Those who know C.S. Lewis’s short book The Four Loves will remember that Lewis speaks of the four different kinds of love: affection, friendship, eros, and charity. But, in a preliminary chapter about “likings and loves for the sub-human,” he writes about “love of one’s country” or patriotism. He points out that, in the first place, “there is love of home, of the place we grew up in or the places, perhaps many, which have been our homes; and of all places fairly near these and fairly like them; love of old acquaintances, of familiar sights, sounds and smells.” Then he makes an important comment: “Note that at its largest this is, for us, a love of England, Wales, Scotland, or Ulster. Only foreigners and politicians talk about ‘Britain.’” That is, patriotism encompasses primarily a cultural, not a political unity.

What can we glean from Lewis’s account of patriotism? Actually, Lewis might have put patriotism in his next chapter, on affection, the kind of love we have for members of our family, for parents, children, brothers, and sisters. And the thing to note about patriotism, as about affection, is that it makes no pretense about the things, or people, we love. We love our family not because we claim our family is the best in the world (how could we ever know that?) but because it is ours. Within very broad limits, we are comfortable with it, we feel (more or less) relaxed within it, we understand its ways. Even of a very dysfunctional family, we might say that we understand its ways in a manner that we might not of a family that we recognize as (objectively) more healthy. That more healthy family is not our own, however much we might wish that our own family resembled it more. As Lewis said, “[A]lmost anyone can become an object of Affection; the ugly, the stupid, even the exasperating.”

So with countries. It would surely be foolish for anyone to claim that his own country was the greatest in the world, for again, how could he ever know? Few of us have lived in enough places to make such a judgment, and the complexity of social life would, in any case, most likely lead us to say that, in some ways, this country is better, while, in other ways, that country is better. However, it is not by weighing such factors that we come to love our own country. We love it, as we love our families, because it is ours; we feel at home with it, and, however much we may dislike or even detest certain of its characteristics or habits, we know that we could never truly feel at home anywhere else.

Lewis speaks “of the place we grew up in or the places, perhaps many, which have been our homes; and of all places fairly near these and fairly like them; love of old acquaintances, of familiar sights, sounds and smells.” He says nothing of political boundaries here. Indeed, he explicitly rejects such boundaries, for, by speaking of “a love of England, Wales, Scotland, or Ulster” and not of “Britain,” which is the political unit, he indicates what surely is obvious, that patriotism grows from the local. And this must be true not just for the English, but for us as well. Love of our home city or locale, of our state or region—e.g., the Midwest or the South—surely must precede love of the partial abstraction, the United States of America. I am not denying the possibility of a patriotism that involves the entire country, but I only note that it must begin with a locality and be based on a locality, if it is to be really patriotism and not its counterfeit, nationalism.

The two points, then, that we can deduce from the above discussion are these: Patriotism is love of something merely because it is our own (not because we claim it is the best), and patriotism always begins with the local.

C.S. Lewis further discusses the idea “that is sometimes called patriotism . . . that our own nation, in sober fact, has long been, and still is markedly superior to all others.” He notes the obvious fact that every nation is apt to think in this manner and relates the following humorous story.

I once ventured to say to an old clergyman who was voicing this sort of patriotism, “But, sir, aren’t we told that every people thinks its own men the bravest and its own women the fairest in the world?” He replied with total gravity—he could not have been graver if he had been saying the Creed at the altar—“Yes, but in England it’s true.”

This story, by itself, ought to be enough to disabuse us of the notion that we or anyone else can rightfully consider his nation the best or greatest, for, if we consider it laughable in the case of England, surely we can see that they—or the French or Russians or Argentines—might consider it equally laughable in the case of us. No, this is not the sort of thing that constitutes genuine love of our own place.

As to the second point—that patriotism is always local—that is likewise important. Governments have been established in many and diverse ways in the history of the world, and although, for the past 200 or so years, we have generally identified each political regime with a nation, in the sense of a presumed cultural or ethnic unity, this has been more of a fiction invented by politicians than a reality. The famous remark by some politician following the unification of Italy, “Now that we have created Italy we must create Italians,” could equally be applied to many another country, such as Germany, where Bavarians were famous for their dislike of Prussians, or the Russian Empire, which included peoples as dissimilar as Lithuanians, Armenians, and Tartars, and even more the Soviet Union, which was explicitly based not on any cultural unity, real or feigned, but on socialist ideology. A Lithuanian patriot surely loved his small country, not the vast czarist empire or, still less, the Soviet incarnation of “socialism in one country.”

And this brings us to our own land. The first thing to note about us is that, although it remains possible for us, the genuine patriotism that Lewis writes about has been almost entirely replaced with a nationalism that not only ignores the local but replaces love of one’s own people with love of an abstract idea.

