The Economist contemptuously called him France’s “wannabe Donald Trump.” He’s been accused by The Atlantic of using the “Trump playbook.” Not to be outdone, Britain’s New Statesman dubbed him a “TV-friendly fascist.”

French anti-racism and rights groups, including SOS Racisme, have filed complaints against him. Already thrice convicted of inciting racial hatred, he is due to appear again in French court on similar charges. Former French president François Hollande called his views “obscene and shameful.”

“He” is Éric Zemmour, a French TV pundit who, in the words of Vanity Fair, is “sucking up all the media oxygen in France.” That oxygen is fueling Zemmour’s meteoric rise on the French political scene, which is shaking up the right and terrifying the left. But apoplexy among the chattering classes has severely impaired sober analysis of the Zemmour phenomenon. The question, above all, is whether he will present a viable alternative vision of France’s future. That requires evaluating Zemmour in the context of modern French history, for his ascent is a consequence of France’s elites neglecting the real values of the French people.

The son of North African Jews, Zemmour was enjoying a successful career across the full spectrum of French media as a controversialist until 2014, when he published a book titled Le suicide français (The French Suicide). Then came the Islamist assaults on French soil in 2015, notably the Bataclan theatre attacks which killed 90 people. Zemmour and France haven’t been the same since.

In his books and media appearances, Zemmour attacks a wide variety of targets, including feminism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, NATO, the Euro, and even bans on smoking in restaurants. But Zemmour’s main focus is on France’s Muslims, whose numbers the Pew Research Center calculates will rise to almost 13 percent of the country’s population by 2050. Besides advocating that French mosques be closed, Zemmour wants most immigration to France stopped, and supports deporting illegal immigrants.

In recent years, Zemmour has attracted hand-wringing coverage from journalists inside and outside France. But when he hinted in February 2021 that he was actually contemplating a run at the French presidency in 2022, opinion-makers from all over the political spectrum scrambled to denounce him, in a striking example of elite piling-on.

When, on Nov. 30, 2021, Zemmour formally announced he would run for the presidency, he was polling ahead of Marine Le Pen, the leader of the right-wing National Rally party, and not far behind Emmanuel Macron, the sitting president. If Zemmour ends up in second place in the first round of the two-round presidential election, he will go to a run-off against Macron. Even though virtually every pundit concedes he doesn’t stand a chance of becoming president, the “country is captivated,” in the words of The Nation, by the possibility of Zemmour’s candidacy.

Zemmour’s political ambitions have so unsettled journalists outside France that they misinterpret his true significance. Mainly they ignore the French historical context, as with the allegation that he is France’s Donald Trump. It is true that both individuals are not shy in front of the TV cameras and have exploited the media to advance their political agendas. Beyond this superficial resemblance, however, Donald Trump is no Zemmour. No two people could look more unlike than the balding, gnome-looking Zemmour and the broad-bodied Trump with his wispy comb-over.

Trump would never be described as an intellectual, while Zemmour is that rare politician who may actually write his own books, as he claims. Both men criticize their respective countries’ immigration policies. Trump, however, is mostly concerned about America’s southern border with Mexico, while Zemmour stresses the threat to France from Muslim newcomers.

If the Trumpist label doesn’t fit, other opponents of Zemmour claim he harbors counterrevolutionary dreams of regime change, similar to those of the right-wing insurrectionists who took to France’s streets back in 1934 and almost toppled the country’s beleaguered and rudderless Third Republic (1870-1940). Yet, other than lamenting the power of France’s courts, Zemmour has never expressed interest in overturning the constitution of the current Fifth Republic founded in 1958, the brainchild of former president Charles de Gaulle.

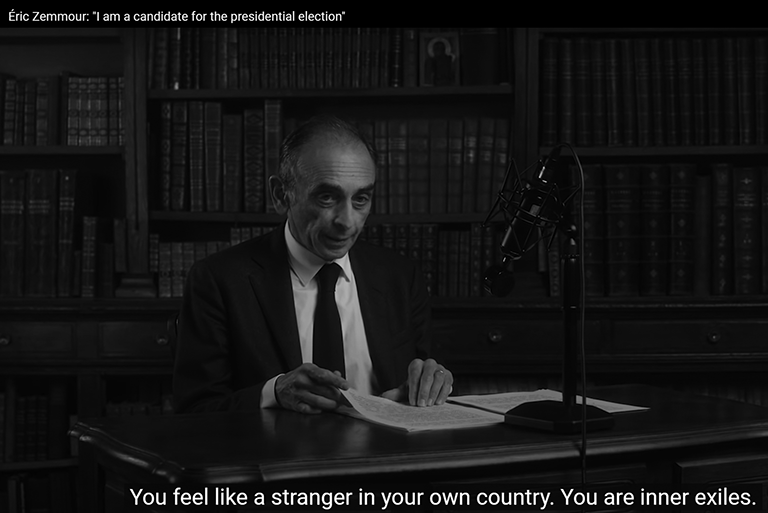

Zemmour is more Gaullist than he is a man-on-horseback Boulangist. (Georges Boulanger was a French general and politician, whose nationalist followers attempted to overthrow France’s corrupt government in 1889.) Indeed, Zemmour claims to be de Gaulle’s “ideological heir.” When he announced his candidacy for the presidency in a video posted on social media, he sat at a desk reading his words in front of an old-fashioned microphone, meant to recall de Gaulle’s June 18, 1940, broadcast to a defeated France. He praises de Gaulle for cutting ties with France’s former colony Algeria in the 1960s, temporarily relieving France of the task of assimilating Algeria’s Muslims. Zemmour loves to quote de Gaulle’s own words: “I don’t want my hometown to become Colombey-les-Deux-Mosquées.” (De Gaulle’s family home was located in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises.)

