Jessie and Kirk Dawson were in their late 20’s when they I moved into Grove Glen, and Fred Glover’s wife Eva saw at once that they needed work. This was a tight community, not the kind two kids could walk into cold, so Eva took it as her responsibility. She was, after all, the boss’s wife. She invited herself and Fred over for the inspection tour (“theater seats, how spunky“), after which she invited Kirk to offer them drinks.

Then Eva sat on the raw terrace outside the half-finished house, crossing her sleek, waxed legs and giving advice in a whiskey voice.

“Children. If you want to be invited, you’ll have to entertain. When we were getting started Fred and I used to give huge bashes four times a year.” She looked over at Fred, who was busy numbering the available kinds of ground cover for Kirk. “Didn’t we, Fred?”

Fred did not so much answer as hum, a little buzz that might have been a tribute to the waning summer, their long lives together, the shift of light that warned of approaching fall. “Most people around here go in for organic gardening,” he went on telling Kirk. “Garlic instead of pesticides. Bags of human hair.”

“You’d look so much prettier with contact lenses,” Eva told Jessie. “You don’t have to go around looking like a schoolteacher.” In the next breath she cautioned: “Never outdress your guests.”

“But it’s the first time I’ve been able to afford decent clothes.”

“Sweetie, you’re already one up on us. You’re young.”

Jessie saw that the tan, the elegant linen shorts, the silk shirt were carefully put together to distract from the lines in Eva’s face, beginning rings around her neck. “I’m sorry.”

Eva said to Fred, “Aren’t they adorable?”

Jessie murmured, “Lord!”

But Fred was showing Kirk how to drown slugs in dishes of beer.

“It’s not your fault you’re young,” Eva said, putting on maturity like a badge; she seemed so seasoned! “These days I shudder every time I see the first red leaf.”

Fred smiled indulgently. “Eva, I think these kids have had enough of us for now.”

“Oh no,” Kirk said in haste.

But Jessie was protesting. “Kids!”

“Shh,” Eva said in a there-there tone. “Shh.”

She couldn’t help it if she and Kirk were the youngest couple here. He looked like a stripling next to the others with their grave expressions and their substantial adult silhouettes. Their solidity made Kirk seem slight and unsteady as a setter puppy, who could demolish small objects with a single wag of the tail. All this, Fred explained, was the result of conscious effort: “Who wants to do business with a young guy?” The women had a sheen Jessie envied; they were so far ahead that it gave her the feeling she was running along behind, calling after them: Wait up!

Two months ago Kirk and Jessie were sitting around on mattresses in student apartments; now they were here. Jessie put on stockings and high heels to teach; Kirk moved into dark suits and sober ties. Colliding in front of the hall mirror, they had to laugh. They even had a mortgage now. The realtor had halted them in the middle of the newly sodded front lawn to point out the potential for upgrading. In time they would leave their cookie-cutter split level for one of the architects’ houses perched on Presidents’ Hill.

The people on the hill threw the best parties. Everybody said so. Fred and Eva gave supper dances in their lofty box with its swastika of porches, with taped music drifting out over the tops of the trees. Howard Patterson, who ran the bank, preferred gourmet dinners for twelve; she cooked but he whipped into the kitchen at the last minute to make zabaglione for dessert. Larry the ophthalmologist and his wife Cindy liked to have guests for cocktails and supper around the pool even after it was too late in the season to sit outside without coats. Archie Leverett held what he called massive retaliations—an even hundred invited for buffet, with nothing but booze and finger sandwiches. He did it to renew his credit, he said—one bash and he could eat out every night of the year.

It was balding, funny-looking Archie who took Kirk and Jessie in hand, slouching at their kitchen table like just another kid. He was an excellent guest, an unexpected third for dinner, always welcome because he was wicked and paid for their kindness with community secrets none of the others would admit. Once or twice when he was sitting at their table Jessie saw blue patches under his eyes and guessed at his level of exhaustion: not easy to have to sing for your supper every single night.

“My dears,” he said to Jessie and Kirk, “watch out for Anthony, he flits from flower to flower, and you never know whether you’re a flower or not.”

He defined the territory and identified the seasons: “You’d better know, we’re in a year of dancing and petty flirtation. Have fun but don’t get hurt.”

Wait a minute, Jessie thought. We’re not even all grown up.

Still, being invited was better than not being invited. If they went out often enough people might get used to them. Being on the inside was always better than being on the outside; it was always better to belong. She liked going to the store for the Sunday papers to discover neighbors drifting in like convalescents, redolent of the night before, disabled veterans of last night’s party comparing notes. What pleasures had they shared; what secrets did they know? It was not so much troubling as sad to leave the movies on a quiet Saturday night and discover the rest of the world was at somebody’s party—fleets of cars parked in front of Fred and Eva’s house. Everybody’s there, she’d say mournfully, not knowing quite who everybody was.

