Where then shall Hope and Fear their Objects find?

Must dull Suspence corrupt the stagnant Mind?

—Samuel Johnson, “The Vanity of Human Wishes”

At the time of writing in late August, the coming U.S. election is hard to call, so that dull Suspence must indeed prevail for a few more weeks. One need not let it corrupt one’s mind, though; nor is there ever any excuse for one’s mind to be stagnant. What can citizens of a conservative temperament reasonably hope for from the election? Is there anything they should reasonably fear?

So far as the immediate result of the election is concerned, there are three big headline possibilities: a Democratic victory, a Republican victory, or chaos.

To take that last possibility first, by chaos I mean an indeterminate result: neither party willing to admit defeat, with weeks—perhaps months—of political paralysis and social disorder. The idiosyncrasies of the U.S. voting system more or less guarantee such a result when the race is very close.

Indeed, they sometimes deliver a disputed result even in races not close. This most famously happened in 1876 when Samuel J. Tilden, the Democrat, won 51 percent of the popular vote against 48 percent for Hayes, the Republican. Confusion over the electoral college numbers led to a stalemate, resolved at last only by some political horse trading that awarded the presidency to Hayes. This remains the only U.S. presidential election in which the loser had won a majority, not merely a plurality, of the popular vote.

Indeed, they sometimes deliver a disputed result even in races not close. This most famously happened in 1876 when Samuel J. Tilden, the Democrat, won 51 percent of the popular vote against 48 percent for Hayes, the Republican. Confusion over the electoral college numbers led to a stalemate, resolved at last only by some political horse trading that awarded the presidency to Hayes. This remains the only U.S. presidential election in which the loser had won a majority, not merely a plurality, of the popular vote.

More recently, the 1960 election result was dubious, with John F. Kennedy’s margin in the popular vote a hairsbreadth of 0.17 percentage points and very plausible evidence for vote-counting shenanigans in Illinois and Texas. Then there was the 2000 ruckus about Florida’s count after George W. Bush squeaked out a win over Al Gore and Gore’s 0.54-percentage-point margin in the popular vote. That one had to be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The losing candidates in those elections yielded with various degrees of reluctance, but without any dogged nation-shaking defiance. Tilden bowed out the most eloquently: “I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.” Richard Nixon presented his concession to Kennedy as having been granted conscientiously, in the national interest, although some historians have argued that he had no choice and knew it. Gore’s concession in December 2000, “…what remains of partisan rancor must now be put aside…,” was so gracious that it prompted me to write at the time, as an epitaph on Gore’s political career, that “nothing became him like the leaving of it.”

Can we expect such gentlemanly restraint in today’s political atmosphere? I doubt it. The old codes are dead; gentlemanly restraint is now scorned as “toxic masculinity.” Hillary Clinton told the nation in an Aug. 24 interview on the Showtime documentary series “The Circus,” that in the event of a close result: “Joe Biden should not concede under any circumstances, because I think this is going to drag out and eventually I do believe he will win if we don’t give an inch, and if we are as focused and relentless as the other side is.”

Is there hope in the fact that both presidential candidates belong to the senior generation? Well, possibly. Both are older than Gore. Gore, however, is of the mid-20th-century political aristocracy, to whom noblesse oblige came by instinct. This was still understood 20 years ago but would go against the grain of our coarser, angrier time, whatever the private inclinations of Biden or Trump. Mrs. Clinton’s everlasting, ever-burning rancor is the new norm.

Of course,this assumes that Biden will still be in the arena on Nov. 3. There is widespread speculation about an October surprise in which he steps down, with Kamala Harris taking up the banner. Harris’ cast of mind is, I have no doubt, much closer to Mrs. Clinton’s than to Gore’s.

Of course,this assumes that Biden will still be in the arena on Nov. 3. There is widespread speculation about an October surprise in which he steps down, with Kamala Harris taking up the banner. Harris’ cast of mind is, I have no doubt, much closer to Mrs. Clinton’s than to Gore’s.

The prospect of a long, drawn-out, unresolved election result is mightily enhanced by the probability of widespread mail-in voting. Because of precautions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tens of millions of people will have ballots mailed to them, to be marked up and mailed back. Mail-in ballots are not new, but the number this year will be twice as great as it has ever been before—around 80 million, according to experts polled by The New York Times.

In a close election, chaos will certainly ensue. To note just one point of weakness, one of many: the postmark on a returned ballot should of course be no later than Election Day. Where this cannot be confirmed, the ballot should be discarded. Now, flip through some recent mail you have received, and note how few have a legible postmark.

And then there’s the potential for fraud. The Aug. 30 New York Post ran a long interview with an unidentified election “fixer” from New Jersey who claimed to have been manipulating elections at every level in that state for years, and to have mentored teams of vote-rigging fraudsters in New York and Pennsylvania. He covered all the bases in his interview with the Post: fake ballots (you can just photocopy them); crooked or partisan postal employees; votes from nursing homes; impersonation of habitually non-voting citizens (lists are publicly available); and plain bribery. Penalties for discovery are light, and electoral authorities would much rather not discuss the issue. The Post article concludes with the sentence: “The city Board of Elections declined to answer Post questions on ballot security.” Did I mention that this alleged fixer is a Democrat?

Supposing that disputes over the election result drag on for months, which seems quite possible, they might be further inflamed by verdicts in highly-politicized court cases. The three cases that most readily come to mind are the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia, in February; George Floyd in Minneapolis in May; and Jason Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin in August. Any of them might result in a verdict unpleasing to noisy political factions.

Accused in the Arbery shooting are three ordinary citizens, rather than law-enforcement officers, although one is a retired police detective. It could be a while before the Arbery case comes to judgment. The closest recent parallel of a court case involving a shooting by a citizen is the Trayvon Martin case in 2012 and 2013, which lasted 16 months from event to acquittal. For Arbery, that would put us in midsummer next year.

The Floyd and Blake cases involve police officers; at the time of writing, no charges have been filed in the latter case. The nearest recent parallel here is the shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer in August 2014. It was just three months from that event to a grand jury dismissing the case without an indictment.

Recall that the devastating Los Angeles riots of 1992 were triggered by the acquittal of police officers in the beating of Rodney King. That acquittal came a year and two months after the event.

So, the spring and summer of 2021 could be angry seasons. If, on top of that, our politicians are still fighting over the election result, we shall be an unhappy country indeed.

•

That is the chaos scenario. If there is a clear presidential result with no ensuing chaos, we shall either have President Biden (possibly Harris) or a second term for Trump. Within each of these situations there are sub-possibilities. Does the winning candidate carry both houses of Congress, only one, or neither?

In modern times it has almost always been the case that when a sitting president trying for a new term is overthrown, the winner brings both House and Senate with him—as happened with Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson. However, when a sitting president is successful in seeking a new term, the almost invariable rule is stasis: party control of Senate and House remains as it was, usually with an uptick in House seats but no consistent gain-loss pattern for the Senate. My best late-August guess is that a clear Trump win would bring the Senate with it but not the House, while a Biden (or Harris) win would likely put Democrats in control of both houses.

.jpg) A Trump and Senate win for Republicans would leave conservatives just where they are: with a president unloved by his own party’s legislators and ineffectual against the entrenched administrative state. In the words of a friend of mine: If 2016 brought conservatives the Flight 93 election—storm the cockpit and possibly die, or do nothing and certainly die—2020 will be the lifeboat election. Electing Trump will leave conservatives in a lifeboat bobbing helplessly, fruitlessly in mid-ocean, but at least still alive.

A Trump and Senate win for Republicans would leave conservatives just where they are: with a president unloved by his own party’s legislators and ineffectual against the entrenched administrative state. In the words of a friend of mine: If 2016 brought conservatives the Flight 93 election—storm the cockpit and possibly die, or do nothing and certainly die—2020 will be the lifeboat election. Electing Trump will leave conservatives in a lifeboat bobbing helplessly, fruitlessly in mid-ocean, but at least still alive.

It might also strengthen Trumpism. The Republican Party at its highest congressional and gubernatorial levels is still, for the most part, the party of George W. Bush, Mitt Romney, Paul Ryan, Mitch McConnell, Nikki Haley, and Bill Lee. It’s the party of invade-the-world, invite-the-world, keep-the-big-donors-happy institutional Republicanism—or, what the editor of this magazine is fond of calling “Conservative Inc.” There is not much Trumpism there.

