For the last several years Texas farmers and ranchers whose lands butt up against the Rio Grande have complained about cross-border raids by thugs of Mexican drug cartels. “It’s a war. Make no mistake about it,” said Texas Agriculture Commissioner Todd Staples. “And it’s happening on American soil.” Staples thinks the bountiful productivity of the Rio Grande Valley could go into decline and affect our food supply. “Farmers and ranchers,” he remarked, “are being run off their own property by armed terrorists showing up and telling them they have to leave their land.” His official website, ProtectYourTexasBorder.com, is full of such harrowing stories. In a formal declaration on the site he says something that should be dear to the hearts of true conservatives: “America’s war on terrorism has sent thousands of troops overseas, but the reality is, there is a growing threat here at home. . . . Until Washington stands beside us, Texas is prepared to take matters into its own hands to the fullest extent possible.”

Plagued with similar cross-border raids during the 1870’s, Texas did take matters into its own hands—in the person of Lee McNelly. An independently minded Texas Ranger, McNelly did what the federal government should have done and crossed the border into Mexico.

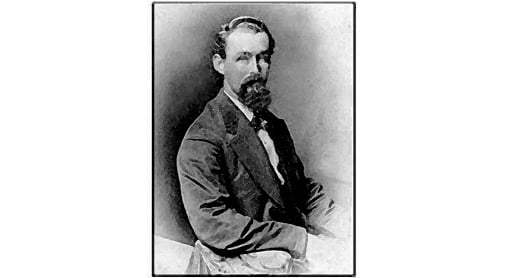

Born in 1844, McNelly began his life in what would become the northernmost portion of the panhandle of West Virginia, an area just west of Pittsburgh and more Pennsylvania than Virginia. He was the son of P.J. McNelly and his wife, the former Mary Downey. His older siblings had been born in Ireland before the family immigrated to America. McNelly contracted tuberculosis at the age of 8, and in 1860, when he was 16, the family moved to Texas, hoping that the climate would improve his condition. The McNellys settled on a farm west of Brenham, about halfway between Houston and Austin.

A day after his 17th birthday McNelly enlisted in the Confederate Army and would serve in the Texas Mounted Volunteers. His service as a scout and in battles was brilliant and heroic, and only three months past his 19th birthday he was made a commissioned officer. His leadership and tactical sense were unsurpassed. At one point, with no more than 100 men in his command, he outmaneuvered, surprised, and captured 800 Union troops. In April 1864, after three years of continual fighting, he was seriously wounded for the first time and took his first extended leave to recover. Within a few months he was back in the saddle—now promoted to captain—and continued fighting until the end of the war.

Following the cessation of hostilities, McNelly married and settled on a farm near his family’s home in Washington County. Like other Texans, McNelly chafed at the authority of Union troops and Reconstruction rule. In 1870, Texans were allowed a limited degree of law-enforcement authority with the organization of the State Police. McNelly was so respected that he was asked to serve as one of the four captains of the force. Despite some misgivings about the political nature of the State Police, he accepted his commission. He suffered a gunshot wound while on duty in 1871 but continued serving until the force was disbanded in 1874. He was one of the few veterans of the notoriously corrupt State Police who concluded his service with a clean reputation.

To replace the State Police the state legislature reconstituted the Texas Rangers, which the Reconstruction government had not allowed to reorganize following the Civil War. McNelly was appointed commander of the Ranger Special Force and tasked with bringing law and order to the Nueces Strip, a kind of no man’s land between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers in southwest Texas. The Strip was raided, almost at will, by various Mexican banditos, especially Juan Cortina, who was the alcalde of Matamoros, the Mexican military commander for the Rio Grande frontier, and the scion of a family who controlled a 260,000-acre land grant. During the Mexican War, he had served as a general. Cortina considered raids across the Rio Grande as guerrilla warfare against the hated gringos.

Before McNelly could go after Cortina and other banditos, though, the Sutton-Taylor feud reignited in DeWitt County. The feud had waxed and waned since it first erupted in 1866. It was the longest and bloodiest feud in the history of Texas and involved several notable gunfighters, including John Wesley Hardin. McNelly led his company of 40 Rangers into DeWitt County and remained for four months until peace was restored.

