Back in April, my old friend D.B. “Dukie” Kitchens called to inform me that I should soon expect in the mail an invitation to the inaugural Patriot Book Awards ceremony, to be held in Atlanta in late May. “What did I do to deserve this honor?” I asked.

“Nothing,” Dukie replied. “I got your name on the press list. It’s an all-expenses-paid, booze-provided weekend, with gorgeous book-rep babes galore, and your old pal, moi, to guide you through the publishing underworld.”

I protested that I really had no interest in book awards, since nothing I cared to read had won an award for decades. Besides, I said, “Atlanta makes me break out in existential hives.”

But Dukie was insistent. This is not your ordinary book award, he said. “This is a conservative books award.”

“Conservative!” I chortled. “What does that mean? Are the nominations certified by some Tea Party focus group?”

“Not quite,” said he, “but if you’d occasionally pull your Luddite nose out of the Dark Ages, you’d know all about this. FOX News has been pumping it up for weeks.”

The offer began to sound tempting. I hadn’t been out of the Lowcountry for a coon’s age; a bourbon-drenched weekend in a posh hotel might be just the thing.

Several weeks later, as I motored out of Charleston on a Friday morning, I reflected on what I had learned about the Patriot Awards: a conservative response to the liberal dominance of the American literary scene and its signature prizes—the Pulitzer, the National Book Award, et al. The Patriot was being touted by conservative pundits as more genuinely representative of the wholesome common sense and good taste of the American people—not just a cabal of New York publishers, writers, literary critics, and soi-disant guardians of high culture. As a move in the public-relations game, this was savvy enough. After all, the populist appeal to American “common sense” has a long history, and any suggestion that the literary “taste” of the average American might be mediocre at best is bound to invite indignant charges of elitism. According to the Patriot Awards website, the prizes in five categories (fiction, poetry, autobiography, biography, and nonfiction) would be awarded democratically. The usual panel of “literary experts” would be eschewed. Publishers would nominate one book in each category, and those books would be sent to representative groups of readers. The awards’ sponsor, the somewhat sinister-sounding Committee for the (Re)Occupation of Middle America (COMA), would select readers proportionately from every class, ethnicity, and sexual orientation, as well as from a broad variety of occupational and educational backgrounds. To ensure that everything remained objective, a third-party (the NSA) would oversee the process, maintain secrecy, and tabulate the results after readers ranked the nominated titles.

As I entered the ever-mushrooming outskirts of Atlanta, I puzzled over why this flashy icon of the New South had been chosen as the locale for the Patriot Awards. If Nashville is the Buckle on the Bible Belt, then Atlanta might aptly be called the Rhinestone in its Belly Button—assuming, of course, that the belly is hanging well below the buckle. But perhaps I am being unfair. Maybe we were to imagine the Patriot Awards as a symbolic rising out of the ashes, the beginning of a renaissance in American letters. Improbable, yes, but who knows? I resolved to stifle my cynicism—with a little help from Jack Daniels. That resolve was soon rewarded as I checked into my room at the Marriott Buckhead, where the ceremony was to be held, and found it well stocked. Half past three was a bit early to imbibe, but what the hell, I thought, and, as I gazed out my window upon the high-tech sprawl of Hotlanta, I lifted my shot glass in a silent toast to General Sherman, who had made it all possible.

My reveries were soon interrupted by an annoying buzz in my pocket—a text message from Dukie: “in the lounge. lets shake and bake, mr pibb.” Dukie and I go way back, so far back that I can’t even remember when he first started calling me Mr. Pibb. We spent many a summer evening mullet fishing in the backwaters of Mobile Bay and roomed together as undergrads. He’s one of the best investigative journalists in the country and, despite his many faults, a loyal friend. I threw on a blazer and made for the lounge.

I should have known that Dukie wouldn’t be alone. He was seated at the bar wearing the same old grin, and next to him perched a raven-haired young thing who might have passed for 21. I learned that her name was Kaylie, which didn’t quite match her look: black boots, black jeans, and a tight black T-shirt, upon which was embossed the face of Ayn Rand in a style curiously resembling those ubiquitous images of Che Guevara in his jaunty red beret. “Pleased to meet you,” I said, seating myself atop a plush barstool, while a shot of Jack appeared mysteriously in front of me. Kaylie offered a smile that might just as well have been a sneer. Maybe it was the three piercings in her lower lip and the one in her right nostril that gave me that impression.

“Kaylie’s a journalism major at Emory,” Dukie informed me with a wink. Dukie had been living in Atlanta for several years, and occasionally taught classes in the evenings to make ends meet, so I took his wink to mean that Kaylie was a student of his. In any event it was clear that she resented my intrusion and responded to my inquiries about her career plans in clipped monosyllables. Dukie seemed to find her rudeness enormously amusing.

As the lounge began to fill with happy-hour drinkers, most of them conspicuously overcoiffed, I was reminded of a Republican campaign rally I’d attended last year. Hoping to direct Dukie’s attention to the job at hand, I asked, “Are most of these people here for the awards?”

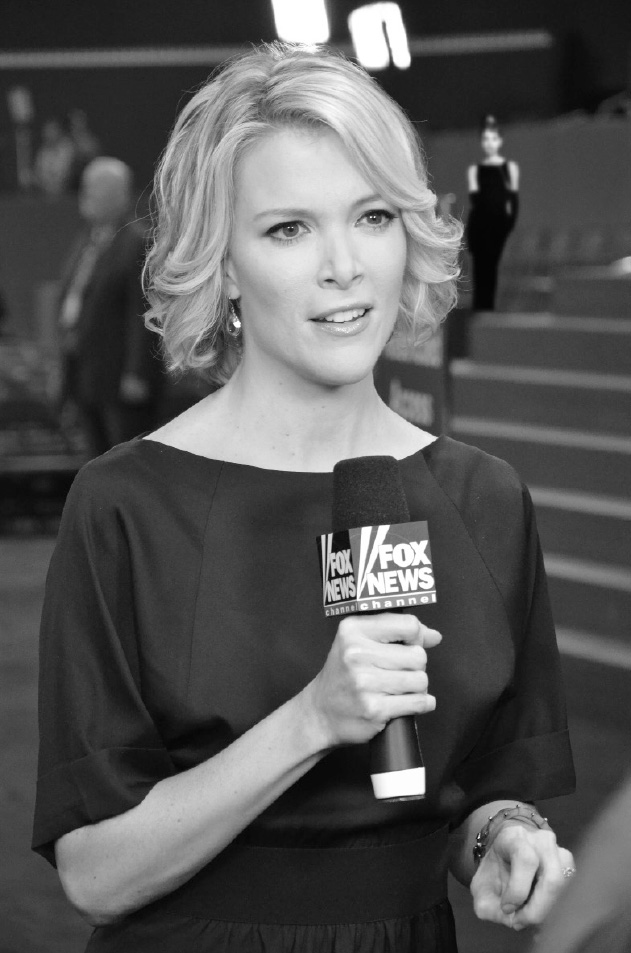

Gazing into the mirror behind the bar he replied, “Oh, yes. That’s Megyn Kelly, the FOX News anchor, over there at the window table.” Turning, I saw a tallish blonde surrounded by a gaggle of baby-faced 20-something males.

“Does she know anything about books?” I asked.

Dukie put on that exasperated look I knew so well. “She was a corporate litigator before she became a news babe. Those people don’t read books. But she’s eye candy, Mr. Pibb, and she pulls an audience—a very big audience.” I wondered aloud whether Kelly was to be the MC at the main event on Saturday evening.

“Oh, no,” Dukie intoned. “The COMA wanted a little more . . . gravitas for their money. Pat Sajak got the nod.”

As we moved from the lounge to the Marriott dining room I mulled over the significance of using a popular game-show host as the MC at a literary event. Dukie explained what I should have known: that Sajak had been an advocate of conservative causes for years, sat on the board of trustees for Hillsdale College, and, most importantly, was one of the directors of Eagle Publishing. Eagle, of course, is the parent company of Regnery/Gateway, as well as the publisher of Human Events and RedState.com, not to mention owner of the Conservative Book Club. As we made short work of our filet mignon, Dukie surveyed the dining room. “Perhaps you haven’t noticed Mary Matalin over there; former campaign director for Dubya, now executive editor at Threshold Editions, publisher of Dick Cheney’s immortal In My Time. Threshold, of course, is the conservative Simon & Schuster imprint.” He paused. “Or cast your eyes in the other direction, Mr. Pibb. See the lady in red? That’s Dana Perino, former Bush White House press secretary, sometime FOX News commentator, now executive editor at Crown Forum, the conservative imprint at Random House.”

“It all seems,” I commented, “a bit incestuous.” But Dukie’s point wasn’t really about politics. Book awards, he insisted, had always been about selling books, not about promoting good literature. The National Book Award, for instance, was established in 1936 by the American Booksellers Association. The Patriot Awards were heavily backed by conservative booksellers and had close ties to conservative news media, and all these people are adept at targeting their market. In this case the market is an estimated 50 million-plus potential readers whose politics tend to be socially conservative. Crown Forum may be the embarrassing stepchild in the Crown Publishing family, but Random House executives chuckle all the way to the bank.

After Dukie promised to meet me for breakfast the next morning, I returned unsteadily to my room and contemplated the state of American literature in 2013. Very few American publishers of any size are now independent; most are owned by conglomerates, and few are prepared to take risks on books that don’t promise to sell hundreds of thousands of copies on the first print run. Novelists, for example, who aspire to write for serious adult readers are out of luck. Consider USA Today’s top one-hundred sellers of the last 20 years. Seven out of the top ten are titles by J.K. Rowling. Stephanie Meyer and Dan Brown pop up with some regularity further down the list. To find a novel that might be worthy of being read generations hence, you must scan down to No. 22, To Kill a Mockingbird, written over 50 years ago! Aside from reprints like Mockingbird and Catcher in the Rye, there is nothing in the top 100 that anyone in the year 2113 will care to read, assuming that by then literate Americans have not been placed on the endangered species list. Paradoxically, as the number of Americans who might be thought serious readers continues to diminish, the number of literary prizes on offer has risen absurdly. Wikipedia lists 223 of them in the United States. Have you heard of the Lulu Blooker Prize? That’s for “books based on blogs.” How about the Native Writers Circle of the Americas awards? In short, one need not be unduly cynical to assume that the indecent proliferation of prizes is an index of the publishers’ desperate desire to find or create new markets for their wares.

I found Dukie alone in the dining room on Saturday morning, nursing his second Bloody Mary. “Where’s your punkette?” I asked.

“Who knows?” growled Dukie. “She’ll turn up this evening, I’m sure.”

I thought to inquire, “What are her politics? I couldn’t help but notice the Ayn Rand T-shirt.”

Dukie grunted. “She calls herself an “anarcho-libertarian.” He sat in silence for a while, then abruptly seemed to recall our conversation of the evening before: “All of these award ceremonies are ‘pseudo-events’ anymore. Everything is calculated for media impact. The only thing that matters is that the ceremonies get noticed. Any publicity is good publicity. Scandal is best of all.”

“Is something scandalous likely to happen at tonight’s ceremony?” I wondered.

“We’ll see,” Dukie said. “Let’s stroll over to the exhibition area and check out the book-rep babes.” The exhibition was held in one of the Marriott’s smaller ballrooms, where dozens of tables had been set up by publishers who had either nominated books for the awards or were simply displaying their recent titles. The place was crawling with book buyers for the big chains.

Frankly, it was hard to pay much attention to the books when the reps were so much more attractively packaged. “Damn,” I said, “I’ve seen one or two sexy book reps in my day, but these girls look more like a cheerleading squad.”

Dukie smiled. “You hit the nail on the head, Mr. Pibb. These girls are all Falcons cheerleaders, but don’t ask ’cause they won’t tell.”

I was nonplussed. “You mean the COMA hired these girls just for the event?”