It is a peculiarity of current American politics that Republican voters don’t much like their own party. Following Trump’s triumph in the 2016 Republican primaries, Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan posed the question: Have Republican Party managers engaged in any reflection on the fact that when their voters were offered 16 institutional-Republican candidates and one complete outsider, they chose the outsider? They had not; they still have not.

If Trump has failed to Trumpify his party, though, it is also the case that the party has not tamed Trump. To be sure, his words remain far ahead of his actions. On big issues that won him GOP primary voters four years ago—immigration, foreign military entanglements—he has accomplished little, and that mainly by executive orders which can be undone in a instant by a Democratic administration. Merely by being in the White House, though, and by continuing to bluster, however impotently, about these issues, he has kept Trumpism in play.

The Republican National Convention earlier this month was by no means a festival of Trumpism, but Trumpism was on display in brief flashes. There it was from Mark and Patricia McCloskey, the St. Louis couple who stood outside their home with guns to deter an anarchist mob advancing on it. There it was from a short, stirring speech by Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz. And there it was, briefly, from Trump himself, boasting of having personally scotched the plan by the Tennessee Valley Authority to bring in cheap foreign employees on guest-worker visas and to fire a corresponding number of Americans.

Trumpism has a beachhead in the Republican Party. With Trump in the White House for a second term there is the opportunity—not a certainty, but at least the opportunity—to fortify and expand that beachhead and begin to move inland.

A Biden (or Harris) victory, probably bringing with it a Democratic Congress, would return America to the malign trends of the Clinton-Bush-Obama years, and introduce some new ones as well.

The demographic revolution already long underway would kick into high gear. Biden has promised to amnesty illegal aliens already here, whose numbers are not known even to the nearest 10 million, enabling them to bring in tens of millions more by chain migration. The borders would be opened and enforcement of immigration laws would cease, adding tens of millions more. Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. would be granted statehood, guaranteeing Democratic supremacy in the federal government for decades to come.

In social and cultural matters, the creeping soft totalitarianism of recent years will become firmer and more shameless. Persons insufficiently enthusiastic about the aptly named DIE triad—Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity—will have no outlet for their opinions, and quite possibly no bank accounts or credit cards.

Economically, the crushing of the hated middle and upper-working classes by outsourcing and the importation of cheap labor will continue, to the advantage of transnational elites. The COVID-19 pandemic has already given a mighty boost to their “sandwich” policy, or what Sam Francis called “Anarcho-Tyranny”—pitting the top and bottom classes against the middle—by wiping out millions of small businesses.

Those are the hopes and fears for this coming election as best I can divine them. Now, back to nine more weeks of dull Suspence.

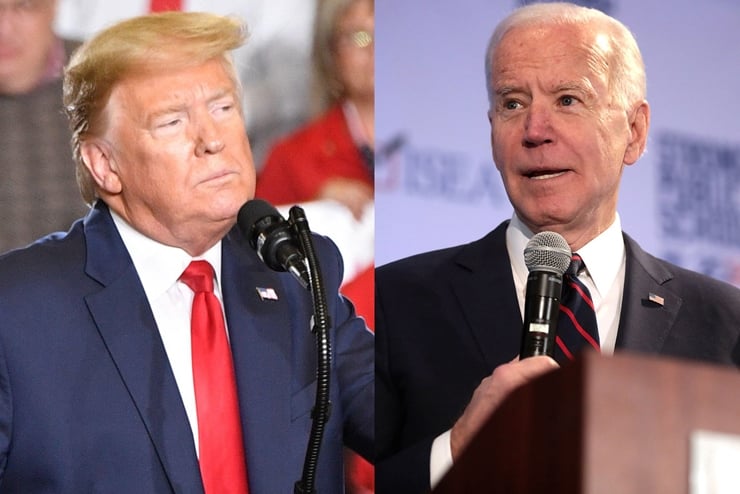

Image Credit:

above left: President Donald J. Trump at a campaign rally in Wildwood, N.J., on Jan. 28, 2020 (Ron Adar / Alamy Stock Photo)

above right: Former Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., at a campaign event in Des Moines, Iowa on Jan. 18, 2020 (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply