“We need another Reagan.”

I’ve heard that too many times to count. Don’t get me wrong: I think another Reagan would be a good start—but only a start. Everyone should recall that Reagan, even during the six years that the Republicans held the Senate, was able to do little to trim back the size of the federal leviathan, let alone abolish programs that had been around only since the days of LBJ and Nixon (not to mention the Department of Education, signed into existence by Jimmy Carter a little more than a year before Reagan’s election).

Take a look at Reagan’s speech at the Republican National Convention in 1964. The entire speech is on YouTube. Reagan is brilliant. The speech is brilliant. Two years later he was elected governor of California. If only he had become president back then, when he still had all his mental faculties and acuity. Nonetheless, without the troops in the trenches, I’m not sure what he could have done. Great leaders and great leadership can inspire and rally, organize and direct—but without a strong base, not much will happen.

For most of our history we’ve had presidents who were anything but celebrities, and the country did just fine. The American culture of enterprise, individualism, hard work, family, religion, and racial homogeneity were firmly in place and kept America humming along. Presidents came and went. It mattered little. Few people can name such 19th-century presidents as Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, James K. Polk, Zachary Taylor, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, or Benjamin Harrison. Benjamin Harrison! Can anyone tell me anything about Benjamin Harrison or his presidency?

Even the 20th century has presidential figures who have fallen into obscurity. Most college students I encountered during more than 30 years of teaching, including 15 years at UCLA, could tell me next to nothing about William Howard Taft, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, or Herbert Hoover.

This isn’t necessarily bad. It means that America has always been far more, and far greater than, her presidents. This remains true, despite the electronic media helping to make the president a celebrity and exaggerating his importance. Look at what the media has done with Barack Obama—or, should I say, St. Obama the Messiah. He is truly a celebrity, and his fans are legion. As his term in office approaches the halfway point, though, even his admirers are beginning to find him wanting. Although he has had Democratic majorities in both the House and the Senate, his presidency is falling far short of the expectations those on the left had when he swept into office. The crowds of sheeplike people, some with tears running down their cheeks, fawning over him during campaign rallies, almost guaranteed that he would become a bitter disappointment. Those fans thought that he was going to save them—from everything, including themselves.

It embarrasses me that America has come to this, and I would be equally embarrassed and alarmed if the figure fawned over was on the right. We Americans are better than that, bigger than that, more independent than that, and more ornery than that. My wife’s paternal grandfather said he immigrated to America because he would neither step aside for, nor tip his hat to, any man. Are we now a people yearning and waiting for a celebrity politician to rescue us lowly peasants?

When I was growing up, one reason I was especially proud to be an American was exactly because Americans had an independent, ornery, rebellious, even defiant spirit. For me there is nothing like it. Remember when President Jimmy Carter decided we should go metric? Well, I had nothing against science simplifying calculations and using the metric system. But why mess with road signs? However, that is just what Carter did—despite his posturing as the down-home Georgia peanut farmer—because he was a liberal elitist who knew exactly what was best for the rest of us.

Large green signs began to dot our interstate highways with distance in kilometers. It infuriated me—and evidently infuriated others. Within days the signs were shot full of holes. I loved it. The signs were replaced. The new signs were shot full of holes. I loved it. The signs were again replaced, but this time with signs using good, old fashioned miles. No one shot them full of holes. No one felt the need to shoot them full of holes. The signs with kilometers, though—well, God bless the boys who squeezed off those rounds. Every bullet hole said, “I’m an American. F-ck you.”

This is all part of our tradition. Stepping aside for or tipping our hat to our putative betters is foreign to us. “There is nothing in America,” a European visitor to the frontier said, “that strikes a foreigner so much as the real republican equality existing in the Western States, which border on the wilderness.” The mountain men, sourdoughs, cowboys, teamsters, and others judged men on their individual merits, not on titles, lineage, or wealth. As a cowboy told a supercilious scion of British nobility, “You may be a son of a lord back in England, but that ain’t what you are out here.” When another British nobleman insisted on being addressed as “Esquire,” the cowboys laughed and said that they would be calling him “Charlie.”