The parties weren’t all that good, really; the best moment always came in front of the hall mirror as she and Kirk prepared expressions to wear when they went out. But exclusion hurt, and Jessie nursed the suspicion that there were better times available; once she and Kirk were accepted life here would open like a rose.

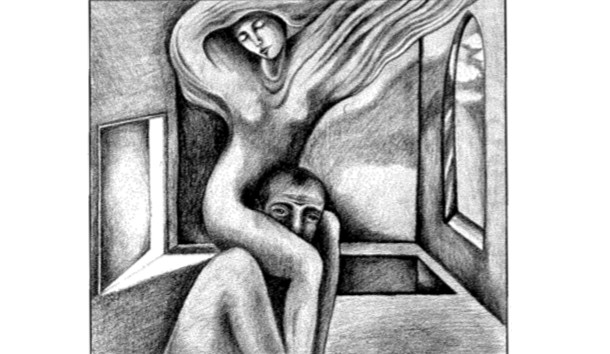

They were invited more often, but had they been accepted? It was hard to know. When a party took off without them Jessie looked at Kirk with raccoon eyes: Maybe they forgot. He told her not to brood, these people weren’t worth it, and she said, I know, I know. Still she imagined crunching through the bushes outside those parties to scratch on one of the glowing windows, those assembled turning in varying degrees of shock as she climbed over the sill and presented herself with an ingratiating cartoon grin. Listen, we’re really terrific people, just give us a chance.

“Your time will come,” Archie said, smiling ingenuously. His salt-and-pepper hair was rumpled like a boy’s. He appeared regularly on Thursdays now because he knew Jessie got off early and liked to cook all afternoon. Because he had no household, he was welcome in all the houses: friend, brother, spare man, potential romance but potential only, which extended the possibilities into infinity; in his own strange way he was also ageless, with no wife to weigh him down and no children growing up, yardsticks measuring him off. “Don’t worry,” he said kindly, “You’re so new they haven’t found out about you; it’s almost your turn to be picked up and twirled around.”

Kirk said, “Do we want that?”

“Everybody wants to be a flower at least some of the time.” Archie cast a judgmental look around the kitchen. “You’re about ready. Let’s help things along. You’re giving a cocktail party the Sunday after Thanksgiving,” he said. “Dinners are so treacherous. You can kill yourself making the perfect food and lose it all with the wrong guest mix. Now cocktails. Cocktails are safe.”

“Safe?”

“People don’t stay around long enough to get into trouble,” Archie said.

Jessie felt like a child in her pajamas watching the grown-ups from the top of the stairs. “Oh Archie, maybe that’s what we want.”

He shook his head. “When it gets too late people’s fangs begin to show.”

“You’re making it up.”

“Even a man who says his prayers . . . Listen, it’s like the full moon in werewolf country; you don’t want to be around.”

Inside her something was teetering. “Maybe we do.”

“Not yet,” he said. “Not until you’re stronger. You don’t want to end up getting hurt.”

Kirk said, “Maybe you’d better listen to the wisdom of our native beater.”

“Both of you, stop.”

So Archie helped them make up the list, providing pocket biographies as he went. “Bob Shortell’s secret is that he was called Piggy in college; he’s in shape now but you can see the stretch marks if you catch him in a bathing suit.” “Cindy and Larry went to Rio for plastic surgery—a nip here, a tuck there—they cut off anything that flops.” “Lester Hancock has cancer but it’s a secret; left testicle.” “Howard never got over the girl he loved in college; she went to the ladies’ room at the top of the Bailey building and dropped like a stone.”

“That’s very sad.”

“It explains a lot of things.”

While Jessie fed on it, gossip made Kirk uneasy. “I suppose you’re going to tell me everybody has some terrible secret, even Fred and Eva.”

“After a certain age, no one is safe.”

Jessie started; something had changed in the room; looking at Archie now in the strong overhead light she saw that he had not changed but his aura was changing; there was a disturbance in the air behind him, as if of the shifting of large shapes; he was—sick? In danger? She did not know. It was as if behind him, the abyss was opening—had always been there. “Oh, Archie,” she cried.

His eyes widened: What? What is it? What?

Alarmed, she plunged in after him, bent on retrieval. “You’re not old!” she cried.

Archie blinked; the shadows faded. He grinned that boy grin. “Certainly not. What’s all the fuss about?”

Their party was a grand success. The others all came in their autumn best, men and women in rusty tweeds and brilliant colors, everybody delighted to be at a party on this long weekend that usually died on Friday night because everybody assumed that everybody else had planned. Because Kirk and Jessie were new everybody behaved well, and if the outlines of their bodies were beginning to blur or the skin of their faces softened, forming new folds, still they talked and laughed with conviction; Jessie remembers wondering on too many nights, Where is everybody? Her heart bounced:

Everybody is here.

