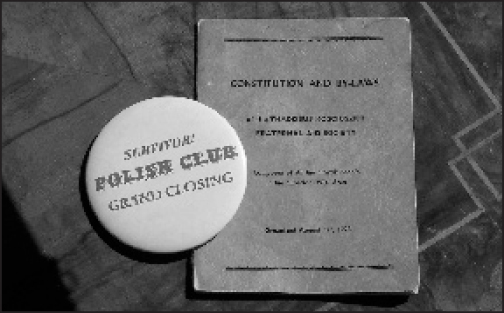

I can’t forget the sorrow of my lodge brothers when the doors closed to our beloved home. We had to pay a bill for a new roof, then the ice machine in the bar went on us. When the jukebox broke, we couldn’t play “Poland Shall Not Perish While We Live to Love Her.” Neighbors around 1901 Broadway won’t hear the anthem come again through the windows of the Tad. Kosciuszko Lodge and Polish Club, founded 1928.

March, march, Dabrowski

From Italia’s fair shores,

Back to join the nation,

Back to Poland’s broad plains.

With all of us tired and sick, we couldn’t drive or walk no more to meetings or to the Polish Club bar for a shot and a beer. I am one of the young members. Wojciechowski is fifty-four, seven years younger than me. Lisak is younger. For the rest of them in the Club, they complain, and rightfully. They say, “Starosc nieradosc, Old age is no good.” They stay at home behind locked doors. No new members, no new dues to pay the light and heat bill.

At the bitter end, Miernickis made up half of the Polish Club. If you had eighteen lodge members present for a meeting, nine were from their family. Now, with the Club out of business, they should organize a Miernicki Fraternal for themselves. They could say, “If that’s what you want, you non-Miernickis can have your own auxiliary.” At every meeting almost, they won the twenty-four-dollar dues board, the eighteen-dollar attendance prize. Money goes to money. That one, Paul Miernicki, age seventy-seven, cried out, “Jezu kochanej!” when we closed the doors of the Club. We told him, “Things will get better, Paul Miernicki.” We said to him, “Smiech to zdrowie, a zdrowie to grunt . . . Laughter is good health, and good health is all.” Nothing comforted him.

I say, “Laughter is good health,” when, in damp weather, my fingers are sore. My hands are swollen so bad that it’s hard to play. I practice for my wife, your mother, Tadeusz and Karen. In the kitchen, your mother and I sit at the table, look at your empty places, and feel lost. You are grown-ups, but she puts out an empty bowl for your soup, whether kapusniak, beet, or mushroom soup. Someday, you will be with us when you have a vacation from work.

As I practice my old songs after supper, she does the dishes. Tonight, we had bigos, hunter’s stew. It smells like meat and cabbage in here. Laughing, I tell her that with my schottisches, I am repaying her for the fine supper. (I tell you privately, it is not always much fun for me. Yesterday, I felt crippled enough in my arms and wrists that she had to get the accordion out of the case for me and help me with the straps. I played “Dreamer’s Waltz.”) I have good news to report, too, though—not just that everything is bad at the Kosciuszko Club and that my hands are sore at the house.

Actually, I have three good-news things to tell you. The South Superior Market expanded the meat case. Your mother and I waited for this. Final remodeling is done. You should see in today’s paper, it says the market has added “36 ft. to give us 66 ft. total, making us the largest full-service meat department in the Northland.” That market is “Home to Award Winning Sausage.” On top of the counter are three Wisconsin Association of Meat Producers plaques. In the “Smoked and/or Cured Small Diameter Sausage” class, the market won a Champion’s Award for their apple bratwurst. I’ll try to send the ad. We were first in line today. She wanted good meat, and, in the produce case, we spotted a head of cabbage. They have expanded the produce service as well. In bigos, you use beef, pork, white cabbage, salt, butter, onions, an apple or two, etc. (Remember how your ma sometimes substituted sauerkraut?)

Other good news is that the church at Belknap Street and Hammond Avenue across from the courthouse reopened. Presbyterians held it for years until it shut down like the Polish Club. “Enter HIS Courts With Praise” is carved in the stone over the front door. Who prays in a locked building where everything sacred has been moved out of? Now, it is a Hall of Fame. The words in stone remain. However, today God’s Courts are filled with concertinas, accordions, sheet music for both, a work area to teach how to repair accordions, and a place where famous musicians come to perform—Myron Floren next month. A woman named Helmi owns the Hall of Fame.

Here is other good news, my son and daughter. Your mother will be on local television on the Channel Eight cooking show out of Duluth. Next week’s program, H Is for Hot Dish, features Mrs. Agnes Cieslicki making Baked Noodle Ring. I like it served with hash. We’ll get her a new dress and a trip to the beauty parlor. She’s excited about starring on Channel Eight, as you can imagine. I will drive her over and wait in the TV studio.