In 1875 McNelly moved against the Mexican banditos. It was no mean undertaking. Juan Cortina had a force of no fewer than 2,000 men and, farther up the Rio Grande, Juan Flores Salinas could mobilize 500. Salinas was not only a bandito but also the alcalde of Camargo and the commander of the local Mexican militia, holding the rank of general. Cortina was ruthless and murderous, and Salinas more so. For years they had crossed the Rio Grande into Texas and had stolen cattle and horses, and pillaged towns. Entire ranch families were murdered, women and girls raped, and men tortured, including by burning them alive. Then, as quickly as the banditos came, they were back across the Rio Grande and untouchable in Mexico. McNelly knew he could not wage war successfully against these two bandit leaders without ignoring both Texas and federal law. Most of all, he would have to cross the border into Mexico and strike at these banditos in their sanctuaries. His Rangers would follow him anywhere. They called themselves “Little McNellys.”

By 1875 McNelly himself had become a little McNelly. Tuberculosis was ravaging his body, and at 5’7″ he weighed less than 130 lbs. His hair was still reddish brown and his eyes brilliant blue, but his voice had become reed thin, and he could barely speak above a hoarse whisper.

After routing various bands of banditos, including a Cortina raiding party, and recovering thousands of head of cattle during the spring and summer of 1875, McNelly made a move that reverberated all the way to Washington, D.C. During this time, he was working closely with the great cattle baron of southwest Texas, Richard King. Also the son of Irish immigrants, King had risen from orphan child in New York City to ship captain, to U.S. Navy captain during the Mexican War, to Gulf Coast shipper and trader, to Confederate blockade runner during the Civil War—a real-life Rhett Butler—to owner of the huge King Ranch. His vast holdings suffered again and again from the raids of the banditos. His ranch became an unofficial headquarters for McNelly and his Rangers. At his own expense, King supplied McNelly with the best horses that could be found in Texas, as well as rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition.

The rifles were Winchester’s latest and best to date, the Model 1873, which would be called “The gun that won the West.” The Model ’73 was a .44 caliber, lever-action repeater, like earlier Winchesters, but was the first to use a metallic center-fire cartridge. This allowed the cartridge to be packed with 40 grains of black powder, not only making the ’73 more powerful than earlier models but also giving rise to another commonly used name for the rifle, the “.44-40.” The version of the Model ’73 supplied to McNelly was the carbine, its shorter 20″ barrel better suited for work on horseback.

In November 1875 McNelly led 28 Rangers to the latest hot spot, a stretch of the Rio Grande near Rio Grande City and the Ringgold Barracks, home to American soldiers of the 24th Infantry and the 8th Cavalry. McNelly arrived to find the Army watching helplessly as several hundred head of cattle—stolen from Texas ranches—were being driven by the Salinas gang across the Rio Grande and into Mexico. McNelly told his Rangers, “I’m going to bring those beeves back to Texas. I can’t order a single one of you men to go with me but I sure need you—every one who’ll volunteer.” An Army officer told McNelly he would be breaking two laws: the first for mounting an armed invasion of a foreign country, and the second for committing suicide.

During the night of November 18-19, 1875, McNelly stealthily crossed into Mexico. Shortly after dawn, he and his Rangers came upon an outlying camp on Salinas’s Rancho Las Cuevas. A guard opened fire, but McNelly dropped him with a revolver shot. Two-dozen other Mexicans poured out of adobe buildings into the foggy morning air. Although several Rangers had rounds narrowly miss them, it was a turkey shoot for the Texans. When the firing stopped, all the Mexican banditos lay dead.

While the short gun battle raged, a Mexican woman inexplicably continued making tortillas as if nothing unusual were happening. She seemed unaffected by the shooting and, when questioned, told the Rangers that Salinas’s headquarters were at the main ranch further on. Worried that the element of surprise was now lost, McNelly pushed his boys as fast as possible. They soon came upon a cluster of abode buildings, enclosed on two sides by a six-foot wall, and a chapel, and several corrals. To their astonishment, all of Salinas’s men seemed to be going about their normal morning tasks without any sense of urgency.

Soon, a column of men rode out of the compound. From concealed positions, McNelly and his Rangers opened fire. Their accurate shooting dropped a dozen or more banditos from their saddles and sent several dozen more, some badly wounded, galloping back to the compound. Within minutes, though, the Rangers found themselves engaged with some 350 more of Salinas’s men. After a blistering gun battle, McNelly withdrew in good order to the Rio Grande. Instead of crossing to the American bank, he had his men dig in—on Mexican soil.

Meanwhile, Salinas’s force was growing, now numbering well more than 500 men. The Mexicans indicated they wanted to parlay. McNelly and two of his officers walked out under a white flag and met General Salinas and several of his subordinate officers. Salinas told McNelly that his situation was hopeless and he must surrender immediately or face annihilation. This would be the Alamo all over again. McNelly replied, “You have two hours to return all stolen cattle. If not, then I attack.”

