Last night we watched from the hotel terrace as a giant cargo ship cast anchor in the Tyrrhenian indigo and proceeded to unload fresh water for the whole of our sunburnt island, an enterprise which from that vantage point seemed a triumph of technology over nature. A moment’s reflection, however, would have neatly reversed the argument, suggesting that the economic elites of Europe vacationing in the Aeolian Islands had come here craving nature’s apotheosis and technology’s undoing.

What we have here is a reversal of polarities by now so familiar it is no longer an isolated anomaly. It is rather a kind of systemic schizophrenia, which has taken hold of the world we consider First—in contrast to the Second and Third Worlds, almost universally regarded as unambiguously in need of reason’s ministrations. Needless to say, that is so because a vast majority of people with both the inclination and the leisure to linger on the terraces of expensive hotels and to ponder equally dear ethical dilemmas hail from that schizophrenic First World. They have long decided what’s best for others and can now afford the luxury of doubting what’s best for themselves.

Given the choice, men in suits crave to be Tarzans. It is worth noting that the Edgar Rice Burroughs classic hit the bookshops simultaneously with the opening salvos of World War I, an unprecedented calamity that demonstrated to many the failure of mankind—particularly of its reason, that is to say, of European science and technology—to manage the universe they had received in trust upon the death of their God. Having consigned such aspects of human irrationality as faith, hope, and love to the rubbish bin of history, man was left a quattro occhi with the airplanes, machine guns, and mills that now all of a sudden turned satanic on him—satanic not as in William Blake’s visionary simile, but as in a literal truth, one bitter to the tongue and redolent of the poison gas chlorine. Within a decade even an incurable optimist might agree that had it not been preceded by maiming of truly apocalyptic proportions, man’s discovery of penicillin would not have been as dramatic. Was science only good for undoing the damage science had done?

The subsequent decade saw the Bolsheviks enthroned and the Nazis, in their turn, on the brink of kingship, and although the former were indeed men of reason—which they advertised as “dialectical materialism”—while the latter represented a political reaction, advertising their brand of totalitarianism as a return to ancient values and forgotten gods, both were one in their total reliance on the instruments of mass persuasion whose very existence was unthinkable without the primacy of science. Once again Tarzan’s way seemed the humanist alternative to the ongoing carnage.

So it seems to this day to the men in suits, who come to the island of Panarea to get away from it all. A holiday, in our culture, is the only moment in the nominally Christian calendar when we seem to value the things that are literally holy—before returning to the satanic mills, companies, and banks that work around the clock to bury those blessed things ever deeper, to make them ever more unobtainable, to all but displace them from the ordinary currents of human existence. They are like fresh water on a parched island, available only to those who have become rich by denying it to the rest.

And yet the Tarzan way is not the trope of a solution, but an allotrope of the problem. Last year I reviewed in these pages a new book by Nicholas Carr detailing the regression of the modern brain away from the linearity that has characterized human thinking throughout civilization. On the strength of the book’s scientific evidence it was to Tarzan that I compared modern man, arguing that the chief achievement of civilization was man’s ability to set the agenda of his own thought—in stark contrast to the primitive man, whose thinking agenda was set by nature, or the modern man, whose thinking agenda is set by the technology that has all but supplanted nature. And in the world we call developed or advanced, that First World where fresh water is always on tap but you can’t find a faithful wife, a good friend, or a real tomato, modern technology is practically synonymous with computer, just as literacy rarely means more that computer literacy.

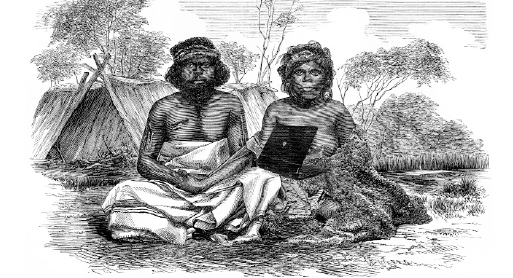

In my essay I noted that our ancestors, who lived in the forest, never had a moment’s peace. The forest would speak to those poor Tarzans, order them about, punish and reward them from dawn to dusk. Every roll of the stone, every crack of the bough, and every bird cry had a meaning, and the meaning was largely binary, signifying either danger or opportunity. All the signals, moreover, came all at once, in a swarm of portents that had to be identified, interpreted, and acted upon.