“Superiority,” noted an English traveler, “is yielded to men of acknowledged talent alone.” A titled Englishman traveling through the cattle country of the northern High Plains brought a bathtub with him. When the Englishman ordered a hired packer to fill it, the frontiersman instead drew a revolver and shot the tub full of holes, telling the nobleman that he now had a shower. When an aristocratic visitor asked a Wyoming cowboy if his “master” was at home, the drover replied angrily, “the son of Beliel ain’t been born yet.”

For years I taught a college course on World War II. I delivered several lectures on the background of the war and, for the Pacific Theater, described in detail the Japanese army and navy, and Japan’s war in China long before America became involved. By the time I got to the battle for Guadalcanal, the students knew the Japanese forces and their arms well. Most of the Japanese who served on Guadalcanal were veterans of other campaigns and were all well trained and disciplined. Moreover, at that point their equipment and arms were equal to and occasionally superior to ours. Their Zero, for example, was clearly superior to the Wildcat fighter that the Marines flew. The Marine slogging his way through the jungle carried the old bolt-action 1903 Springfield rifle. The M1 Garand would not be seen on Guadalcanal until the Army arrived.

This all led students to wonder how in the world the Marines could have prevailed. The odds against them seemed enormous. I’ve read plenty on Guadalcanal and have talked with veterans of the campaign, including two of my cousins. It is clear that the individual Marine pilot and rifleman beat the veteran Japanese at their own game because that Marine was independent, ornery, rebellious, and even defiant. When the Japanese lost officers, they collapsed. They did nothing but charge in a mindless banzai fashion or commit suicide. This was celebrity politics on the battlefield. Their system required absolute submission and obedience to their officers and worship of the emperor.

While good leadership was critical to the Marines, that leadership was supplied not only by senior officers but by junior officers and NCOs as well. Some companies lost all their officers and were commanded by sergeants—effectively so. When Lt. Col. Chesty Puller contacted one of his companies that had been hit especially hard, a corporal came on the line. Puller asked him the condition of the company. “We have nothing better than sergeants left, sir,” said the corporal.

Puller growled into the line, “There is nothing better in the Marine Corps than sergeants.”

This was demonstrated again and again on Guadalcanal. A diary taken from the body of a dead Japanese major had this to say: “The Americans amaze me. I never violate the principles of warfare, and they never obey them.” He couldn’t understand how the Japanese were losing.

The Japanese command had to invent stories to justify their losses. Said one communiqué to Japan, “The Americans on this island are not ordinary troops, but Marines, a special force recruited from jails and insane asylums for blood lust.”

Japanese officers treated their men as inferiors and subjected them to brutal discipline. American officers hoped to earn the respect of their troops by never asking them to do anything they themselves wouldn’t do. On occasion, American officers even indulged their troops. Also taken from the Japanese major whose diary proved so revealing was his sword, a beautiful piece. The sword was put on display at Puller’s command post. It stayed there only a short while before it disappeared. One of Puller’s aides was indignant, exclaiming to Puller, “We’ll have a shakedown. We’ll turn it up in one of the bedrolls, Colonel.”

“Hell, no!” replied Puller. “I don’t know who got it, but any one of those boys rates it more than I do. They carried the big load. Let him keep it.”

Leaders in Washington could lose faith, but not the boys on the ground. A radio broadcast picked up on Guadalcanal in the early weeks of the campaign was listened to with rapt attention. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox was being interviewed. He seemed pessimistic about Guadalcanal and feared it could become another Bataan. With Puller and other senior officers, as well as assorted enlisted men, standing around the radio, a young Marine shouted, “How about that old bastard? Don’t he know we got real Marines on this island?”

Later in the campaign the Army arrived to reinforce the Marines. Chesty Puller’s battalion was holding part of the perimeter at Henderson Field. Puller had his boys string barbed wire in front of their positions and dig in deep, knowing that the Japanese were about to launch a major attack. An Army colonel soon arrived, telling Puller that his unit was on its way to help with the perimeter defense. Puller told the Army colonel, “I want you to make it clear to your people that my men, even if they’re only sergeants, will command in those holes when your officers and men arrive.”

The Army colonel without hesitation replied, “I understand you. Let’s go.” Can you imagine that occurring in the armed forces of any other nation?

