By a curious coincidence, bills to legalize gay marriage are passing through the British and French parliaments almost simultaneously. While other countries like Spain and Portugal legalized gay marriage years ago, London and Paris are acting together on this—rather as they have done in Libya, Syria, and now Mali. The British and French bills were presented within days of each other to the parliaments in London and Paris; the first debates started within a week. No doubt these bills will be approved close together later this year.

The simultaneity of the procedures, however, cannot hide the radical differences between the neighboring countries in the debate. In France, gay marriage is being promoted by a newly elected Socialist president with a comfortable Socialist majority in parliament. In 1999, the last Socialist government in France undertook a similar move when it introduced civil partnerships. (In theory, these were intended for same-sex couples; in fact, 96 percent of them are concluded between persons of the opposite sex.) Then as now, the proposed measure is vehemently opposed—as one would expect—by the political right.

In Britain, by contrast, the normal rules of left-right politics have been inverted. Gay marriage is being forced onto the statute book by a Conservative prime minister, David Cameron, who has said on many occasions—for instance when he held a reception at No. 10 Downing Street in July 2012 for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people—that he is personally deeply committed to it. (So passionate, indeed, is he about these issues that in 2009 he publicly apologized for a law passed in 1988 by his predecessor Margaret Thatcher, which prohibited the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities.) He is supported by the big guns of his government and party—the chancellor of the exchequer, the foreign secretary, the home secretary, and the minister of education, as well as by other cabinet members and at least half of the Conservative members of Parliament. The result of Cameron’s political cross-dressing is that there is no organized parliamentary opposition to the proposal. The two other major parties, Labour and the Liberal Democrats, support it. And so, whereas the French parliament—traditionally mocked as an empty shell by pompous British constitutionalists—is resounding to fierce debate, the parliament in Westminster will host few significant exchanges on the subject. What debate there is will be between different wings of the now bitterly divided Conservative Party and outside Parliament.

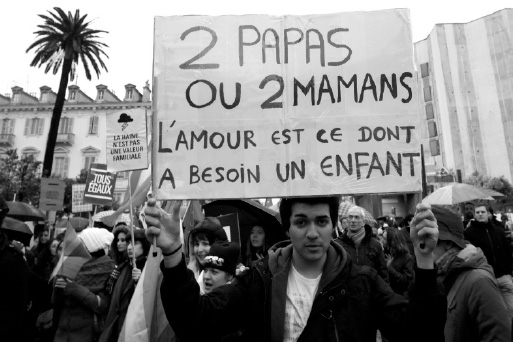

The same differences apply to the public reaction to the bill. In France, the demonstrations against gay marriage have been the biggest in a generation. Two sizable demonstrations were held in November 2012 in Paris (one gathered hundreds of thousands, the other tens of thousands), while on January 13 of this year over one million people marched through the streets of the capital. In Britain, there has been nothing—no demonstrations or marches have been held, no movements have been set up to oppose it, no public personalities have declared their hostility. No one has even dreamt of saying, as people have said in France, that the new law could pave the way for polygamy and incest.

The key structural factor behind the vigorous public reaction in France is the Catholic Church. Her bishops and clergy strongly encouraged people to travel to Paris for the demonstration on January 13, even though (or perhaps because) it was explicitly non-Catholic, “against homophobia,” and open homosexuals were given a prominent place among the speakers at the final rally. The march’s success was resounding, especially since the demonstration in favor of gay marriage two weeks later managed to get only a few tens of thousands of people out into the street.

In Britain, meanwhile, the Anglican Church has ascended new heights of ridicule by remaining officially opposed to gay marriage, while having just agreed, in January, to allow men in civil partnerships with other men to become bishops. Some of the opposition to the new law has come from clerics who complained that their churches were not consulted before the government made it illegal for gay weddings to be conducted in places of worship. The message of the Catholic Church in England, meanwhile, has been strong enough on paper, but in the media the archbishop of Westminster (the leader of England’s Catholics) is mainly heard complaining about matters of procedure—there was no white paper, there were no previous manifesto commitments—as opposed to speaking in the apocalyptic and civilizational terms the issue demands. Archbishop Nichols has in any case made a fool of himself by previously saying that he is in favor of civil partnerships.