Thus regarded from the hotel terrace, civilization was, above all, leisure for reflection—something that Burroughs’ hero only had as Lord Greystoke. Regarded in this way, civilization was time for deliberation distinguished by linearity. History, prophecy, and speech were all born of that patient effort, as it is impossible to project a future event without analyzing the past, or without having recourse to something like syntax. Whereas before it had been the chaos of the forest that determined his thinking, man was now in control of his thought, setting himself subjects for ratiocination and arriving at logical conclusions.

Millennia later, that linear world was man’s unique habitation. Almost everything he thought and did had an if and a then as points of departure, deliberately positioned on the same ratiocinative plane. Syllogism and syntax, map and book, mathematics and medicine, factory and mill—as well as such plainly satanic instruments of mass persuasion as the machine gun and the airplane that eventually secured for the more linear-minded peoples of the world dominance over the less linear-minded—none of this would have been possible without the will and the time to think things through. Tarzan would have remained Tarzan in a jungle full of similar beings.

Increasingly, it looks like technology has restored man to his aboriginal state. The difference is that instead of the forest, alive with real danger and real opportunity, the chaos now shaping the modern Tarzan’s mind offers no individual opportunity to speak of and only a collective notion of danger. The neurological implications of “connectivity,” the hyperalert but quasi-animal state in which much of mankind now passes its days and nights, add up to a physiological revolution. Like all revolutions, it is reactionary and regressive.

Carr notes that it is not unusual for an office worker, the hunter-gatherer of our day, “to glance at his in-box thirty or forty times an hour,” just as his ancestor would at the dark bower that he had not dared to explore. Hypermedia, introduced by internet companies to keep his attention, overthrows “the patriarchal authority of the author,” fragmenting what it pretends to keep. Social networks bombard their hundreds of millions of members with “a never-ending ‘stream’ of ‘real-time updates,’ brief messages about, as a Twitter slogan puts it, ‘what’s happening right now.’”

In most countries “people spend, on average, between nineteen and twenty-seven seconds looking at a page before moving on to the next one, including the time required for the page to load.” In fact, “it almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.” From “the myriad visual clues that flash across our retinas as we navigate the online world” there is no escape, no reprieve, not even a nanosecond’s pause. It “turns us into lab rats constantly pressing levers,” yet congratulating ourselves on our achievement the way primitive man—or the lab rat—never did.

Not everybody shares my sarcasm, of course. Daniel Pink, author of a bestselling book entitled A Whole New Mind: Moving From the Information Age to the Conceptual Age, writes that, “for nearly a century, Western society in general, and American society in particular, has been dominated by a form of thinking and an approach to life that is narrowly reductive and analytical.” So enthusiastic is this pundit about the change that has overcome mankind that I swiftly recognize in him yet another in the long line of Edgar Rice Burroughses who have come to us in the wake of the Great War original. Seeing in the atrophy of linearity a liberation—“gone is the age of ‘left-brain’ dominance,” exults the cover blurb of the book—Pink heaps praises upon the new man like himself, unable to comprehend, or indeed to compose, a grammatical sentence, yet rich in the qualities of “inventiveness, empathy, joyfulness” that might well have been dreamed up to describe the fictional Tarzan.