Now that I have told you the good, I must notify you of the hydraulics plant cutting back. Your cousin worked in its shop. It was tough for him. We held a benefit supper for Dave at the Club. Your ma and the ladies cooked in the kitchen there. Other women brought bread, cakes, radishes, celery. Dave’s poor health was blamed on the plant. For twenty years, he breathed in the paint fumes. The doctor could do nothing. Your Aunt Cecilia is heartbroken, which is why I write to you in the Big Apple New York and to you, Karen, in Los Angeles, California, to tell you about Ceil Simzek. Here are the teardrops your mother cried for her sister.

More sad news. We have heard of a closing at work, but before I tell you about it, both of you remember: “Laughter is good health.” That is what I do: laugh! I laugh as I sit at the table. I roar as I wait for a phone call, hand too sore to hold the pen I am writing you with. I remember that your mother and I bought you bongo drums when you were in tenth grade, Tadeusz. It makes us happy to think your sister already played the piano. We thought you needed musical training. The bongos lay on the kitchen table for your birthday. These would appeal to you, we thought, but you didn’t like them. You thought you would play the easy way, just tap your index fingers on the drums. The instruction pamphlet said, No, not that way. The proper way to play the instrument was to use the side of the thumb and the little finger of one hand. You’d have to practice to get your wrists loose to play the correct way, so you quit.

Remember when you were watching a rerun of I’ve Got A Secret when I practiced in the kitchen?

“Bring in your new drums,” I said.

“I want to hear what the secret is,” you said.

I ran my fingers down the keys. “Bring in the bongos.”

“For what, Pa?”

You started to close the living-room door on me in the kitchen. I heard Garry Moore, the TV-show star, say, “Enter and sign in, please.”

“Don’t shut that door.”

“I can’t hear the secrets then, Pa.”

“No. At all costs, don’t shut the door.”

With me playing “Hoopi Shoopi,” I know it was hard for you hearing the TV. I didn’t want you to turn it up. That would disturb my practice. I was in my undershirt. I sat at the table I write from now. Accordion to my chest, fingers running over the buttons and keys, I nodded when you came in from the living room to say the show was over. Your mother and you didn’t hear a single secret. “What now?” you said.

“Play a polka with me.”

“I don’t know how. You just got me the drums.”

“Play. Keep the beat up. Ready? One, two, three.”

Tadeusz, beloved son, you looked uncomfortable sitting across the table, drums between your knees. You tapped away. I wanted you to stay with me on “Baby Doll Polka.”

“Play one more song with me,” I said.

“No more,” you said. “I can’t take it.”

Over the years, I’ve tried explaining to you and your sister why I wanted the door left open while I played the accordion. You might have thought it was for air circulation between the rooms, but I didn’t want us—not you, Karen, your friends when they came over—separated by having the door closed on me like that. Those were songs I had played for my dear father. I tried to connect you and Karen to your mother, to your grandfather, to the old country and me, but you were teenagers. How could you connect to anything? “Come hear my songs,” I said.

Karen and you would give no reason for your actions when you left with your friends while I remained at the table practicing the music I cannot allow myself to forget. This is what the accordion means to me, the Scandalli Imperio VII model I had shipped twenty years ago by Greyhound from Chicago to Superior. I have gone to many nursing homes since then. I’ve entertained at Chaffey, St. Francis, Southdale, Beverly Manor. An hour of my music costs the rest homes nothing. I am in great demand and have received letters of appreciation from important social directors. Nobody but your ma, the social directors, and the people in their wheelchairs appreciate what I do.

At the hardboard plant, we have made pressed wood for auto-dashboard trim and for other parts of an auto interior. Ford has shipped our work to Mexico. This is what the accordion and a career of laboring at a hardboard plant have meant to me: I cannot go on without them. The owner of the Hall of Fame told me the white accordion keys are yellow from years of my playing. With acid she can get the keys clean of the discoloration caused by the fingertips. If I throw in the sheet music (most bought from Vitak-Elsnic Publishing Company, Chicago), she will give me three hundred for the accordion. By the way, the Allouez ore dock in Superior could be hurt when Ford closes its St. Paul plant. At the dock, they ship taconite to steel mills on the lower lakes.

Beaten down by such news all the time, but smiling and laughing with your ma, I say, “Agnes, if she calls tonight from the Hall of Fame in the old Presbyterian, I will sell it to her. If no call, I hang on to the accordion forever. Job or no job, I don’t want to let go of it.”

Seven-thirty in the evening has passed. No call from the Hall of Fame. Helmi, the owner, is an ethnomusicologist. “What’s an ethnomusicologist, Helmi?” I asked when I brought the accordion in to see what she would pay me for it. I still don’t understand what is an ethnomusicologist. You and Karen, do you know? Am I, your father, an ethnomusicologist? Helmi has other Vitak-Elsnic sheet music. She has Johnny Picon and Frankie Yankovic records in the Hall of Fame.

