“Sic Semper Tyrannis.”

—from the Great Seal of the

Commonwealth of Virginia

“I want everybody to hear loud and clear that I’m going to be the president of everybody.”

—George W. Bush

“I hope we get to the bottom of the answer. It’s what I’m interested to know.”

—George W. Bush

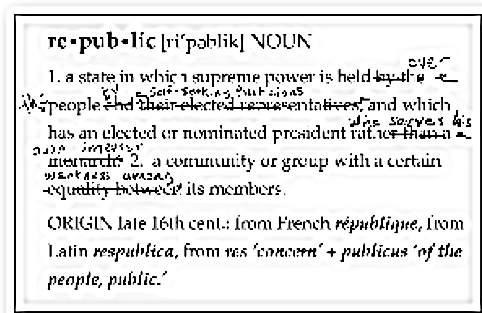

A bit of folklore, often retailed, reports a remark made by the sage Ben Franklin at the conclusion of the Philadelphia convention that drafted the U.S. Constitution. Franklin is supposed to have said: “Well, gentlemen, you have made a Republic—if you can keep it.”

The story is hokey. Except for one point, everything about it is designed to give a false impression. The delegates had not “made a Republic.” There already existed 13 republics recently created by the political genius and physical and moral courage of various communities of Anglo-Americans.

What the convention had “made” was a draft proposal to make “more perfect” collaboration among the 13 republics and any future republics to be created by their kinsmen and descendants in nearly empty lands to the west. The proposal could be accepted—or not—by the sovereign people of each republic according to their judgment as to its suitability for preserving “the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.”

The Franklin folklore was fabricated in the 19th century to infect the public mind with new implicit assumptions about the origin and nature of American government. This was part of a deliberate drive by the Massachusetts elite to create an “American” consciousness compatible with their ideas, interests, and will to power. The existence of this drive and its primary responsibility for many developments in American history up to the present moment can be empirically demonstrated by abundant evidence.

To postulate that the men of Philadelphia had “made a Republic” is to make American self-government and liberty seem a treasure miraculously created and handed down by a body of saints. The Constitution becomes Holy Writ, an object for awe rather than a human contrivance made flesh by the consent of the people who, it was once thought, knew what they intended it to mean. The Constitution, while untouchable by the profane hands of the people, is, at the same time, rendered mysterious and, thus, vague and malleable. The “consent of the governed” becomes a one-time thing, like being “born again.” Consent means eternal obedience to the masters of the government the Constitution created rather than the ongoing, revokable agreement of a living community to its government, as envisioned in the Declaration of Independence.

The true part of Franklin’s supposed statement is the “if you can keep it” part. All present would have agreed that republics—governments of the many—are hard to have and even harder to keep. All the experience and knowledge of the human race indicated that to be so.

The only real surety for good government was in the virtue of the ruler, whether power rested with the one, the few, or (especially) the many. The requirements of republican virtue were widely understood. They were exactly what the Founding Fathers meant by patriotism: admirable behavior in the public good, not the worship of rulers that many Americans now confuse with patriotism. The virtue required of republican citizens did not involve going to Sunday school or even helping your neighbors. It involved qualities of character necessary to preserve a republican government from an inexhaustible supply of usurpers and other dangers.

A virtuous citizen was discerning in the public business, able to detect the guile that lurked behind pleasing and plausible rhetoric. The ambitious and self-seeking at all times seek to aggrandize themselves through the state at the expense of the decent majority content to go about their private business. Frankness and skepticism and an alert suspicion of power were preferred in a republican citizen, as well as the ability and the courage to see and do what was in the long-term interest of the commonwealth, even when it seemed inexpedient or too demanding in the short term. Highest of all republican virtues was the willingness to risk life and property to defend liberty. The liberty to be defended indivisibly combined the freedom of the citizen and the self-government of the community—it was the freedom of the citizen in the free community. The free community was pre-governmental. It was society, a creation of Providence, not a creation of men like a particular state apparatus. A republican polity consisted of responsible heads of households, who, in order to keep their liberty, individual and communal, must be watchful, public-spirited, and always ready to resist enemies, foreign and domestic. “We dare defend our rights!” was once an American watchword, as was “Sic semper tyrannis!”

On August 22, 1992, at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, an American woman, standing in the doorway of her home and holding her baby, was murdered at long range by a foreign mercenary sent by the U.S. government—part of a 400-man militarized “law enforcement” group attacking the lonely Weaver homestead on the pretense of serving a trumped-up warrant.

How should a people of republican virtue react to this vile, illegal, unjust, and grossly tyrannical act of government? No government officials have been held accountable except in mild or ineffective ways. While many people have futilely disapproved, it would appear that not only the government and media but a majority of the American people tacitly approve the action of the government or at least are not offended or alarmed. (A multitude of other acts of tyranny, not necessarily so lethal, could be pointed to.)

Must we conclude that the American majority is no longer able to identify acts of government tyranny, much less respond to them, and is therefore empty of republican virtue? What did control its response? Was it a vague subjective feeling unrelated to the law or the facts—that the Weavers were bad people, antigovernment rednecks whom nice Americans find alien, disagreeable, and threatening? A feeling that government agents are “ours” and, therefore, are good and incapable of wrongdoing?

It is a long way from “We dare defend our rights!” to Ruby Ridge.

It would take the lifetime of a good historian to lay out in full how we got from there to here. We can, however, describe some of the main turnings on the road.

The triumph of Lincoln and the Republican Party in 1865 and its aftermath had at least three results worth emphasizing in this context. First, the people no longer had any means of constitutional action to resist whatever faction might be in control of the federal machinery. The states, described by Jefferson as “the best bulwark of our liberties” and previously considered to be the seats of the multiple sovereignties of the people, had been violently castrated. They could still oppress their own citizens, but they could no longer provide any resistance to the oppressions and usurpations of those at the controls of the federal juggernaut.

Second, institutionalizing a trend that had been evident from the beginning, the federal government became primarily an organization for the transfer of wealth. Ever since, our government has been a plutocracy where “democratic” choices are limited to safe alternatives pre-approved by those who control the money supply and other great aggregations of capital and who prefer to have government acquiescence and assistance in their activities. For a long time, the material, intellectual, and character resources of the American people created such prosperity, and so large a part of business and life was outside the sphere of government control, that it did not seem to matter very much. However, when a government becomes an engine for dispensing benefits, the public good disappears from sight. There is no reason why the feds should not tax the whole Union to support Cleveland’s Rock ’n’ Roll Museum or the senator from Hawaii’s wish to subsidize a Hebrew school in France. And “lawmakers” whose primary business is distributing bounties inevitably lack a republican long-term perspective. The debt that is to be left to future generations is of no immediate consequence and does not enter into their calculations.

Third, the power of Lincoln’s pretty phrases diverted the public discourse from a realistic debate on the public business into homiletical verbiage that hides more than it reveals—e.g., “war to make the world safe for democracy.” The outer limit of this poisonous mode has been reached by George W. Bush, whose discourse is full of attractive labels and devoid of content. (He evidently learned to read—assuming he did—by the look-say method.) Nothing he says bears any relation to the Constitution, to the will of the people, or to the real world outside of his self-referential universe.

Another turn in the road we can see was made in the “Progressive Era” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There was superimposed upon the American polity a regime in which “democracy” was no longer the will of the majority. It was, instead, a future goal in the reaching of which “experts” were to give the people what was good for them. The people were not to be consulted and often not even to be informed of why certain things were being done to them.

The regime of Plutocratic-Progressivism (the two things are inseparable), acting frequently through the great foundations and unaccountable to the people, writes the decrees that govern vast areas of “public policy.” Its two greatest triumphs are, first, Deweyite compulsory schooling, which spectacularly succeeded in depriving much of the population of real literacy, substantive knowledge, and capacity for reasoning. (George W. Bush has said: “Sometimes when you study history, you get stuck in the past.” “You teach a child to read, and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test.”)

Its second triumph has been to produce a century of warfare, still going on with a vengeance, using the blood and treasure of Americans to impose Plutocratic-Progressivism on the world. It is impossible to find any exercise of power more foreign to the letter and spirit of the Constitution to which the governed once consented.

A cultural historian can discern that the driving force in both the Lincolnian and the Progressive revolutions, and the main beneficiary of them, was a self-appointed elite spreading out from “the City Upon a Hill.” John Taylor Gatto, in The Underground History of American Education, describes it well: “It looks to me as if the energy to run this train was released in America from the stricken body of New England Calvinism when its theocracy collapsed from indifference, ambition, and the hostility of its own children.” In pursuit of an ideal future for the human race, the righteous “change agents” of New England approached other Americans as lab rats to be experimented on. Both the Lincolnian and Progressivist revolutions were strongly reinforced by the immigrants and educational gurus of Northern Germany, who believed that governments created people, not the other away around.

Much of the political behavior of Americans looks more like Germanic state worship than Anglo-Celtic individualism. Neither the devolved Puritans nor the German statists ever had any self-doubts or gave any notice to the wills and value of others.

We have also reached the extreme limit of “guardian democracy.” The U.S. government no longer protects American society. It is now in the business of democide—destroying the potential life and well-being of your descendants and mine. Ask the citizens of Columbus, Ohio, who recently had 60,000 Somali Bantu settled among them by the U.S. government, with free houses. Our massive invasion of immigrants could not possibility exist in a regime serving the long-term interests of its people. Republican government has ceased to exist when ladies whose families have been here since the 1600’s must be body-searched at the terminal gate to avoid offense to suspicious-looking, ungrateful foreigners. The rulers no longer see any difference between citizens and foreigners. And none dare defend their rights.

The industrial, transportation, and communication revolutions and the disappearance of an agrarian base inevitably altered the Founding Fathers’ vision of the character of a free people, as did the conquest of the electoral process by a two-party system representing little except politicians’ lust for power and plunder. To understand fully what has happened to us would take us deep into cultural history. How did a mass culture of triviality, superficiality, celebrity, and the reduction of leadership in the commonwealth to the puerile Me-ism of the President-of-Everybody come to dominate so much of our public (and private) life? Does television corrupt American culture, or does American culture corrupt television?

How our republican virtue got broken can be explained in many ways. How it can be fixed is another question.

Leave a Reply