Put another way, there is nothing that Zemmour has said with which “The General” would have disagreed, were he alive today.

The de Gaulle-Zemmour connection goes even further. De Gaulle’s genius lay in both his handling of the Algerian crisis and giving France a constitution that for the most part ended bitter conflicts over its form of government. The 1789 revolution had triggered a century and a half of turmoil pitting monarchists, socialists, republicans, Bonapartists, and garden-variety authoritarians against each other.

Eric Zemmour at a campaign rally on Dec. 5, 2021, in Villepinte, north of Paris (Rafael Yaghobzadeh / Associated Press)

Versions of these political rivalries weakened France’s attempts to stem the German invasions of 1870 and 1940, as well as defeat independence movements in France’s former colonies, Vietnam and Algeria. De Gaulle’s constitution mitigated the effects of France’s endless parliamentary squabbling and its revolving-door coalition governments by making the position of president more than ceremonial.

France’s government under the Fifth Republic, resembling America’s balance of powers among its three branches of government, has withstood mass street protests ranging from the student and worker strikes of 1968 to the Yellow Vests of 2018. Apparently Zemmour sees in the Fifth Republic’s ideals the principles that France’s governing classes may pay lip service to, but covertly reject as outdated.

Zemmour faces severe condemnation from many fellow French Jews. He has drawn the ire of Jewish groups with his contention that Vichy France (1940-1944) did its best to protect France’s Jews from Nazi clutches, and has questioned the standard narrative about Alfred Dreyfus, who in 1906 was formally exonerated by the French government of charges that he was a spy for Germany.

France’s chief rabbi recently declared that Zemmour was “anti-Semitic certainly, racist obviously.” Author Bernard-Henri Lévy, like Hollande, described Zemmour’s views as “obscene.” But Lévy went further to say that Zemmour “desecrate[s]… the name of our people” with comments that insult Jewish morality. Zemmour is guilty of “inflaming the worst obsessions of the far right,” Lévy insisted.

Similarly, Ian Buruma, the former New York Review of Books editor, said Zemmour betrayed his Jewish identity by giving “license to bigotry among gentiles.” Zemmour represents the “revenge of Vichy,” according to Buruma.

But perhaps there are simpler, if politically less convenient reasons behind Zemmour’s ascent. Zemmour is likely less optimistic than some other French Jews about the possibility of peaceful coexistence with Muslims. For centuries, his Jewish ancestors lived among Berber Muslims in Africa. In 2015, the president of Paris’ Black Jewish community told The Times of Israel that the ancestors of French Jews who once inhabited Arab lands in Africa suffered at the hands of Muslims, and “the situation was not good for them there.” Hence many Sephardic Jews in France vote for right-wing parties and politicians, who reflect their concerns about a larger Muslim concentration in France.

Maybe many French Jews like Zemmour feel the same as Chile’s Jews, who as a small minority alongside the country’s Palestinian community of 350,000 (the largest outside the Middle East), tend to back a right-wing candidate for Chile’s presidency. When Jews have “a feeling of siege,” in the words of a Chilean Zionist, they look to politicians who offer them the most security.

Éric Zemmour announces his candidacy in a Nov. 30, 2021, YouTube video. (Éric Zemmour / YouTube)

In France, notably after the 2018 murder of a Holocaust survivor in her own apartment by a Muslim Frenchman yelling “Allahu Akbar,” it would be understandable if French Jews no longer felt safe in their own country. This was the sentiment of the protagonist’s girlfriend in Michel Houellebecq’s 2015 novel Submission, who ultimately decides to emigrate to Israel. The growing number of Islamist terrorist incidents on French soil prompts the question: as the nation’s Muslim population increases, is it time for France’s half million Jews to consider leaving?

In any case, the Zemmour phenomenon is a reminder that he is best understood against the background of French modern history. The truth is that he is an outspoken defender of French sovereignty and law and order who believes that rotten elites are following policies that are quickly destroying France.

In fact, it is the globalist elites who embrace multiculturalism and internationalism that are the true threats to liberty, if we associate freedom of speech with democratic governance. The multitude of victims of our current cancel culture testify to this threat. The elites of France are the ones who have banned Zemmour from Instagram and hauled him into court for inciting “hate.” France’s state media authority has also ordered him off his news channel, on which he used to debate guests from all sides of the

political spectrum.

This is all in stark contrast to surveys which say that a sizable percentage of the French population agrees with him that they are threatened by immigration from Africa. Even president Macron, with an eye cocked towards the polls, has proposed legislation to combat Islamist “separatism.” Who claims to defend the real France: Zemmour or its elites?

From this perspective, Zemmour’s presence on France’s national scene is not evidence of “hate,” despite what his detractors contend, but rather a sign that the French still prize traditional values of patriotism and natural justice. His ascent in politics may prove to be evanescent, but in the meantime many of the policies he is advocating enjoy broad acceptance among the French population. To his detractors he may look like a “wannabe Trump,” but in reality Zemmour is as French as haute couture or nouvelle cuisine.

Leave a Reply