Everybody got pleasantly buzzed but not messy and, in a spirit of solidarity, Fred let it drop that if the kids knew where they could get a joint he’d love to smoke. When the party was over everybody spilled out onto the sidewalk laughing, chattering in the black late afternoon. Several clumped to go to restaurants and others asked friends to pickup suppers at home.

Archie lingered in the living room, which was unnaturally silent and still blue with smoke, beginning to smell sour. “Bless you, my children, it is accomplished. Now you’re on everybody’s list.”

Jessie offered, because he’d expect it, “Stay for supper. We’re not cleaning up until tomorrow, I promise.”

“Thanks, but I have a better offer,” he said, looking rumpled but game. “The Glovers are burning steaks.”

The tempo quickened in December. There was such a spasm of festivity that Jessie began to complain. She and Kirk had slid from too much staying in to too much going out, sleeping late after Friday’s party, convalescing Saturdays so they’d be ready for the party that night. Jessie found herself looking forward to the stilly fastness of January, when she and Kirk could be snowed in.

Archie had them to that year’s massive retaliation, which was followed by parties at the Stoners’ and the Shortells’. If there was an urgency to the pace, fueled by Lester Hancock’s physical decline, Kirk and Jessie would not see it because they hardly knew Lester and were so new at life that they didn’t recognize the signs. People began being discovered in alarming situations: public drunkenness, illicit grapplings.

Sunspots, Archie said. It happened every few years. When the storm windows came off in the spring and they got cut out of their winter underwear there would be a few surprises, he said.

Jessie and Kirk clung together for mutual protection. If she lost track of him at some big party she knew she’d find him backed into the refrigerator or cornered in some candle-lit alcove, signaling over some predatory woman’s head with his teeth bared in a desperate grin. She’d spring to the rescue, even as he was pledged to keep track and rescue her.

“Bob Shortell is Kirk’s new boss, you know,” Eva said over the Sunday paper rack.

Remembering how she yearned to be part of these conversations, Jessie caught herself thinking: Is this all? “I thought Fred was.”

“Bob’s been moved in. He thinks you don’t like him.”

“That letch?”

“Honey, it wouldn’t cost you anything to flirt with him.”

“Is that what that was?” “Think of it as a form of flattery.”

“I think it’s creepy,” Jessie said. What she meant was: But he’s old.

It seemed best to stay out of his way. Dancing, she and Kirk danced together best, danced to safety as lightly as they could. Except they could not quit blundering into unexpected couples: Bob and the vet’s new wife slow-dancing in the bathroom; feisty Howard mumbling with his hand balled in the soft spot in Eva’s neck; skinny Lester Hancock hugging Beth with intense concentration, as if his life depended on it. Going home, Jessie and Kirk would ask each other: Are we going to be like that? No. How could they? It was tacit. They would never. No.

Bob Shortell’s diagnosis was made the day before Fred and Eva’s Christmas supper dance; he was getting the news from his physician around the time Beth took Howard to the emergency room with chest pains. And Lester—poor Lester might not be well enough to come.

The party had been scheduled for months; Fred and Eva had hired a live band this time and after agonized consultation with most of the guest list, they decided it would be silly and wasteful not to go ahead. It’s what Howard and poor Lester would want, and what Bob Shortell needed, or so they said. When a small delegation stopped by the hospital on the way to the party with flowers and a silver shaker of Martinis for Howard, Beth met them in the hall with tears in her eyes and said Howard couldn’t see them right now. She knew he’d appreciate everybody coming like this, and they’d both be thinking of everybody at the party thinking of them.

By the time Jessie and Kirk got to Fred and Eva’s party there was a thin crust of snow silvering the hillside and light crashed out of all the windows, making every surface glitter. She and Kirk could hear the music even from here; there were people dancing on the porches in spite of the cold. Jessie had a new dress that rode over her body in a silky sweep, and her legs felt sleek and strong in the icy pantyhose; she could not have said precisely why she was so conscious of her body tonight, its youth, her health, but as she and Kirk went inside she put it before her like a shield.

This was the biggest party of the year, and everybody here seemed to have gotten a head start, from Cindy, who was sitting on several men’s laps at once, which she usually did only after midnight, to Bob, who could not stop running his knuckles down the V in the new law clerk’s satin dress. There was a surprising-looking person on the sofa in a white suit and pointed shoes; he could have come straight out of a foreign movie, or downtown Algiers. He listened to Eva babble with a bright, feral, uncomprehending grin. Some people were already unsteady on their feet and the edges of Eva’s hors d’oeuvres had begun to curl. Jessie and Kirk picked up drinks quickly, with the sense that once again the party had left without them: Wait up! Then they fell into a dance, bodies matching perfectly, whirling in the illusion of escape.

Here was Lester after all; when he cut in Jessie turned dutifully but reluctantly, readjusting her steps as he waltzed her away with fevered grace.