Epigones of Burroughs like Pink have produced, in their turn, numerous epigones, acolytes, or cheerleaders, few of them disinterested. A manual for “IT leaders,” for instance, salivates at the wisdom of the filmmaker George Lucas, who was asked, “What do students need to be learning that they’re not?” He answered,

They need to understand a new language of expression. The way we are educating is based on 19th-century ideas and methods. Here we are, entering the 21st century, and you look at our schools and ask, “Why are we doing things in this ancient way?” Our system of education is locked in a time capsule. You want to say to the people in charge, “You’re not using today’s tools! Wake up!”

The wisdom of Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, which Lucas appears to have plagiarized, is equally delicious. Our high schools, opines Gates, “cannot teach our kids what they need to know today. Our high schools were designed fifty years ago to meet the needs of another age. Until we design them to meet the needs of the 21st century, we will keep limiting—even ruining—the lives of millions of Americans every year.”

As Pink himself tells an interviewer,

Your ability to draw on right-brain skills has become much more important. For instance, I think that design has become a fundamental literacy in business. . . . Whether it’s industrial design, graphic design, environmental design, or even fashion design, a good consultant must be literate in that now to go into an organization and offer useful advice.

Nauseating as such gobbledygook—banal, derivative, what England’s Private Eye calls “Pseud’s Corner” philosophizing, yet so transparently corporatist in outlook—may seem at first glance, a few moments’ reflection on that hotel terrace high above the Tyrrhenian Sea will once again make havoc of these knee-jerk reactions. For what the fashionably hip soothsayer is saying about the modern Tarzan and his newfound illiteracy—known henceforth as 21st-century literacy—is exactly what Carr is saying, with the difference that in Pink’s case the polarities are reversed, and he thrills where Carr and I shake with disgust and fear.

Accordingly, “I propose four reasons for the need to change to a new form of literacy,” writes the author of the “IT leaders” manual. Here is the first of these thrilling reasons:

By the age of twenty-one, the average student today will have spent more than 10,000 hours playing video games, will have sent or received over 200,000 e-mails and instant messages, will have talked for more than 10,000 hours on a cell phone, will have spent over 20,000 hours watching television, and will have spent, at most, 5,000 hours reading books.

Literacy, like the attachment of the human mind to the unfolding of reason that it represents upon the parchment scroll, has come full circle. The law of excluded middle propounded by Aristotle has evolved into the binary code of the computer, whose inner workings are based on the principle that anything that is can be described by means of an astronomically long list of things that it isn’t, a game of Twenty Questions so spectacularly boring that only a silicon brain can keep track of all the negations without falling asleep. Once the proposition that something cannot be A and not-A at the same time represented the height of reason, with literacy as a concomitant boon. Today, the exact same proposition—in its cybernetic embodiment—has become the great stumbling block in the way of literacy, and hence of its concomitant value, reason.

From the epistemology of the bon savage, rendered into the English of Romantic sentiment as “nature’s gentleman,” to the Hollywood antics of Crocodile Dundee, from the legend of Romulus and Remus to Kipling’s Mowgli, from quitting the real world in Where the Wild Things Are to refusing to enter it with Peter Pan—all these trends are evidence that Tarzan actually belongs to a vast family of the imagination: “I am as free as nature first made man, / Ere the base laws of servitude began, / When wild in woods the noble savage ran,” as John Dryden has it in one of his plays written in 1672. “Man left Eden when we got up off all fours, endowing most of his descendants with nostalgia as well as chronic backache,” wrote Gore Vidal in an essay on Burroughs. “In its naive way, the Tarzan legend returns us to that Eden where, free of clothes and the inhibitions of an oppressive society, a man can achieve in reverie his continuing need, which is, as William Faulkner put it in his high Confederate style, to prevail as well as to endure.”

The flight from reason did not begin with the men in suits on holiday in the Med. Attempts to redefine goodness, freedom, or happiness did not begin with Bill Gates and George Lucas. But never before in the history of civilization was the influence of these penny-whistle Pied Pipers so massive, their grip on contemporary culture so secure, their control over our minds so technologically and economically totalitarian. Literacy has no chance against odds like these.

Leave a Reply