, perhaps because they looked less like us than the Germans and Italians. Or perhaps because more of our boys were killed in the Far East than in Europe.

In the movies, the Japanese weren’t pictured as menacing people, so much as crazed animals. The mostly Chinese actors who played them charged around the screen with maniacal faces, slaughtering not only American troops but women, children, and three-legged dogs. When they were mortally wounded, movie-Japs shrieked, flailed their arms, and twisted their faces into masks of pain and horror. At these moments, audiences would applaud wildly. Hollywood played to our passion for vengeance; as a consequence, John Wayne killed more Japanese on the screen than real-life Marine regiments did. Today I admit I like to watch these old movies on TV and can still muster a little of that old thrill, when a Zero pilot gets drilled in the chest and begins to scream and spout blood.

I believe the success of The Bridge on the River Kwai (Academy Award for Best Picture, 1957) can be attributed in part to the residual rage the Japanese stirred in us more than a decade after the war. We gloried in the humiliation of Colonel Saito, played by Sessue Hayakawa. In the blowing up of the bridge—built by American and British prisoners of war—we saw the righteous destruction of the Japanese Empire.

More to the point, when the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, everyone I knew—with the exception of my mother—cheered, danced jigs, exulted. We had finally and appropriately repaid the little yellow bastards for Pearl Harbor and for all the eyeless, speechless American dead, lying in their stone boats beneath grass in cemeteries all over the Far East. I could name the ones from our town, remember the color of their eyes and the sound of their voices. So could most Americans remember their loved ones, their dead. We still can, those of us who are left.

Younger Americans now agree with my mother: The introduction of nuclear weaponry and the incineration of some 66,000 human beings was an atrocity—a war crime committed by a whole nation acting as the Avenger of Blood. In my cooler moments, I know that’s probably right. But my heart is still afire with a quenchless anger. And for that anger—perilously close to hatred—Hollywood bears much blame.

Leave a Reply