On May 5, President Joe Biden left out the word “God” in his proclamation on the annual National Day of Prayer. Some critics on the right claimed Biden was the first president in American history to do so. Of course, those detractors fail to mention that the National Day of Prayer commemoration only dates back to 1952. Still, while all the uproar may seem to have been a tempest in a teapot, Biden’s omission was significant.

One account claims it was purely accidental—a gaffe originating with a White House staffer. But even if that were true, it is not unreasonable to suppose the Democrats who stalk the corridors of power in Washington these days would be perfectly content to see the name of God, no matter how far removed from any specific religious or denominational identification, disappear from public discourse.

Biden’s gaffe then, may be regarded as symptomatic of the dismal state of civil religion in America today—if, indeed, an American civil religion was ever anything more than a confabulation of historians and sociologists. Despite its advocates’ claims, American civil religion was insubstantial prior to the Civil War. It was after that conflict, I would argue, as the consolidated Union began to impose its will upon the various regions of the erstwhile republic, that a civil religion emerged in support of the growing nationalism of the day, one focused especially upon the cult of Abraham Lincoln.

For close to a century, the myth of the unity of the American people persisted and even flourished. Only with the ignominious defeat in Vietnam did its triumphalist grip slacken. Today, that quasi-religious faith is embattled and shredded, its heroes are under attack, and its rituals have largely been desacralized and mocked.

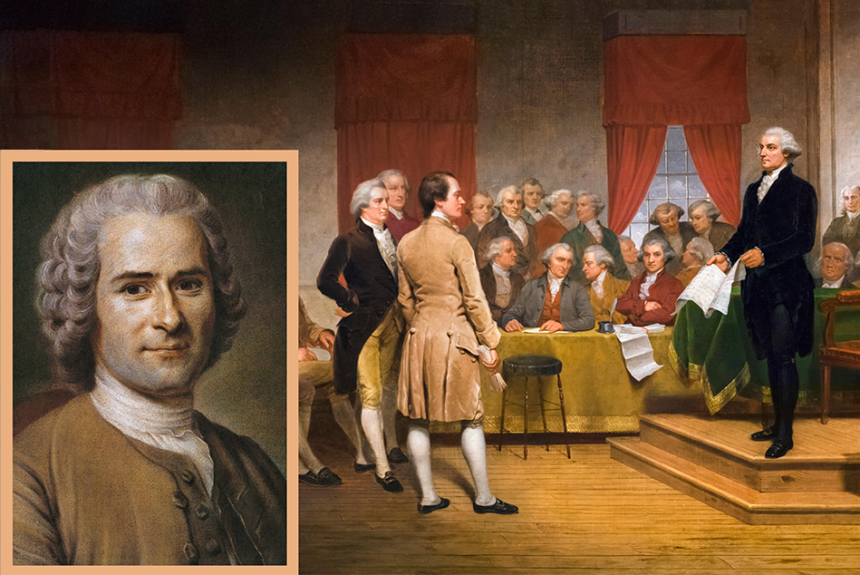

The first shot over the bow in the debate over a national creed was Robert Bellah’s 1967 essay “Civil Religion in America.” Bellah was not the first to use the term. Credit for that is owed to the Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. But Bellah was the first American scholar to articulate the lineaments of a civic faith that most Americans had unwittingly long professed. “Few have realized that there actually exists alongside of and rather clearly differentiated from the churches an elaborate and well-institutionalized civil religion in America,” he wrote.

Wearing the mantle of a social scientist, Bellah simply revealed what was hiding in plain sight. While he does not endorse wholesale Rousseau’s doctrine (which can be found in The Social Contract, 1762), he doesn’t fundamentally disagree that civil religion must include, in Bellah’s words, “the existence of God, the life to come, the reward of virtue and the punishment of vice, and the exclusion of religious intolerance.”

For Rousseau, the existence of God and the hereafter are important primarily because they guarantee virtue or vice will receive their due. The immediate end of civil religion is an ethical one. It shapes in citizens a moral consensus, not only about private but also, most importantly, public matters. Yet this ethical purpose is subordinate to a larger one: true freedom through national unity. The freedom of the individual can only be realized within a national community. This is a somewhat paradoxical claim, yet it is grounded in the Hobbesian idea that outside the security of the state the individual is subject to the “war of all against all” and, thus, unable to enact liberty’s prerogatives. The national unity Rousseau exalts stands under the ultimate political authority of the state, and civil religion serves its ends.

Rousseau’s models of true civil religion are pre-Christian, and particularly Roman. In that context, the religion of the emperor is the religion of the state; indeed, the gods themselves are, in a sense, servants of the state. Of course, the religions of the ancient world were not really “civil” religions as we understand them. No separation of Church and State existed. Between the priesthood and civil authority, there was no conflict.

Out of this perception arises Rousseau’s hostility toward Christianity, whose “vile” influence weakened the Empire and brought about its collapse—a variant on the arguments made by historian Edward Gibbon a few years later. The problem was Jesus himself, who “came to set up on earth a spiritual kingdom, which, by separating the theological from the political system, made the State no longer one, and brought about the internal divisions which have never ceased to trouble Christian peoples.”

In Bellah’s reconstruction of American civil religion, this problem hardly comes into view. Somehow, the overwhelming predominance of Christian faith among the American people never presented an obstacle to the emergence of widespread belief in the sacred and providential role America was destined to play on the world stage.

The American state, as a democratic republic, was never typically regarded as a potential usurper of divine authority, nor was there any attempt to sacralize the authority of the Union, at least not until sovereignty was removed from the States themselves. Bellah merely touches on this issue, and seems satisfied with Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that American settlers “brought with them into the New World a form of Christianity which I cannot better describe than by styling it a democratic and republican religion.”