Tonight’s cooking show was D Is for Dessert not C Is for Crockpot. I am wrong about the programs. I gave my heart to this accordion and to the job they’ve shipped out of Superior. Next week is your ma’s starring role. “Agnes Cieslicki’s Baked Noodle Ring.”

“Next Thursday. Get ready, Agnes,” I remind her. H Is for Hot Dish.”

“I don’t want you to sell the accordion,” she says. “Why don’t you think about it and have a bowl of stew before bed?”

“Are you crying?” I ask her. “I’m sure no one will call.”

My fingers are sore by this hour of nine o’clock. They are sore as I run my fingertips through her beautiful hair to comfort her. I write this letter as Ma and I talk in the kitchen. She is drying her tears. Tonight’s paper carries other news, “Superior’s Koppers to close for good.”

Koppers Inc. has announced it will permanently close a plant that treats railroad ties with creosote. The facility employed 23 people last winter. Although its ownership had changed over the years, the creosote plant had been in continuous operation since 1928.

(Tadeusz, that is the year the Polish Club began.) Hardboard plant. Creosote plant. Ore dock.

“There is time for bigos,” your mother says. “It will be a celebration. No phone call yet.”

“Okay, I’ll eat,” I say. “Do you feel better about things?”

“For a minute, but there is so much to think about with the hardboard plant, the kids so far off there, and you maybe selling the accordion.”

Son Tadeusz, when Helmi doesn’t call me, I laugh out loud and startle your mother. At the stove, she warms my stew. She looks tired. She wears the housedress you sent for her birthday. No wonder she is worn out, with the TV show coming up next week and everything else. Except for the arthritis, I myself feel pretty good. My accordion case is open on the couch in the living room. There lies the Scandalli Imperio VII. No one will phone me at this late hour.

Your mother’s Treasured Polish Recipes says that, in the old country, bigos is served at every hunting party. The book says a famous writer, Mickiewicz, wrote, “There has been a bear hunt. The bear is killed; a great fire is made. While the bigos is warming in a mighty pot, the hungry hunters drink crystal clear, gold-flecked wodka from Gdansk.” What they did once serves no purpose in Superior.

We have to count more on tourism for our economy, Tadeusz. We have in this city the Old Firehouse and Police Museum, the S.S. Meteor Maritime Museum, and the Accordion Hall of Fame, which the phone book says is called “A World of Accordions Museum.” The museum “houses a unique collection of accordions, concertinas, button boxes and other accordion-family instruments. There is also a library and a gift shop.” Who is going to visit such tourist attractions? Downtown is a mess. You have to be careful the bricks don’t fall on your head when you walk past the Palace Theater and Ansello’s American Grill, but no one is calling about the Scandalli Imperio VII.

“This bigos is excellent,” I tell your mother in order to pick up her spirits. Then I say, “Let the phone ring. After nine-thirty is too late for anyone to call here.”

I do not know what is wrong with her. She can never let a telephone ring without answering it. Here is the worst news. I will say it again: I have lost my job at the hardboard plant.

I think I will play our Polish National Anthem, “Jeszcze Polska Nie Zginela . . . Oh, Our Poland Shall Not Perish While We Live to Love Her.” I will play for both of you so far away on one side of the country or another. I will play it right through the ringing of the telephone. I have said to your mother: “Open all of the doors inside this house, Agnes. Let no door separate me from my house and the house from its music. When you’ve done this, opened all the doors, then I will laugh and play ‘Jeszcze Polska’ with all my strength.”

She opens the storage room in the basement. She opens the doors to the bathroom, living room, and closets up here. She opens the bedroom doors upstairs where we have the second telephone. The phone is ringing. No doors are now closed. Nothing separates the old house from the anthem I play, “Oh, Our Poland Shall Not Perish . . . ” “No, don’t answer it,” I tell her when she is washing the bowl I’ve used and the phone rings once more.

“No,” I would like to tell the companies that send their business elsewhere and hurt Superior. “No,” I would like to say when companies close plants and put us out of work here. “No,” I would like to say to the company that killed Dave Simzek. Instead, I laugh and sing,

Marsz, marsz, Dabrowski

Z ziemi wloskiej do polskiej

I’ll get a severance package from the hardboard plant. Eleven weeks of pay won’t be enough. It will kill your mother and me. And you, Tadeusz, don’t hold it against me. I’d never consider selling the accordion if we didn’t have to worry about things now. I have played the anthem loud so that every room could hear. If we ever sell this house, the Polish anthem will remain in the rooms and closets of every floor.

“Are you crying?” your mother asks when, unable to let it ring, she picks up the telephone.

“Yes,” I say. “I might never play the song again.”

“But it is not Helmi, only your daughter calling from California,” she says. “She is coming on vacation for a week and asks that I make her bigos and that you play ‘Hoopi Shoopi’ for her.”

Leave a Reply