One of many reasons conservatives are so often at a disadvantage in political discussions is that we do not see why there should be any discussion, since we do not recognize a problem open to discussion at all.

Take, for instance, assimilation. If you do not believe the United States should be accepting immigrants in the first place—and I mean, at this point in history, any immigrants at all—then the issue of whether immigrants should be made to assimilate is, at the very least, a secondary question, since your main concern is for halting immigration entirely.

The issue here is, among other things, whether solutions to the assimilation problem should be developed at the national level or the local one. Under the U.S. Constitution, the establishment of “a uniform rule of Naturalization” is entrusted to the federal government, not to the states that make up the federal union. The Constitution, however, is mum on the subject of any kind of rule, uniform or not, of assimilation; the Constitutional Convention never envisioned the central government needing to have a policy. This, of course, is because sedition, not assimilation, was what the new government believed it had to fear from uncooperative and malign aliens.

That is not to say that the Founding Fathers, as individual citizens, were unconcerned by nonassimilation—quite the opposite, in fact. John Jay, John Adams, John Randolph of Roanoke, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington—to name just a few—all spoke or wrote on the importance of what they called uniformity of principles and habit and the necessity for a heterogeneous compound formed by one American people.

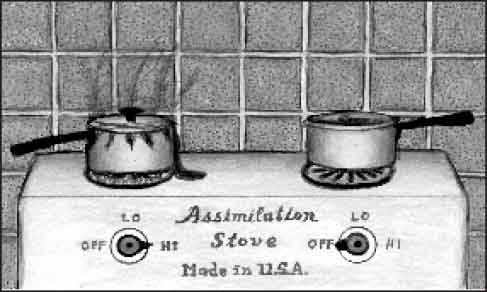

While the U.S. government passed, in 1819, the first federal act dealing with immigration and, a year later, went on to enact what became a national immigration policy, before 1819 and after that time, the various states and municipalities wrote and enforced their own immigration controls. Nevertheless, for about 150 years now, immigration policy has been the preserve of the federal government and is certain to remain so. Moreover, no assimilation policy whatsoever exists. We may be absolutely certain, however—particularly after September 11—that if such a policy ever is created, it will be a federal policy with an agency or subagency of its own, managed by Bill Bennett, Lynn Cheney, John Miller, Ron Unz, or one or another of their faceless simulacra. So enough said about assimilation as a national project, like the WPA, CCC, VISTA, or AmeriCorps. The real issue is immigration.

Despite the impression readers may have received from The Hundredth Meridian, I cannot claim to have traveled extensively in Mexico. I have spent enough time south of the border to have developed plenty of impressions of Mexico and the Mexican people and to have drawn what I consider to be fair conclusions.

Mexicans in Mexico are a warm and friendly people, even to gringos—particularly when the gringo wears jeans, cowboy boots, and a straw hat instead of shorts, a Hawaiian shirt, and a Como Caca cap. Much of the tension between the Mexican natives and tourists is class-based and unrelated to racial or cultural differences. Mexicans are a simple, not to say naive, people, accustomed to accepting others at face value. This partly explains why Mexican culture seems primitive to American and European visitors—who are charmed or appalled, accordingly—when, in fact, it is simply basic. This quality of basicality, so repellent to the ordinary tourist, has fascinated artists and writers—Caroline Gordon, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Malcolm Lowry, Tom Lea, Cormac McCarthy—who discover in it reality, la condition humaine, which is, of course, what genuine artists and writers are after. This reality is what I value and appreciate in Mexico, to the extent that it no longer exists in the United States.

I find attending Mass in Mexico, where often the church floor is dirt and the congregation is made up of people in rags, the halt, and the lame, a far more genuine and moving experience than attending Mass often is in the United States, where half the affluent so-called worshipers are in shorts and sandals and the kid in front of me is wearing a T-shirt with a drawing of one pig mounting another on the back of it, above the legend “Makin’ Bacon”—precisely obscuring my line of vision just at the moment of the elevation of the Host.

If immigrants from Mexico brought that quality of simple piety and basic experience north with them, I would feel somewhat better about the invasion from Mexico—while uttering a prayer that Makin’ Bacon and his sort never make their way south to Chihuahua, Sonora, Jalisco, Zacateca, and Sinaloa to poison the forms of local piety there. They do not bring such piety north, of course, because it is precisely that simplicity of experience that immigrants to the United States are attempting to escape. Far from appreciating the human condition for what it is, they hope to transcend it; and, while we cannot entirely blame them for that, we need to realize that the immigrant “dream” we hear so much about from American politicians, journalists, and immigration activists is essentially a proletarian dream, a dream that has a very specific cultural and political component. If there is anything worse than proletarians, it is proletarians with money; and America is rapidly becoming a nation of such proletarians.

Since the 1920’s, America has been a proletarian’s dream, which is why she has become a magnet for the proletariat internationally. Native-born Americans have devolved from a free and independent people into a wealthy proletariat—which is not a contradiction in terms when you think of how servile politically, how puerile and degenerate culturally, we have allowed ourselves to become. What is most attractive about America for today’s immigrants is precisely what sophisticated and intelligent Old Americans abhor most about their country: shopping malls and fast food, slovenly clothing, movies, TV, rock music, mass sports events—in other words, bread and circuses.

It is not that Americans are assimilating to the immigrants; instead, both are meeting halfway to form the North American component of an international proletariat that happens to be American in the same way that U.S.-based international corporations happen to be American. In other words, both natives and immigrants are assimilating to an international ideal—one that is created, fostered, and developed by globalist financiers, corporatists, and politicians alike—inspired by the American example. Immigration, viewed in this way, is quite literally the fusion and reinforcement of the worst of both worlds, the Third and the First.

Those simple, open, warm Indians—and we need to remember that, when we speak of Mexicans, we really mean Indians working for the Indian, not the Spanish, reconquista—I know from riding the third-class trains in Mexico, attending the bullfights there, walking the streets, and eating and drinking in the restaurants and cantinas, become a very different people when they cross the border to settle in El Norte. Partly, this is just human nature, whose hostile, competitive, and exclusivist side is always encouraged by the presence of its own kind in numbers. Increasingly, however, it is assuming a deliberate political aspect, developed and encouraged by politicians in Mexico City determined to established a powerful Fifth Column in the United States. Whether the aim ultimately is reconquista does not really matter. In fact, I can imagine that Washington, say a half-century from now, will be delighted to give Texas and California back to Mexico (if she wants them back, that is). Why buy the cow when you can get milk through the fence?

And it is not just Mexican immigrants who are getting aggressive. “Spokesmen” for the Asian immigrant community are beginning to follow the Mexicans’ example. My late friend Jim Rauen, who spent his life in Chicago before he retired to New Mexico, told me a story about a Korean couple who owned the condominium next door to his on the Gold Coast. “You know,” the Korean wife told Jim, “we think you and Ann should know how Koreans feel about white people. We think you’re lazy and you’re stupid and you’re ugly, and also you smell. We Koreans expect to take over America and run it for ourselves. No offense, you understand. Just so you do understand.” (If it had been I instead of Jim, the only honest Korean immigrant in America would have been a dead Korean immigrant as well.)

An implicit theme of my book, The Immigration Mystique, is that, contrary to received opinion among even immigration restrictionists and reformists, the post-1965 immigrant groups are not the only ones who have not assimilated. The post-Civil War immigrants—the Irish to some extent, the Slavs, the Southern Europeans, and those from Eastern Europe—have not, either. Needless to say, this was among the least popular arguments in a very unpopular book, and I have regretted ever since that I neglected to appeal to Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s and Nathan Glazer’s Beyond the Melting Pot as well as Michael Novak’s Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics for support. All three men made the same argument that I did, while staying rich, famous, and respected into the bargain, being obviously non-WASP. I could not get away with saying the same thing, of course. (With a name like Chilton Williamson, Jr., no one suspects you of being Catholic.)

For most of America’s history—up until 1965, that is—the dominant WASP population was resented and disliked by non-Protestant, non-British immigrant groups. Since 1965, that dislike and jealous resentment has been transferred to European-Americans generally by non-European immigrants, encouraged by a natural sense of ethnic and cultural hostility and identity as well as by the suicidal impulses of European-America itself. Today, the only conceivable advocate for assimilation is the federal government, for whom assimilation only amounts to another form of “homeland security.” And we may easily imagine what a national crusade for assimilation in that context would entail.

So it comes down, finally, to this: If there is no need for something, there is everything to be said against having it, and nothing to be said for. Does America really need 30 million foreign-born proles arriving over a period of three decades to complement the 200 million native ones already here? Whether assimilated or not, more immigrants spell nothing but inconvenience, at best, and disaster, at worst, for this country.

Leave a Reply