General Salinas was outraged. As soon as McNelly returned to his Rangers, Salinas, several of his officers, and some 200 of his men mounted horses and charged. The Rangers, crack shots one and all, began picking off the Mexicans at long distance. Dozens were killed or wounded, including Salinas, who was blown out of his saddle and died on the spot. The charge faltered, then broke.

By then, Lt. Col. James F. Randlett had positioned elements of the 24th Infantry and the 8th Cavalry on the American side of the Rio Grande. Some came across the river but only to tell McNelly to return to American soil. McNelly said he would do so only when the Mexicans returned the stolen cattle. Later in the day the Mexican forces again tried to dislodge McNelly but again failed and suffered numerous casualties.

By now the telegraph was buzzing with activity, and soldiers were continually relaying messages to McNelly. Maj. Andrew J. Alexander arrived with a message from Col. Joseph Potter at Fort Brown, located on the Rio Grande at Brownsville:

Advise Captain McNelly to return at once to this side of the river. Inform him that you are directed not to support him in any way while he remains on Mexican territory. If McNelly is attacked by Mexican forces on Mexican soil, do not render him any assistance. Let me know if McNelly acts on this advice.

McNelly read the telegram and told Alexander, “The answer is no.”

At sundown Major Alexander arrived with a second telegram he received from Colonel Potter: “Secretary of War Belknap orders you to demand McNelly return at once to Texas. Do not support him in any manner. Inform the Secretary if McNelly acts on these orders and returns to Texas.” McNelly carefully wrote out a reply so there would be no mistaking his intentions: “Near Las Cuevas, Mexico, Nov. 20, 1875. I shall remain in Mexico with my rangers and cross back at my discretion. Give my compliments to the Secretary of War and tell him and his United States soldiers to go to Hell. Signed, Lee H. McNelly, commanding.”

The next morning, McNelly opened negotiations with the Mexicans who, having lost General Salinas and several other officers and men, promised to return the stolen cattle if McNelly and his Rangers would withdraw. The Texans watched as the cattle began arriving, driven by vaqueros into a corral at the Camargo crossing, directly across from Ringgold Barracks and Rio Grande City. The Mexicans said the cattle would be driven across the river shortly after McNelly fulfilled his end of the bargain. McNelly soon had his boys back on American soil and allowed them to lounge about in Rio Grande City.

By three o’clock in the afternoon and with the Mexicans having not yet returned any cattle, McNelly decided he had to take action. With no more than a dozen of his Rangers he again crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico. The small force was called the Death Squad, not because townsfolk in Rio Grande City thought the band would kill Mexicans but because they reckoned that McNelly and the others would never return.

On the Mexican side, McNelly found five uniformed and armed customs officers waiting for them. More than a dozen vaqueros were some distance away at the corral. Through Ranger Tom Sullivan, who was fluent in Spanish, McNelly told the commanding officer, a captain, that the cattle were long overdue for delivery to Texas. The captain said that the cattle couldn’t leave until they had been inspected. McNelly replied that they had been stolen without being inspected and could be returned the same way. The customs captain then said that it was Sunday and that no such business could be transacted. Sensing the stall was on, McNelly, in a lightning-quick move, drew his revolver and clubbed the captain on the side of his head. As the customs officer fell to the ground, McNelly kneed him in the belly. At the same time McNelly’s boys drew their guns. One of the Mexicans managed to draw his gun before he was shot. The others quickly surrendered.

The Rangers jerked the stunned customs captain to his feet, and McNelly told him that he and the other customs officers would be taken across the river and shot if the cattle didn’t start moving. Although groggy and in pain, the Mexican captain started barking orders. The vaqueros sprang into action, perhaps equally motivated by the Rangers’ guns, trained on them as well as on the customs officers.

Within an hour, some 400 cattle were driven across the Rio Grande. The U.S. Army watched in amazement. The cattle carried the brand of nearly every ranch in the Nueces Strip, including the “Running W” of the King Ranch.

Mightily impressed by what McNelly had done but not wanting to be identified with him, the Army officers from Ringgold Barracks tried to distance themselves. Washington publicly condemned McNelly’s raid but did nothing to punish him. In Texas, he was treated as a hero. He continued to serve as commander of the Special Force until he succumbed to tuberculosis in 1877.

Leave a Reply