Later, when the Japanese assault had been shredded and thousands of Japanese killed or wounded, a wounded Japanese officer was brought in alive. Through a translator Puller asked him, “Why didn’t you change your tactics when you saw you weren’t breaking our line? Why didn’t you shift to a weaker spot?”

“That is not the Japanese way,” said the officer. “The plan had been made. No one would have dared to change it. It must go as it is written.”

Puller’s junior officers and NCOs changed tactics and improvised on the spot. Many times it was sergeants making the decisions. The campaign cost Puller 24 percent of his enlisted men but 37 percent of his officers. Much of the credit for the perimeter defense of Henderson Field goes to three of Puller’s gunnery sergeants—Roy Fowle, Joe Buckley, and Red O’Neill—to say nothing of the individual heroics of such three-stripe sergeants as John Basilone.

After the Guadalcanal campaign, Puller was brought back to the states and made available for speaking engagements and interviews. Government officials thought that it would be good for home-front morale to have one of the key figures in the campaign describe how we defeated the heretofore invincible Japanese. Those officials got more than they bargained for from the salty and outspoken Chesty Puller and soon pulled him off the speaking and interview circuit. In speech after speech Puller emphasized that the individual American fighting man had made the difference. Said Puller, “I can’t tell you the Japs are no damned good because they are good. But we’re better. One American properly trained can handle two of the yellow bastards. They have discipline, and they use the jungle cover better than we do, but they can’t think on their own. They never change battle plans once they’re made, regardless of cost.”

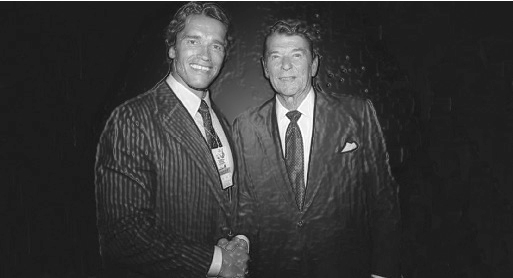

What American history tells me and what I’ve learned from my own observations confirms the wisdom of our frontier forefathers and the experience of the Marines on the Canal. We need good leaders, to be sure, and a telegenic and media-savvy presidential candidate with solid conservative credentials would be welcome. However, our base is far more important. If we create a strong base through grassroots efforts, then the rest will take care of itself. I saw California and the nation go ape over Arnold Schwarzenegger, the ultimate celebrity politician, when he ran for and won the governorship. There was even mention of amending the Constitution so a naturalized citizen—meaning Schwarzenegger—could become president. Republicans were in a frenzy. How silly that all seems now. I suspect the Democratic frenzy over Obama will soon seem equally silly to those who put their faith in him.

As Americans, we shouldn’t put our faith in media princes—or princes of any kind. No one is going to save us. No one is going to rescue us. We have to do it ourselves. I think that is what we are seeing in the Tea Parties. Nations and cultures are built from the ground up, beginning with the family. If we start with our own families, if we bring children into the world and inculcate them with our values, traditions, spirit, and sense of identity, then we shall not fear for the future.

At the Rockford Institute Summer School in 2009, one of those in attendance asked me what we can do to save our civilization. I told him all the usual things—things that are essential—but I didn’t think to mention that he had already contributed mightily to the cause. He was there with his wife and children. His children—young adults, really—were clearly steeped in our values, well educated, and highly accomplished. If we produce children like that, our future is secure. If we don’t, and we’ve certainly been falling down on the job lately, then no matter how many Reagans we have at the top, we will lose our country.

I’m not entirely pessimistic. I think Americans are best in a crisis. In fact, it usually takes a crisis for Americans to react. The Tea Parties are a reaction to an America at the crossroads. Moreover, the Tea Parties are clearly a grassroots phenomenon. These protesting Americans are not waiting for a politician to lead them. The phenomenon reminds me of those bullet holes in the highway signs. It remains to be seen if a politician will try to jump out in front of the Tea Party march as it gains momentum. I would not be displeased if such a politician got run over.

Let’s remember that, in America, power emanates from the people—not from princes.

Leave a Reply