Among the terms of endearment applied to Americans who worry about present immigration policy is “xenophobe.” This high-toned word normally precedes lower-toned ones—”racist,” “bigot,” “neo-Nazi,” etc.—which take over as the exasperation level rises.

A “xenophobe” is someone who fears foreigners. Fears them why? No dictionary is competent to say. Every xenophobe doubtless has his own reasons. I raise the point not for Freudian but for analytical reasons. Xenophobia, whatever connotations the word may take on in the mouths of the liberal establishment, speaks to a reality of human existence: to wit, there are foreigners we’d damn sure better fear. Or at the very least keep an eye on.

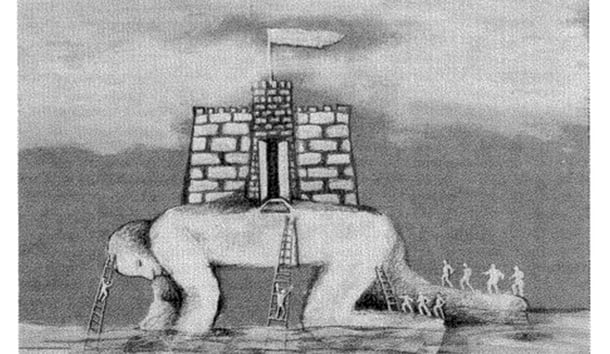

Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes—”I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts.” What a shame the Trojans in general lacked Laocoon’s appreciation of the wooden horse situation. Caught with their xenophobia down, they lost everything. And the peoples of Central Asia in the time of Genghis Khan? They should have gone to bed affirming pluralism and brotherhood?

There is one modern example of a people whose xenophobia was too languid for their own good. I mean the Mexicans of the early 19th century. Had the Mexicans, and the Spanish before them, possessed the sense to shut out my buckskin-clad forbears, scratching themselves and smelling no doubt of bear grease, nudging their wagons through the piney forests of the Sabine region, or debarking on the sandy beaches of the Gulf Coast, Texas might be a different place today. That would not make me happy personally. There is every likelihood that in such an event I would be living in, say, North Carolina.

What Spain and Mexico lacked was a critical mass of xenophobes, ready, out of cultural pride, to point out the Gringo Peril, to close their minds fast to entreaties concerning brotherhood and diversity, to utter a curt but meaningful: No—nunca, señores, nunca. They didn’t, and that’s that. Still, the sibilant sí of 200 years ago, which ushered in the Gringo era, has residual resonance. And maybe more than that.

What the Spanish, and subsequently the Mexican, authorities did was open Texas to Anglo settlement—for entirely logical and understandable reasons. The Spanish policy began, indeed, in the Missouri country, around the time of the Declaration of Independence. The population of the Louisiana territory at that time comprised only 20,000 Europeans, mostly French, and Spain sensed the tenuousness of its hold on the place, what with Anglos rapidly establishing themselves in Kentucky, If the Anglos were going to come, asked Don Francisco Bouligny, commander of the Missouri area, might not they be domesticated by land grants and oaths of allegiance to the Spanish crown? The Spanish governor was amenable, actually deciding not to notice that few if any of these prospective newcomers were Catholic.

By 1787, the Spanish were actively recruiting Americans, and many accepted. The contrasting cultures lived peaceably enough. There was more than ample room for them. In any case, the Louisiana Purchase mooted the whole matter of cultural rivalry.

With no adverse experience in Louisiana to deter them, the Spanish found it logical to practice pluralism and diversity in Texas. Hard realities backed up this logic. In 1820, Felipe Enrique Neri, Baron de Bastrop, a Dutch-born colonizer, denoted two such reasons for the Spanish governor’s consideration. One, Comanche Indians generally controlled the country north of Bexar (San Antonio) and east to the Sabine River. A few more Indian fighters, with a personal stake in winning, would not come amiss. Two, the Spanish and Mexicans clearly had no desire to live in Texas; more of them were moving out than moving in.

Baron de Bastrop spoke in support of the petition of an old friend, Moses Austin of Missouri, who in pre-Louisiana Purchase days had been regarded as a loyal subject of His Most Catholic Majesty. Moses Austin saw Texas as a new promised land. There he proposed to bring in hardworking settlers, grant them property, and watch civilization flourish. The hard-line military commander of the area, Arredondo, who had brutally but efficiently snuffed out republican uprisings, agreed. The right sort of Anglo-Americans—as opposed to the wrong sort, who earlier had made military forays into the area—would come in handy, militarily. If they happened to own slaves, so much the better. Property gave them a stake in peace and order. The Romans had reasoned similarly when they began recruiting barbarians into the army.

The Provincial Council in Monterrey had hopes that all would work out well. It said in a resolution: “Therefore, if to the first and principal requisite of being Catholics, or agreeing to become so, before entering Spanish territory they also add that of accrediting their good character and habits . . . and taking the necessary oath to be obedient in all things to the government, to take up arms in its defense against all kinds of enemies, and to be faithful to the King, and to observe the political institution of the Spanish monarchy, the most flattering hopes may be formed that (Texas) will receive an important augmentation in agriculture, industry, and arts by the new immigrants, who will introduce them.” What more could a host government hope for? The appropriate oaths were sworn and, under the leadership of Moses Austin’s gifted son Stephen (Moses having died), the new settlers tackled the land and the Indians.

By 1835, more than 1,500 American families had come to Texas under Austin’s sponsorship. “In a single decade,” writes historian T.R. Fehrenbach, “these people chopped more wood, cleared more land, broke more soil, raised more crops, had more children, and built more towns than the Spanish had in three hundred years.” The experiment worked so well that other impresarios besides Austin were authorized to bring in their people. In addition, the border being unguarded, numerous Americans slipped in discreetly, without invitation. “Undocumented workers,” or “illegal aliens,” it would have been fair to call them.

The Anglo-American population of Texas rose to 20,000 by the mid-1830’s (by which time independent Mexico had supplanted Spain as the colonial power). For every Spanish-speaking Texan, five spoke English. North of San Antonio, the ratio was one to 10. The seeds of discord had been planted.

The Mexicans had not feared these Greeks who bore the gifts of industry and outward loyalty. (“Gringo,” coincidentally—the name often applied by Spanish-speakers to the Anglos—comes from the Spanish for Greek, “Griego.”) Where were the xenophobes—the foreigner-fearers? Quiet or inactive, though with exceptions.

In an 1830 speech to a secret session of the Mexican Congress, a member said: “Mexicans! Watch closely, for you know all too well the Anglo-Saxon greed for territory. We have generously granted admission to these Nordics; they have made their homes with us, but their hearts are with their native land. We are continually in civil wars and revolutions; we are weak and know it—and they know it also. They may conspire with the United States to take Texas from us. From this time on, be on your guard!”

As we all know, such words proved prophetic. The Anglos played their part—and a valuable part it was—in Mexican society. But tensions and strains intensified. Cultural conflict set in.

No university sociologists existed at the time to explain away, or pooh-pooh, differences in cultural outlooks. There was—is—in fact a Hispanic way of looking at life; there was—and remains so, though in apologetic and watered-down form—a Northern European way. “If Nordics saw Latins as somewhat degenerate, tyrannical, slavish, and cruel,” writes Fehrenbach, “Latins considered the Northerners arrant barbarians.” Mexico’s various coups and insurgencies, its frequent changes of government in the postcolonial period, “convinced North Americans that the Mexicans were an inferior race. It was impossible for Anglo-Americans to respect a people who could not rule themselves.”

“The leadership of each nation,” Fehrenbach says, “operated on a different plane of thought. Americans always made two basic assumptions: the American nation was more vigorous and certainly superior to the Mexican; and that the western lands in question were useless to Mexico, which had been unable to settle them. Americans expected Mexicans to accept both assumptions reasonably. But in reverse, the American assumption of superiority lacerated the immense Latin pride of the Mexicans, and the fact that their empire north of the Rio Grande was vulnerable suffused Mexicans with such fear and suspicion that it became almost phobia among the upper classes.” Xenophobia at last! But too late. Ahead lay the Alamo and San Jacinto, and the Lone Star flag.

What is the lesson? To be careful who is let in through the front door, knowing that once the door is open, open it may remain. This is true no matter how noble, how broadminded may be the intentions of hosts and guests alike. To begin with, one never knows what kinds of guests will follow the first set: how strong their commitment to concord and cooperation will be.

The peaceable and judicious Stephen F. Austin was not the Mexicans’ problem. Nor were his colonists necessarily the problem. The dynamics he created in Texas—North Americans streaming in, bringing with them inevitably the manners and mores and viewpoints of their former home, coming to think of themselves less as guests than as rightful owners—that was the problem. What else was to be expected? The Spaniards, given the necessities of the frontier, had reason to worry more about the short run than the long run (in which, as Keynes a century later would dryly observe, we are all dead). The long run got to Texas faster and more furiously than anyone in the 1820’s probably expected.

And today? There is some reverse symmetry. By the year 2030—the same time span that separates us from the Goldwater-Johnson presidential campaign—whites in Texas are projected to become a racial minority. I repeat: a minority. Blacks and Hispanics added together will outnumber and, theoretically at least, outvote them. This is chiefly because of the strong inflow of Mexicans, under way for more than two decades, coupled with the high Mexican birthrate. Texas’ strong labor market, contrasted with their own country’s weak one, makes Texas (like California) attractive to them. The Texans want restaurant and hotel workers, maids, gardeners, common laborers of all sorts. Well, here they are! They come with great ease, the Rio Grande border being notoriously porous. As with the North Americans, 175 years ago, many of the newcomers arrive legally; many sneak in any way they can. In 1990, according to the Census Bureau, nearly a million Mexicans living in Texas were born in Mexico. The figure is indisputably much larger now. As to how many are here under color of law—¿quien sabes?

The cases—Texas in 1821 and 1997—are not entirely comparable. For one thing, after almost 200 years of life lived together in a land of opportunity, Texas whites and Hispanics are reasonably well acquainted with each other: certainly far better acquainted than in the years leading up to San Jacinto. Cultural differences persist, many of them powerfully. On the other hand, no difference I know of makes the races want to duke it out—physically, culturally, whatever. The famous fight scene in Giant—Bick Benedict (Rock Hudson) battles on behalf of a humble Mexican family about to be ejected from a greasyspoon cafe—was barely credible 40 years ago. If it were filmed today, allegedly concerning today’s Texas, Texas audiences would roll their collective eyeballs.

In the days of racial segregation, when Southern blacks and whites attended different schools, Texas counted Mexicans as white. And how about this? The elected student council president of my junior high school in 1955, in a town where Mexicans were few and far between, was . . . Moses Ramirez.

So is fear of foreigners passé, a nightmare from unenlightened times? That would be the wrong conclusion to draw from a study of early 19th-century Texas history. There are and always have been foreigners we’d damn sure better fear. Or if not “fear,” in the full, cold-sweaty, panic-stricken sense of that emotive word, how about “watch with healthy skepticism”? No marriage of Greek words expresses that sentiment with exactitude, but English can serve as well, if more garrulously, in this context.

Texas history gives us valuable pointers in the dynamics of immigration: how, for practical reasons, the established culture holds open the door for an outside culture to enter; how the outside culture, once inside, establishes itself; how growing numbers give to its voice timbre and depth and volume; how the outside culture maintains over the miles, many or few, its distinctive outlook; how that outlook, asserted strenuously enough, produces divisions and tensions that put the quest for power at the center of life. We all know what happens, do we not, when humans fall to feuding over power.

The expulsion of Mexican authority from Texas, in 1836, does not prefigure the expulsion of Anglo authority from Texas in 2036. But to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest (as the Book of Common Prayer would have it) that history lesson is the commonest of common sense. What lesson of life is plainer than that those who live life are not all alike; that in the age of political correctness, as in the age of imperialism, the world’s peoples differ from each other; that differences, unreconciled, can explode into conflict?

Watch John Wayne and Richard Widmark in The Alamo. On general principles I recommend the experience.

Leave a Reply