“You know,” he said, when he finally said anything, “I’m donating my organs to Harvard.”

“Oh Lester, it’s much too early to think about that.” It was not. She outweighed Lester now.

“That is, if they’ll take them.” His hold was so light that his bones must have been hollow, like a bird’s. “I’d be honored if you’d witness this.”

“Of course,” she said, “but that won’t be for years.”

He’d let her go and was fumbling in his pocket. “I’ve brought along the instrument.”

So she sat soberly in a little knot with Fred and Kirk and a woman she didn’t know while Lester filled in the appropriate blanks and signed, and made them sign.

When Lester stashed the document and Fred pulled her up to dance, Jessie was relieved: good old Fred. She had to keep moving. Larry and Cindy were fighting in one corner while the vet’s wife cried all by herself in another, and in the alcove the less aggressive halves of two couples were clinging for dear life. Barbara Shortell, who was getting fat, hunched over the buffet, shoving fruitcake into her mouth. All this, and it wasn’t even ten o’clock. In the library where Fred took her when the piece ended, people clumped around the fireplace, gathering around the flames as if to ward off wolves, or whatever it was that waited outside, stalking in the dark.

Fred startled her, finishing a sentence she hadn’t even heard. “Pubic hair.”

“What?”

“All the way up to her navel. Amazing. How far up is yours?”

“I was wondering why Lester brought that to the party,” she said too quickly, disturbed. “A living will.”

Bob Shortell slid into the circle on her other side. “You’re much too young to understand.”

“Oh Lester’s just on the rag,” Fred said. “All he has left to think about. You know he isn’t getting any.”

“But it’s cancer!”

“His wife thinks it’s AIDS. So much for sex.”

In the shadows somebody said, sotto voce, “He’s not the only one.”

“Poor Howard, when he gets out he’ll have to keep his prick in a sling, you know how heart patients are.”

“Not me,” Bob said, weaving a spell to keep away dark powers.

“Not me,” Fred said.

From the darkness, somebody else completed the charm, saying bluffly, “Not me.”

Jessie would not wait to find out who it was that asked, as she wheeled and fled them, “What about you? I bet you’re getting enough,” nor would she know who said disgustedly, “Kids. Kids always get enough.”

She wanted not to cry. I’m not a kid.

She went looking for Kirk with a sense of panic, beating her way through the thicket of dancers and locking on to him like a heat-seeking missile. His arm went up to encircle her and when she quit shaking they began to dance, which they did until Spink, she thought it was, tried to cut in and she dragged Kirk out onto one of the porches, hoarse with desperation, whispering, “What’s the matter with everybody, what’s the matter with everybody?”

“It’s just their way of communicating,” Kirk said without having to ask.

“It’s so sad.” It was. She’d always envied these people their assurance and maturity, their style, the fact that they could accept or exclude at will, but at what price? Something had happened to these people between the time when they moved to this place as kids themselves and now, and she could not for the life of her figure out what. All she could see was the way they looked at the end of these parties, all these dressed-up people with their drawn faces and smirched mouths and their evening spoiled by emotional exhaustion and too much drink. How high were their hopes when they set out tonight and what’s happened to them between then and now? What terrible misfortune has befallen them? “I wish they could just be happy and have a good time.”

Kirk said, “That’s what they’re trying to do.”

“Well it isn’t working,” she said mournfully.

“Don’t you think they want it to work?” He crunched her flowers, hugging her. “Oh honey, Howard is very bad. Beth just called.” He pulled her back to the dance floor. “Poor Beth.”

“Oh, poor everybody,” she cried, but she could not get over the way so many people could aim for one mark and hit another, or how sad it was. Bereft, she clung to Kirk and whirled in the beginning understanding that they had been set down at the beginning of the first mile of a long road, on a journey she could not bear to contemplate. “Please don’t let us end up like that.”

Blindly, Kirk promised. “We’ll never end up like that.”

She was gulping air. “I have to get out of here.”

Which was how they happened upon Archie and Eva, half-dressed and tangled in Eva’s mop corner next to the back door, the two of them clinging in spite of Fred and the presence of Archie’s beau in his white suit, marooned on the living room sofa while Archie tried to recapture something here; he looked at them over Eva’s head with a rueful twinkle as they gasped and tried to back out.

“I tried to tell you,” Archie said.

“W-we were just wondering about poor Howard.”

Then Eva—her friend! turned and lashed out at her. “You! Fools! What do you care? You’re young.”

As they fled they could hear her spitting, driving them out with a fervor that sped them into the darkness, choking on nervous laughter. They heard Eva railing: “You. You think you are so holy, just like all the saints and popes!”

And the mitigating, or were they spiteful words of Archie, following: “Hush, sweetness. Don’t worry. They won’t be young for long.”

Leave a Reply