However, neither structural nor organizational matters are the key to these differences between France and Britain: The key is culture. These recent events confirm that Britain is one of the most atheistic and revolutionary societies in the world. France may have lost massive ground since she merited the title “eldest daughter of the Church,” but hers remains a profoundly conservative society, at least in comparison with her northern neighbors. This much becomes strikingly clear when one understands that the most contentious issues of the gay-marriage law in France—the consequences it will have for children—have already been voted onto the statute book in Britain without so much as a peep of protest.

The slogans on January 13, and the campaign message of the center-right opposition in the French parliament, have concentrated exclusively on the effect of the proposed changes on family law. They have not, in fact, discussed the specific issue of gay marriage itself. People carried banners affirming that children have (or should have) a mother and a father; they attacked the implications of the bill for the laws on filiation; they protested against gay adoption; they campaigned against medically assisted procreation for gay couples. These are the neuralgic points for the French population, where family values remain strong.

This is because family values, in the literal sense of the term, are an integral part of French marriage law. In the French civil code, marriage is defined explicitly as a relationship oriented toward the creation of a family. Couples receive from the state on their wedding day a livret de famille, an official document that begins with the marriage certificate and then has space to fill in the children. (There is room for nine.) When he conducts a marriage ceremony, the public official (the mayor or his deputy) must by law read out the relevant parts of the civil code so that the couple understand what they are committing themselves to:

The married couple ensures together the moral and material direction of the family and they provide for the education of children and prepare their future. . . . Parental authority is a group of rights and duties whose finality is the interest of the child. It belongs to the mother and the father until the child reaches the age of majority . . .

In Britain, by contrast, there is no legal connection between marriage and children. The words that the law requires the spouses to pronounce as their marriage vows contain no reference to children or the family. The vows are in that sense purely contractual, concerning as they do only the spouses’ commitment to each other. The legal fulcrum of marriage, therefore, is individualistic in Britain, whereas in France it transcends the promise between the two partners and reaches out into the future to underline their obligations to as yet nonexistent persons, their children.

Current French law on adoption and medically assisted procreation reflects this. Adoption by homosexual couples is not permitted, nor is medically assisted procreation (artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization). Medically assisted procreation is provided only to couples of childbearing age who have been medically diagnosed as sterile: It is a medical treatment based on a formally established pathology, not a lifestyle-choice service offered free to those who want it. The new law would change this; hence the strong opposition to it.

In Britain there is none of this. To general indifference, adoption by homosexual couples was legalized in Britain in 2005. Indeed, the following categories of people are allowed to adopt children: “single, married, in a civil partnership, an unmarried couple (same sex and opposite sex), the partner of the child’s parent”—in short, anyone. Not only may homosexual couples be considered for adoption, but the equality legislation in Britain is so draconian that Catholic adoption agencies who refuse to place children with homosexual couples have been forced to close down.

The same goes for medically assisted procreation and surrogacy. Medically assisted procreation is available in Britain to anyone who wants it. Surrogacy is not recognized by law but is tolerated de facto. In addition, the law on filiation itself has been changed to reflect these new “realities.” Thanks to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008, if a lesbian in a civil partnership with another woman conceives through artificial insemination or fertility treatment, both women are legally the child’s parents. This concerns not just the legal recognition of filiation but the birth certificate itself: On April 18, 2010, for the first time, a birth certificate was issued for a child which bore the names of two women as her parents, that of her artificially and anonymously inseminated mother, and that of her mother’s lesbian partner. In the United Kingdom, in other words, birth certificates are now being falsified in the name of politically correct ideology. This goes even further than what is being proposed, controversially, in France, where the possibility of having the words father and mother replaced by the term parent will apply only to the adoptive filiation and not to the birth certificate itself.

These legal changes have been possible because of the all-pervading ambiance of tolerance that reigns in British society. Two famous Conservative politicians—one a minister, and the other a member of the European Parliament—have boasted in published articles about how their children have been, respectively, bridesmaid and pageboy at a civil ceremony uniting two men, and about how one of their daughters has a godmother who is in a civil partnership with another woman. Such statements reflect the default setting of the British middle classes, including so-called conservatives: When faced with change, they muddle through, sigh, accept all novelty (however radical), or even welcome it as trendy. The default setting of the French middle classes, by contrast, is genuinely conservative—in cuisine as much as on social issues. The so-called revolutionary French are in fact Europe’s main reactionaries. Thank God.

Leave a Reply