“Exactly,” said Dukie. “They’ve probably all memorized a little spiel to promote the books.” Indeed, but with all that cleavage on display they really didn’t need to say anything at all. Dukie and I happily walked through the aisles of booths, ogling the titles. Sue Monk Kidd’s latest, Dancing With Mystical Bees, seemed to be garnering a nice crowd. Stephen King’s autobiography, My Life as a Literary Shock Jock, was attracting notice, especially since an Amazonian blonde in bloody red stilettos was handing out review copies to the press. Over at the Little-Brown booth stacks of Malcolm Gladwell’s The Sacred Chao were prominently displayed, but the most interesting were, naturally, the political selections. Virtually all of them bore conservative imprints. At the Crown Forum table, Charles Krauthammer’s How the War on Terror Builds American Character was the center of a small frenzy. Just across the aisle, at Threshold Editions, Marco Rubio’s Brown Like Me was being touted as the sequel to his recent memoir, An American Son.

“Is this a joke?” I asked Dukie.

“Not at all,” he replied. “The senator argues that legal immigration from Latin American, especially women, should be tripled. He claims that not only do Hispanics grow more businesses, but their women are more fertile. The idea, coyly hinted at, is that massive intermarriage between conservative Caucasian men and Hispanic women is the only thing that will save the Republican Party.”

Eventually, Dukie dragged me away from the exhibition hall and back to the lounge. By the time the evening’s main event rolled around, both of us were cross-eyed. The ceremony, scheduled to start at six sharp, was a black-tie event, and I somehow managed to squeeze into my old tux and make my way to the Grand Ballroom. Luckily, I found our place cards on a table well to the rear and out of the way. A shifty-looking waiter of indeterminate sex had just arrived with a carafe of white wine when Dukie and Kaylie made their entrance. I was astonished at the transformation. Kaylie, sans piercings, had remade herself in the spitting image of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s: black cocktail dress, velvet gloves up to the elbows, her hair arranged in an elegant chignon—everything but the long cigarette holder. Speechless, I looked at Dukie, who just shrugged. Looking more than a bit ragged around the edges, he wasn’t likely to last through the ceremony. With each new course, he grew more comatose, while Kaylie and I carried on a charming conversation, if you can imagine Audrey Hepburn as an anarcho-libertarian. As for the ceremony, it was, at the outset at least, hopelessly dull. Pat seemed lost without Vanna. The winners in the various categories were all very well behaved and quite predictable. You’ve heard all about them by now, of course. Lindsey Graham’s tearjerker A Bachelor for Life was widely expected to win Best Autobiography, and did—by a landslide. Not even the Poetry Prize for Maya Angelou’s Twenty-One Ways of Eating Jim Crow was really unexpected, particularly since it was an Oprah’s Book Club selection. My readers do not, of course, need to be reminded that the Nonfiction Award went to David Horowitz for his Paleoconned: Treason on the Right. Horowitz received tremendous applause for an acceptance speech that vociferously denounced the deviousness of the paleo fifth column, which disguises its collaboration with America’s enemies under the cover of “traditional values.”

Media reports have been somewhat confused about what happened next, but I recall distinctly that just as Sajak was about to announce the Fiction Award, the lights were suddenly extinguished, and several small explosions erupted in the area around the stage. Smoke filled the room, and pandemonium broke out. Someone screamed, “Stink bombs!” And, indeed, my nose began to fill with the nauseating odor of rotting flesh. I looked around for Dukie and Kaylie, but they had disappeared. Making for the door, I was all but stampeded by the frightened crowd, while alarms began to wail.

Piercing the din a shrill female voice could be heard shouting over and over, “Squeal, you Republican pigs! You pseudo-capitalist running dogs! Books are for blockheads!” And I could swear that, as I took a last look back at the stage, the diminutive figure holding the microphone wore a little black dress. Was I hallucinating? A number of “informed sources” have stated since that the prank was the work of the Occupy Movement, but I have my own ideas. Honestly, you shouldn’t always believe what you read.

Oh, and by the way, books bearing the Patriot seal are now selling like hotcakes.

Leave a Reply