California has suffered two years of drought, and the long-term forecast is for a third. With reservoirs already low, most residential water users have been under severe water restrictions for the last several months. Here in Thousand Oaks, we are expected to reduce our water use by 50 percent. Outdoor watering is restricted to one day a week and limited to no more than 10 minutes per irrigation area. The watering cannot be during daylight hours, and sprinklers cannot be used. Washing vehicles, spraying off patios or driveways, and filling swimming pools are prohibited. Water meters are electronically monitored, and there is a 24/7 water patrol. Violators are punished by fines of up to $500 per incident, and repeat violations will result in the placement of a flow restrictor on one’s water meter.

at the 2019 Democratic Party State

Convention (Gage Skidmore /

CC BY-SA 2.0, via flickr)

Governor Gavin Newsom and other elected officials in Sacramento have blamed our water problem not on their lack of action to develop new water resources but on “climate change.” Actually, most of California is semi-arid, and droughts, as tree rings indicate, have been occurring for thousands of years. Franciscan priests at the California missions were noting droughts in the 1770s and 1780s, and so, too, were the first American settlers in the 1830s and 1840s.

Moreover, the bulk of California’s precipitation—snow in the mountains and rain in the lowlands—typically falls from late October to late March, and the rest of the year is mostly dry. This means that in both drought years and high-precipitation years, water must be captured and stored during the wet months for use during the dry months. Throughout the 20th century, California was doing just that—building dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts at a rate to keep pace with California’s growing population and increasing agricultural and industrial production.

However, during the last couple of decades, as California has become ever more a one-party state, the Democrat super-majority has not only failed to develop new water resources but has also not properly maintained California’s already existing infrastructure of dams, reservoirs, canals, pipelines, and aqueducts. The failure of the Oroville Dam’s main and emergency spillways during heavy rains in February 2017, causing the evacuation of nearly 190,000 people, is but one of several examples of the state’s woeful negligence in maintaining critical infrastructure.

From the time Los Angeles was settled in 1781 until the early 1900s, the town relied on the less-than-mighty Los Angeles River to supply its water needs. Since the population was only in the hundreds or low thousands until the 1870s, the river was entirely adequate. However, the population grew to 11,000 by 1880, then exploded to 50,000 by 1890, and doubled to 100,000 by 1900. The river, at that point, was being sucked dry. An increasing number of wells were dug during the 1880s and 1890s, and the water table dropped precipitously. Then, the season of 1903-04 brought only eight inches of rain to Los Angeles, and it appeared that the bottom had dropped out of the river.

City leaders understood that droughts were part of life in California and developed a plan to import water from afar. Former Mayor Fred Eaton proposed tapping into the Owens River, which drains the eastern Sierra Nevada. He consulted with William Mulholland, a young Irish immigrant who had worked his way up in the city’s water department from ditch digger to chief engineer. Familiar with the land between the Owens Valley and Los Angeles, Mulholland soon had a plan for a 250-mile-long aqueduct. Nothing like it had been done before in the United States, but Mulholland reckoned that if the ancient Romans could build long-distance aqueducts, so could we. Desperate for water and convinced of the feasibility of Mulholland’s plan, the citizens of Los Angeles voted overwhelmingly for bond issues totaling nearly $25 million to finance the project.

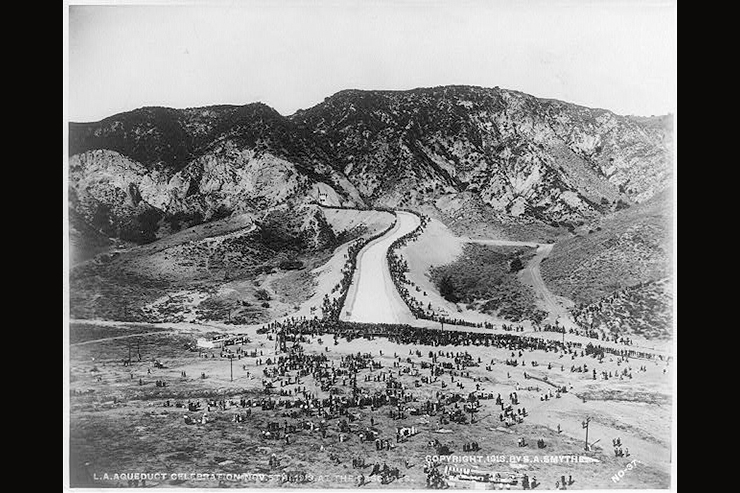

Mulholland completed the aqueduct and the series of dams, reservoirs, and tunnels in 1913, on time and under budget, a stunning contrast to project performance in California today. A crowd of 40,000 watched as the aqueduct’s water gate was opened on a hill above the San Fernando Reservoir and water came cascading down a concrete channel into it. “There it is. Take it!” exclaimed Mulholland.

Los Angeles residents took not only the water but also the electricity generated by hydroelectric plants along the aqueduct’s route. The population of Los Angeles had tripled while Mulholland was building the aqueduct and would reach 575,000 by 1920 and 1.2 million by 1930. This incredible growth caused Mulholland to think about tapping into the Colorado River.

By the mid-1920s, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power personnel were in the field surveying potential routes for an aqueduct, causing six Colorado River Basin states—Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico—to form a coalition to fight Los Angeles. The city responded by creating the Metropolitan Water District, a coalition of more than a hundred towns in six different counties, covering an area of 5,000 square miles. The fight for the water of the Colorado River was ended in 1928, when Congress passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act, providing for the building of Boulder Dam and the division of the river’s water amongst California and the other states.

The building of the Colorado River Aqueduct was financed by a $220 million bond issue approved by voters late in 1931. Construction began in 1933 and was completed to the distribution point, Lake Mathews in Riverside County, in 1939. It would take another two years to complete all the distribution lines before starting a flow of up to a billion gallons of water a day.

Without that water, the continued growth of Los Angeles and Southern California in general would have been impossible. It came just in time for WWII and the plants of Douglas, Hughes, Northrop, Lockheed, Consolidated, and North American and their more than a half million workers to build over 200,000 planes during the war.

Although San Francisco receives nearly double the average seasonal rainfall of Los Angeles, the precipitation, like that everywhere in California, varies greatly from year to year. By the late 1890s, Mayor James Phelan and other city leaders realized that for San Francisco to continue to grow and prosper, it would need to import water. Phelan proposed damming the Tuolumne River in the Sierra’s Hetch Hetchy Valley and building an aqueduct to transport the water to San Francisco. Phelan’s proposal was popular in the city by the bay, but the idea faced opposition elsewhere because Hetch Hetchy Valley was part of Yosemite National Park.

The battle over Hetch Hetchy continued until 1913, when Congress passed the Raker Act, which allowed damming the Tuolumne and flooding the valley. In 1914, work on the Hetch Hetchy Project began. In charge of the project was Michael O’Shaughnessy, an Irish immigrant like William Mulholland, but, unlike the self-taught Mulholland, O’Shaughnessy was a university-trained engineer. By the time of the project, he was already a prominent figure in San Francisco for the many tunnels and rail lines he had built in the city and for several rail lines he had constructed elsewhere in California.

San Franciscans enthusiastically passed several bond issues—eventually totaling $100 million—to finance it. By 1919, O’Shaughnessy had built a narrow-gauge railway to carry workers, supplies, and machinery 68 miles from the Sacramento Valley to the mouth of Hetch Hetchy. By 1923, he had finished the O’Shaughnessy Dam, and by 1925, the first of three powerhouses. A 156-mile aqueduct, which included 85 miles of tunnels, and the other two powerhouses were completed by 1934.

The State of California got into the water business when it passed the Central Valley Project Act in 1933. The Great Depression made financing difficult, and years of wrangling with the federal government ensued until the late 1930s, when California, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Army Corps of Engineers launched a joint effort. The project took 30 years to complete and involved the building of numerous dams, reservoirs, canals, and powerplants to transfer the water from the far north of California, which receives abundant precipitation, to water-deficient but highly fertile areas of the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys.

Begun in 1961 and completed in the 1973, California’s State Water Project included building Oroville Dam on the Feather River in the northern Sierras and a series of dams, reservoirs, pipelines, pumping stations, and the California Aqueduct, which carries 70 percent of the water to Southern California and distributes the rest to the Bay Area and the central coast.

When the State Water Project was completed, California’s population was around 20 million. Today it’s 40 million, yet we have had no new water projects in the intervening years, and we have failed to properly maintain the systems already in place.

In a state with 840 miles of coastline, an obvious answer to California’s water problems are desalination plants. Nonetheless, there is now but one large-scale desalination operation on the entire coast, the privately funded and operated Poseidon Water facility at Carlsbad. The plant supplies San Diego County residents with 50 million gallons of water a day, enough for 400,000 people. We should have two dozen such large-scale plants in operation, but getting the California Coastal Commission to approve the permits to build them is nigh impossible. The commission’s 12 voting members—all appointed by Democrats—recently voted unanimously to deny Poseidon a permit for a desalination plant in Huntington Beach.

California has been living off its legacy of water projects for the last several decades like a lazy, self-indulgent, trust-fund recipient. Our current water problems are not the consequence of so-called climate change or even of our current drought—just one of many in the last 250 years of recorded history in California—but of a crisis in leadership.

Leave a Reply