If we delve a little deeper here, we will understand how American Christianity’s character helped shape our public dogmas. A helpful guide is Ellis Sandoz, a distinguished scholar well-versed in the formation of political religions. In Republicanism, Religion, and the Soul of America (2006) he argues persuasively that early Americans were profoundly influenced by a Whig tradition that had its religious roots in early British reformers such as the English scholar William Tyndale, and was mediated by 16th century political writers such as the Anglican Richard Hooker.

Within this tradition emerged a conviction that it was the duty of Christians to transform the secular, political realm. According to Sandoz, 18th century Christians in America attempted “within limits, to apply Gospel principles to politics: The state was made for man, not men for the state.” Despite his flawed and sinful nature, man “remains capable with the aid of divine grace of self-government.”

While it is no doubt true that many among the founding generation embraced the Whig theological persuasion, and traces of such thinking can be found in a number of texts, including George Washington’s 1789 inaugural address, Bellah’s case for an institutionalized civil religion prior to the Civil War is sketchy. The most one can say is that the doctrine that emerged after the Gettysburg Address was already present in some embryonic form. According to Bellah, the Civil War was the turning point, best expressed in the Gettysburg Address, at which a “theme of death, sacrifice and rebirth enters the new civil religion.”

above: Robert Neelly Bellah, American sociologist and Elliott Professor of Sociology at University of California, Berkeley (Aguther/Wikimedia Commons)

Bellah’s Lincoln idolatry is palpable. The Gettysburg Address was part of the “Lincolnian ‘New Testament’” Bellah wrote, and quoted Robert Lowell as saying it may be regarded as “a symbolic and sacramental act,” and that in Lincoln’s martyrdom “the Christian sacrificial act of death and rebirth” are fused with the American faith in freedom and equality for all.

Among the many essentially secular rites and ceremonies of our public faith, none has been as important as Memorial Day. The origins of Memorial Day are contested. At least half a dozen different localities in both the North and the South claim to have been the site of the first Memorial Day observances, but only in the South, initially, did these observances include prayers for both the Confederate and Union dead.

In April, 1866, the Ladies Memorial Association in Columbus, Georgia decorated the graves of all the fallen warriors in their local cemeteries, making a special point of honoring the Union dead who, after all, had been buried far from home with no one to honor them. After this exemplary act by women who were the mothers, widows, and sisters of slain Confederates, word spread into the Northern papers, inspiring the key figure behind the origins of a national Memorial Day, Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, John Logan, to issue General Order No. 11, designating May 30 as a day of remembrance across the land. There is little doubt that Logan was sincerely inspired by the ladies of Columbus, yet it is not, perhaps, too cynical to suggest that Logan’s directive was an act of appropriation in the service of a republic now on the brink of transformation into an imperial nation-state.

Whatever Logan’s deepest motive, the nationalization of Memorial Day with a fixed date at the end of May meant that the hundreds of local observances, celebrated on a variety of dates, became absorbed into the generic American civil religion, which now included the veneration of the Stars and Stripes. Though we are often led to believe that Americans of every class, race, and region embraced this new national observance, that is simply not the case. In the South until World War I, the various Confederate memorial days aroused greater devotion, and the persistence in the South of the Lost Cause movement signaled a deeply rooted refusal on the part of Southerners to be reconciled to the powerful current of triumphal Americanism sweeping the rest of the nation.

To his credit, Bellah lamented the role played by our civil religion in drumming up support for foreign wars. Yet the commitment to spreading a supposedly universal principle of equality beyond the nation’s shores had long since been enunciated by Lincoln, and by Jefferson, in one of his more idealistic moments, before him. The invasion of the South was simply a rehearsal for the bloody occupation of the Philippines in 1899, and for the crusade to make the world “safe for democracy” that rallied Americans in support of World War I.

Millions of Middle Americans today are far more suspicious of flag-waving adulation for all things red, white, and blue than they were in 1967. We no longer place much faith in American “exceptionalism,” and though a slim majority of Americans might pay lip service to the notion that we are still a “nation under God,” it is reasonable to ask: which God? We are no longer, in any significant sense, a Christian nation. For more than a century, most Americans undoubtedly understood the “God” of civil religion—the God invoked at the inaugural ceremonies of our presidents—in their own terms as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and St. Paul, no matter how divested He was of distinctive Judeo-Christian garb.

Today, we are an utterly secular and multicultural nation. What sort of God can be embraced by Christians, Muslims, Jews, neo-pagans, Buddhists, Taoists, and atheists with anything like unanimity?

Some have argued that today we are divided by two competing civil religions. One of them is wholly secular and liberal, devoted to the advancement of absolute equality, fueled by antiracist dogma and the vitriolic hatred of “white privilege.” The other is a remnant of the old faith that still clings feebly to life in the heartland. In other words, the civil religion that once produced a semblance of national unity is now a gravely wounded thing.

Rather than deploring this state of affairs, we might instead consider the possibility that the collapse of a unifying civil religion, and the slow implosion of the nation-state that it served, offers liberating possibilities. The disunity of the American people may result in growing violence and fratricidal conflict. Or, it may generate local and regional movements toward radical decentralization and a new independence from the vampiric monstrosity in Washington D.C. that has drained us all of our political lifeblood.

Image Credit:

above: detail from Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention by Junius Brutus Stearns, oil on canvas, 1856 (Ian Dagnall / Alamy Stock Photo) inset: portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, pastel on paper, 1753 (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply