The end of my love affair with sports.

A saner man would have seen, long before I did, the subtle signs that his love affair was on the ropes. Perhaps I did not want to see it. But in my defense, I would start by saying that it is difficult to overstate the influence sports can have on the average American adolescent boy, and such sway is difficult to shake, even years later.

I fondly recall the care with which my best friend and I handled our collection of baseball cards, and the genuine and meticulous contemplation taken in trading them with each other. My adult self looks back with nostalgia at the simpler time when trading a Tom Seaver for a Carlton Fisk was a negotiation of extreme magnitude. In adulthood, I grew puzzled by the idea of owning an object signed by a famous person, but between the ages of seven and thirteen, I may have taken a Dale Murphy or Pete Rose autograph over a million dollars if given the choice.

These were the days before the internet. Even the video games we indulged in were primitive and usually of the sports variety. In the living room of my parents’ home, I kept a plastic baseball bat to use while imitating the various stances of the hitters I watched on television. My friends and I would transform our front yards into the diamonds of the majors and play out our fantasies on hot summer days in the dirt, dust, and grass. Our rooftops became stands filled with throngs of captivated fans.

Eighty miles to our east was the city of Atlanta. I remember the smell of popcorn and peanuts the first time I entered Fulton County Stadium, the home of the Braves, at the age of seven. I soaked in the enormity of the park, the diminutive size of the players from our view in the cheap seats, the crack of the bat, the (delayed) pop of the ball hitting a leather glove, the amplified voice of the announcer, and the loud declarations of “cold beer” coming from the usher making his way through the mass of people.

I am grateful not only for the details I recall but for those that were blissfully absent. I never once remember national politics being a part of the experience. The idea of caring what the first baseman thought about the minimum wage would have been regarded as bizarre and silly.

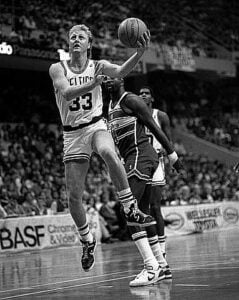

In basketball, it was Larry Bird and the Boston Celtics of the 1980s that fueled my fire. With the possible exception of “Pistol” Pete Maravich, I had never seen anyone handle a basketball like Bird. He could do it all—scoring, assists, rebounds, leadership—and I think his 1986 Celtics team was one of the best in the history of the game.

(Steven Carter / via Wikimedia

Commons, CC BY SA 2.0)

My bedroom was covered with posters of sports superstars, one of which featured Bird suspended in air, body horizontal to the floor, hand outstretched, reaching toward a ball near the foul line. The caption was his own words: “It makes me sick to see a guy just watching it go out of bounds.” Bird played with a reckless abandon that undoubtedly shortened his career, but he knew no other way. By the early 1990s, the Celtics were no longer winning championships, and in the twilight of his career, Bird spent portions of games lying on the floor of the sideline, trying to relieve the intense pain gripping his back so that he could reenter the contest. It was watching this ailing and aging version of my basketball hero that led me to yet a new admiration for the competitor in him. This Bird rose even higher in my mind than the one of buzzer-beating baskets and MVP awards.

When I was nine, my dad poured a slab of concrete underneath my basketball hoop in the back yard. Using stencils and spray paint, we emblazoned the last names of Celtic greats along with the years of their championships, and we christened the place “The Boston Garden.” In pickup games with friends, I defended my “home court” like I knew Bird, McHale, Parrish and DJ would have done.

But neither baseball nor basketball matched the passion I developed for University of Alabama football. The oppressive heat and humidity of a Deep South late summer transitioned into the crisp air and falling leaves of autumn as season after season unfolded on the gridirons of Legion Field in Birmingham and Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa, where my crimson-crowned warriors battled their (our) foes.

What makes grown men, many with children and grandchildren older than the participants, wrap their weekend happiness around the ability of young men to put a ball in a hoop or a piece of pigskin in an end zone?

College football invokes a special passion in the South. My theory is that the intensity springs from the unpleasantness of the 19th-century Yankee invasion. Football is the closest thing we have to domestic martial combat these days. Fans and alumni develop a close association with—and pride in—their schools and their states. This battlefield phenomenon has been our vicarious opportunity to strap on some gear and kick some ass. Throughout the turmoil and controversies of the 1960s, with Alabama and her sister states being the perennial whipping boys of the national elites, we held our own, and then some, on the football fields. Numerous and dubious studies and surveys found us last in all kinds of categories, but stopping us from being atop the football polls proved a much more difficult task.

I am barely old enough to remember the final days of the great coach Paul “Bear” Bryant stalking the sidelines and leaning against the goal posts, his haggard eyes squinting beneath his houndstooth hat. In those days, one could find in many an Alabama home two men displayed in framed portraits, each holding prominent places: Jesus Christ and Bear Bryant.

I transitioned from childhood to adulthood closely following the array of post-Bryant coaches trying to succeed in his shadow. For a quarter century, no one could match the legacy he left at the Capstone … until Nick Saban took the helm in January 2007 and built a powerhouse that would win six national championships, to date.

Surely there is a psychological treasure trove to explore on the maturation of the avid college sports fan. As boys, we looked up to these athletes. As young adults, we likely saw them as gifted and heroic peers. But what makes grown men, many with children and grandchildren older than the participants, wrap their weekend happiness around the ability of young men to put a ball in a hoop or a piece of pigskin in an end zone?

For me, and many like me, it was not so much about the players themselves as it was about their role as competitors who were representing our school and our home state. But in an age of constant media, there is now unprecedented access to the players and their personal lives. Because of that, I began to learn more about these young men who purportedly carried the same banner I did. My fairy tale was exposed. For the most part, they were nothing like me. More than ever, they hailed from outside the South. They knew nothing of the school’s history and did not care to know. They did not share the same music. They did not share a love of Southern heritage. They did not worship my God.

Nick Saban’s net worth is in the neighborhood of $60 million and soaring. With incentives, he makes about $10 million annually as head coach of the University of Alabama. He tacks on hundreds of thousands more through endorsements, television commercials, regular speaking engagements, and various other promotions.

For years, Saban has publicly bemoaned fans who leave blowout games early. I find this amusing. Nick lives in another world, completely oblivious to the average member of the fan base that adores him. He arrogantly chides blue-collar people who pay exorbitant amounts for game tickets and refreshments, but we can rest assured that he never waits in a line and has no concept of getting home in the wee hours of a Sunday morning after being stuck in Tuscaloosa traffic jams.

In Thanksgiving week of 2016, I was listening to Saban’s weekly “Hey Coach” radio broadcast, which takes call-in questions from fans. One caller that night simply asked Nick what he was thankful for. Saban gave a response that touched on his players, his wife, and the opportunities he had been given in the game of football. There was not a word about God, He who makes all opportunities possible and is the author of all our blessings. How sad, I thought. Here is a man of such talent, arguably the greatest college football coach in history, and the most recognizable man in the State of Alabama. He has been given such an influential and far-reaching platform, yet to this day, in all the multitudinous times I have heard him speak, I cannot recall Saban’s ever having given a meaningful comment regarding his Creator.

Then came Social Justice Summer 2020, characterized by mass “woke” pandering, heritage destruction, and false narratives. Saint Nick climbed aboard the train. First, he filmed a commercial with a select group of players who declared, “All lives can’t matter until Black Lives Matter.”

Then came the pivotal moment. On Aug. 31 of that summer, Saban led a group on a march down Paul Bryant Drive. Included in the crowd were several people sporting social-justice paraphernalia. One large black male wore a t-shirt reading, “God Looks Like Me.” One carried a sign with the black-power fist. The terrorist Black Lives Matter flag was unfurled. Saban was later quoted as saying, “I’m proud of our messengers over here, and I’m very proud of the message.”

The crowd marched to Foster Auditorium, and Saban stood in the schoolhouse door where Governor George Wallace had stood in 1963 and delivered a social-justice speech that left ESPN’s Kirk Herbstreit shedding crocodile tears.

Why did Saban do it? Does he really believe in the woke agenda? Extremely doubtful. More likely, he seized on the issue of the day as an opportunity to better his standing among his most talented players and among future recruits. He must have calculated that such an action carried little risk of alienating a fan base so in love with him that they would put their own feelings aside as long as he kept winning championships. If that was Saban’s line of thought, he acted shrewdly. His risk paid off: the five-star recruits keep pouring in, and his popularity is as high as ever.

Well, not with me. I believe that the sanctity of truth and justice should not be compromised for the sake of winning ball games. Southern heritage is too precious to me for my support to be extended to those who would tarnish and degrade it.

On May 13, 1914, the Alabama division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed a large stone memorial in the heart of the University of Alabama campus, on the quad in front of Gorgas Library. On the stone was a plaque commemorating the soldiers whom the university gave to the Confederate cause. In particular, honor was bestowed on “the Cadet Corps, composed wholly of boys” who went to face the invading Union army on April 3, 1865, in a vain attempt to protect their school. The veteran Union opposition succeeded in burning the campus to the ground the following day.

In my days as a student there, I was a part of various ceremonies and events coordinated around that stone. I led prayers beside it. In ensuing years, my attendance at games traditionally involved a stopover at the stone to pay my respects to my young predecessors, who, in contrast to the chowderheaded, pissant protestors of today, knew what true sacrifice meant. I keep an esteemed picture of my two sons posing beside the stone in 2012.

There will be no more such moments of courtesy or photos. Just prior to Saban’s woke commercial and march, the university began tearing down Confederate memorials across campus. A large crane was brought in to extrude the stone from the ground where it had stood for over a hundred years. The memorial to those brave boys became another of the numerous sacrifices made on the altar to the 21st-century post-Marxist left.

I have learned that God may remove idols from His people by simply taking the idols away. But He also may choose to accomplish the same effect by changing our disposition to such a degree that the idols lose their allure.

So it was, deep in the blues of September 2020, that I realized my mistress and I were no longer compatible. I felt like Old Blue Eyes sitting at the bar where he laments the end of his love affair. We had a good run. Had my mistress changed? Or did it just take the public mocking to make me see her for what she really was? Either way, it was over. It had to end. As Frank told bartender Joe, this was a torch that had to be drowned.

Top image: The University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban leads his team on a march in support of Black Lives Matter on Aug. 31, 2020 in Tuscaloosa, Ala. (Vasha Hunt / Associated Press)

Leave a Reply