Now nationalism has not always meant the same thing in every place or age, but, I would maintain, it has always denoted something abstract, something that pretends to be patriotism but has nothing to do with affection for one’s place and people. In 19th-century Europe, nationalism generally meant a supposed love of one’s own people, but this love was founded not on place and familiar habits but on the abstraction of the semimythic nation. Nationalism in this sense was political, not cultural. Having created the abstraction “Italy” or “Germany,” although peasants from Northern Italy or Northern Germany could not even fully understand the speech of their southern brethren, nationalists fought to unify everyone who was held to be their kith and kin into one political entity, which was to be beloved equally, no matter where one lived. Instead of loving one’s valley or village, they were to love whatever territory happened to be included within the political boundaries of the artificially created abstraction. These political divisions were based on fictions. Why were the German-speaking Swiss excluded from Germany? Why were the Dutch, who speak what could be considered a low-German dialect, not regarded as German? Moreover, a traveler going from France into Italy in the 19th century would have noticed a gradual change of local dialect, from something recognizably French into something recognizably Italian. But where should the mystic national boundary be placed? Wherever it is placed is largely arbitrary.

These realities were no hindrance to the nationalists’ project: The abstraction of the nation was what was important, not the real and concrete place. A real patriot would have loved his own village and region even if, perchance, a political boundary cut through it. A nationalist, on the other hand, loved his own people insofar as they were defined by a political boundary, or were held to be prevented unjustly from joining in that political unity, as in the case of Germans in Poland or Bohemia after World War I.

Not every nation has the same sort of nationalism. Sometimes, a nationalism has been based on the notion that the nation is the bearer of some universal message for mankind, as in the France of the Revolution and Napoleon. But this kind of nationalism is still an abstraction; it is not an affectionate love for one’s own people and place. And a similar kind of nationalism has afflicted and poisoned our own notions of patriotism in the United States. Perhaps the clearest example of this comes from Woodrow Wilson’s Second Inaugural Address (March 5, 1917): “We shall be the more American if we but remain true to the principles in which we have been bred. They are not the principles of a province or of a single continent. We have known and boasted all along that they were the principles of a liberated mankind.”

In his January 31, 1990, State of the Union Address, President George H.W. Bush declared that “America, not just the nation but an idea, [is] alive in the minds of people everywhere. As this new world takes shape, America stands at the center of a widening circle of freedom—today, tomorrow, and into the next century.”

And, in a notable example of the confusion of patriotism and nationalism, William Bennett, secretary of education in the George H.W. Bush administration, in an article, “Horatius at the Bridge,” in the Journal of Family and Culture, wrote about the Roman hero Horatius, who held an army at bay on a narrow bridge so his fellow Romans might have time to cut the bridge behind him. He thus faced nearly certain death to save Rome. Bennett quotes from Thomas Macaulay’s poem:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The captain of the gate:

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can a man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers

And the temples of his gods?”

This is certainly an example of real patriotism, “the ashes of his fathers / And the temples of his gods.” But how, then, does Bennett continue? He writes of certain American high-school students who “saw no moral difference between the United States and the Soviet Union.” And he comments,

I have to wonder what Horatius would say about such moral confusion. I wonder what he would say to the greatest nation on earth; a democracy that has attained gifts of political and individual freedom equaled for centuries only in dreams; a country that raises some of its brightest children to regard the values of a totalitarian police state as morally commensurate with its own.

Now, whatever else Horatius might have felt about Rome, he died because Rome was his, not because he felt Rome had “attained gifts of political and individual freedom”—or any other gifts at all. We may hope that the inhabitants of each region of the earth love their own place, even those who are tragically forced into exile, as Solzhenitsyn continued to love Russia. He did not transfer his patriotism to the United States when he was forced to live here, even though he might have recognized that the American citizen had more of “political and individual freedom” than the Soviet citizen did. But Bennett confuses love of one’s place with love of an idea. Would he have us cease to love our own place if, in the future, we no longer had those “gifts of political and individual freedom”?

The abstraction of American nationalism, then, lies in seeing this country more as an idea than as a real place. And, since this idea is held to embody “the principles of a liberated mankind,” it follows quite logically that we have a right and a duty to extend that idea to the rest of the human race. Here is how Calvin Coolidge put it in his Inaugural Address (March 4, 1925):

We stand at the opening of the one hundred and fiftieth year since our national consciousness first asserted itself by unmistakable action with an array of force. . . . Under the eternal urge of freedom we became an independent Nation. A little less than 50 years later that freedom and independence were reasserted in the face of all the world, and guarded, supported, and secured by the Monroe doctrine. . . . We made freedom a birthright. We extended our domain over distant islands in order to safeguard our own interests and accepted the consequent obligation to bestow justice and liberty upon less favored peoples. . . . Throughout all these experiences we have enlarged our freedom, we have strengthened our independence. We have been, and propose to be, more and more American.

I could easily supply a dozen more such quotes, but these must suffice to show the prevalence of our own brand of nationalism. And moreover, I submit that, in the United States, normal patriotism has been almost entirely swallowed up by such nationalism. That is, we have been taught from childhood to feel and to express patriotism as nationalism, so that whatever healthy patriotism exists among us is generally unable to articulate itself. Even if an American might feel a genuine love of people and place, as soon as he begins talking, he almost automatically speaks the language of nationalism, a nationalism that wants to assert not that this place is mine, and, thus, I love it with a love of affection, but that this place is best, and, therefore, the “less-favored peoples” of the world had better prepare to be governed and shaped by us since we hold in trust for them “the principles of a liberated mankind.” Such nationalistic hubris should be repugnant not only to any Christian but to any honest man with a modicum of humility. But a true American patriotism, like a true English patriotism, must always be based simply on affection and must begin with the local, however far it might extend after that.

How far can patriotism extend beyond the boundaries of one’s own locale to embrace a wider entity such as, in our case, the vast United States? I think true patriotism becomes more difficult as the country for which we are supposed to hold it grows larger. Although, in the Federalist, the writers argued that, because of the unique features of the proposed Constitution, a republic of a larger size than the world had hitherto known could flourish, we must remember that Hamilton and Madison had in mind a country that extended, at the most, from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. Perhaps even they would have been daunted by the notion of one extending across the entire continent and even beyond. (Moreover, we should keep in mind that they were addressing the political viability of such an expansive republic, not the possibility of patriotism.) But, in addressing this question, we must first examine the notion of a shared historical past. Lewis himself refers to it as “a particular attitude to our country’s past.”

I mean to that past as it lives in popular imagination; the great deeds of our ancestors. Remember Marathon. Remember Waterloo. “We must be free or die who speak the tongue that Shakespeare spoke.” This past is felt both to impose an obligation and to hold out an assurance; we must not fall below the standards our fathers set us, and because we are their sons there is good hope we shall not.

This feeling has not quite such good credentials as the sheer love of home. The actual history of every country is full of shabby and even shameful doings. The heroic stories, if taken to be typical, give a false impression of it and are often themselves open to serious historical criticism.

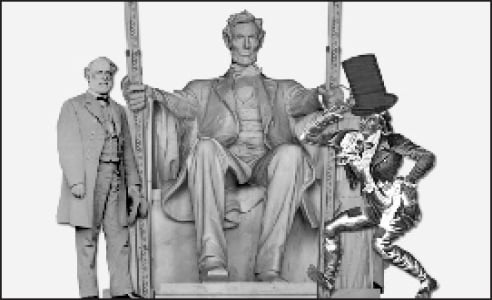

Now we Americans, like the English, have such shared history, and it, too, is often “open to serious historical criticism” and equally “full of shabby and even shameful doings.” Moreover, it has a somewhat artificial quality about it, in that it is officially taught and imposed (or, at least, it was in my schooldays) and extends backward beyond the real historical experience of many of our actual ancestors. Although many of us had no forebears in the United States during the Revolutionary War or even the Civil War, we are invited to appropriate for ourselves not only the Foundering Fathers but the Puritan settlers, and even to extend our historical memory back into medieval England. For, just as Lewis mentions the Battle of Marathon (surely not an English event!), we are invited to see ourselves as the heirs of Magna Carta, of the 1688 invasion of England that deposed the Catholic James II, and of the other events of what Herbert Butterfield called the Whig interpretation of history. This, in itself, should raise some questions for any Catholic, such as myself, with a sense of tradition.

The real issue, however, is whether a shared history, whether it be a true history or not, is sufficient to bind together people and places so far apart—whether a true patriotism can extend itself so far, or whether it necessarily becomes too attenuated. If Lewis thought that the United Kingdom was too large to serve as a genuine locus of patriotic affection, what are we to think of the United States?

At this point I must become less analytical, because I am less certain of what the truth is. I do confess that, during several long car trips that I took back and forth from Ohio to the Southwest during the 1970’s, I felt a spontaneous affection for many of the small towns I passed through, especially for the more rundown and shabby ones. I did feel a kinship with them, although hardly with the shiny cities. Traveling across the country did truly, I think, awaken a kind of affection in me, though this had nothing to do with any shared historical memory—a memory that, for the most part, leaves me cold. So I am unwilling to assign any strict geographical boundaries to genuine patriotism, except to say that, if it is not rooted in one’s own small place, then it probably will never be able to extend itself to anything as large as our entire country. Nor is there anything wrong, I think, in recognizing degrees of patriotism—less intense as one moves away from one’s locale, more intense as we return to our own place. In my own case, I could never feel the same intensity of affection for any other place as I feel for Ohio, especially northwest Ohio, where I was largely reared.

In any case, it is imperative that we both recognize and reject the abstraction of nationalism. America is not “an idea, alive in the minds of people everywhere.” She is a place. Any notion of America as a project founded on certain propositions or ideas, which constitute the “principles of a liberated mankind,” is totally foreign to any genuine patriotism. If we love our homes, our towns, our states, our country, we ought to love them as we love our parents, our siblings, our children. And that is rarely without some lively sense of their failings. For, as Lewis said of affection, it “will arise and grow strong without demanding any very shining qualities in its objects.”

Leave a Reply