In the opening pages of The Future of Christian Marriage, Mark Regnerus notes a troubling truth well known to anyone who has set foot in an institution of higher education in the last several decades. “To talk seriously about marriage today in the scholarly sphere is to speak a foreign language: you tempt annoyance, confusion, or both,” he writes.

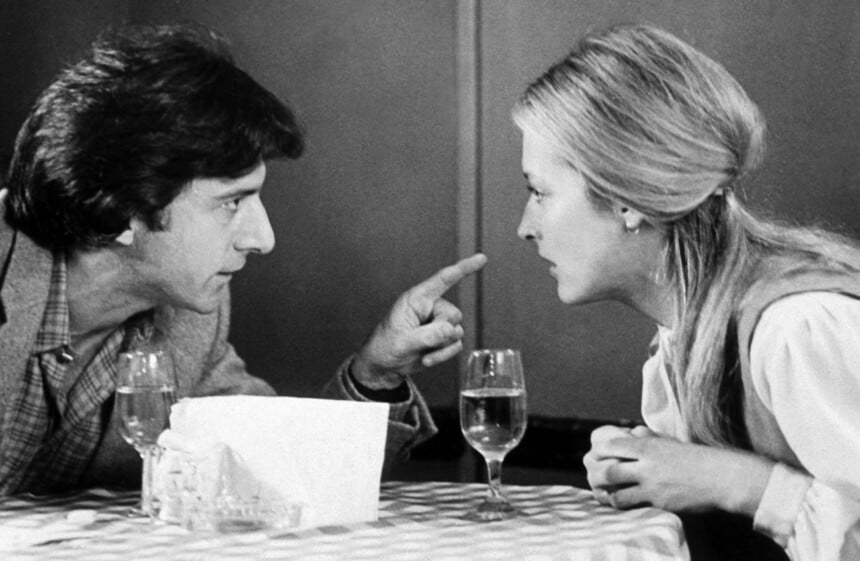

It is worth remembering just how recently this came to be. The revolution in marriage and divorce took place in the wake of the 1960s. Just a generation ago, one could easily find scholars who would defend, as a universal social good, the institution of marriage as a lifelong commitment of two people to one another and to their children. It was still possible in my youth in the late ’70s for an Academy Award-winning Hollywood film, Kramer vs. Kramer, to present the devastation of divorce, especially in its effects on children, basically unmasked.

Today, the cultural destruction of divorce goes mostly unremarked upon by our expert class. The divorce rate, which more than doubled between 1960 and 1980, has now dropped somewhat compared to the peak in the 1970s, but it is still about 70 percent higher than it was in 1960. And now, owing at least in part to the recognition of the fragility of an institution so undermined by the radical transformation of family law and culture, many more Americans than ever before avoid the very possibility of divorce by never marrying in the first place.

Any effort to reverse these trends first requires an honest, serious, and scientifically and philosophically rigorous discussion of the consequences of our current culture of marriage and divorce. Contemporary elite opinion tells us that marriage is a contract between pleasure-seeking, selfinterested individuals, in force only so long as both parties are fully satisfied with what they receive from the other, and breakable on the slightest pretense. Divorce is seen as of no import or consequence to the broader society, and it is claimed that it need hardly even affect the parties involved, as they are free to move along to other contracts as they like. Extreme individualism is the philosophical basis of this contract model, and it extends to the very nature of the institution of marriage. Elementary school children are taught that any claims that some familial and marital practices might be more effective at producing happiness than others are to be rejected in advance as nothing more than ignorant prejudice.

Facts must be sidelined in this effort at indoctrination. There is robust evidence that divorce often has serious negative effects on children. Children in intact biological families have better physical and psychological health, perform better in school, and are less likely to abuse alcohol than children in stepfamilies or single-parent homes. In the 1970s, many divorce-culture advocates argued that any undesirable impacts of divorce on children are short-lived. On the contrary, research that has followed children of divorce over the course of their lives has shown us that many of the damaging effects are long-term. Compared to their peers from intact families, for example, children of divorce marry less frequently, and when they marry, their unions are more fragile and more often end in divorce.

The adult parties to a marriage can also be harmed in significant ways by divorce. The divorced commit suicide at rates much higher than the married. The progressive and feminist criticism of marriage claimed that liberalization of divorce laws would inevitably empower women, who historically were less able to remove themselves from unhappy marriages than were men. But there is little evidence that women enjoy greater satisfaction with their experiences in conjugal relationships in the age of weakened marriage and easy divorce.

America has embraced a culture in which sex is ripped out of all moral contexts and made into a matter of an individual’s creative identity and pursuit of physical pleasures. This has had effects that the early proponents of this cultural shift did not predict. Among the chief of these is that the loosening of sexual taboos and restrictions made it possible for men to have sexual relationships with women without any of the burdens of courtship and responsibility that were required in the past.

Marriage, it is rightly said, civilizes men, and a good deal of male effort at status achievement expressed through productive work and morally responsible self-control is incentivized by making them marriageable partners for desirable women. If men can get sex without doing that difficult work, some can be counted on to forego the effort altogether. This trend contributes to making men less productive and less responsible. It also makes many less interested in marrying at all.

Both men and women are putting off marriage until later in life to pursue educational and career goals first. Coupled with the rising numbers of men who have fled marriage altogether due to easy access to a sex life without it, this puts many women who desire marriage into a difficult situation demographically. By the time they have established their careers and are ready to marry, they are in their 30s or 40s and nearing the end of their reproductive lives. From a shrinking field of candidates, they seek a mate who for biological reasons does not face the same reproductive window, who can wait longer and be pickier. The sheer demographic math suggests that many of these women will necessarily be unsuccessful in their search.

The traditional conservative view on marriage is in profound opposition to divorce culture. Children are the object of a marriage, in this view. Their potential existence already fundamentally informs the nature of the institution. Once they exist in reality, it becomes impossible to ignore the anti-individualist core of the intrinsically social unit of the family. Spouses have a clear obligation to the organic entity that is the family, which demolishes the contract model of relationships. Marriage creates not a contractual relationship between two independent persons, but a new society that has a reason for existence that goes well beyond the individual interests of its members.

This traditional conservative view of the family is based on the idea that successful human institutions and social arrangements emerge from basic facts about human nature and from experience over many generations, during which social practices are painstakingly honed according to their demonstrated successes and failures. Any institution that survives for long periods of time in a given form has thereby proven its effectiveness, and we would do well to think long and hard before modifying it significantly.

As it turns out, there is a confluence of evidence from the natural and the social sciences on the comparative advantages of permanent monogamous marriage. These facts buttress conservative philosophical and religious claims for the value of marriage so conceived.

For example, the favoritism shown by an individual to its biological relatives, known as kin selection, is universal in the animal kingdom, and human beings naturally engage in it as well. In what is known in the scientific community as “the Cinderella effect,” so-called “blended families” produced by divorce and remarriage show elevated rates of child abuse and neglect compared to biological families. Stepparents and stepchildren are frequently not closely emotionally bonded. Many stepparents desire a marital relationship with the adult partner but may be indifferent to that person’s children from another mate. They may even see those children as direct competitors for the time and attention of the other adult in the blended family. We are of course constantly admonished by divorce-culture proponents not to notice or talk about any of this, but the research on the topic strongly supports the existence of the Cinderella effect.

These facts suggest that families consisting of two parents and their shared biological children are comparatively advantageous for the children. But why monogamy, which is rare outside our species? In fact, polygyny, where one male may have several wives, is more common in human history. But the disadvantage of this kind of familial structure reveals itself in our highly social nature. We are tremendously skilled at organizing ourselves collectively to obtain desired social ends. A polygynous system inevitably favors high-status males, and it leaves fewer marital options for the much larger group of lower-status males. That is, to say the least, not a recipe for social harmony!

Cultural and legal monogamy eliminates the tension and potential strife of polygyny, and it is especially prominent in highly democratic societies where lower-status individuals have many ways to work collectively to get their interests realized against those of a powerful minority. High-status men suffer a comparative loss in the move to monogamy, in pure reproductive possibility at least, but the overall effect on the whole society is positive. In addition to the advantages for lower-status men, the emotional benefit for women who can monopolize the attention and resources of one husband rather than competing for them with other wives is considerable.

As insightful as they are, though, the requirements and pressures of biology and sociology do not tell the whole story of why lifelong monogamous marriage is best for us. The story of marriage, or of anything else, requires culture, as that is what provides the meaningful symbols and values that motivate us, beyond the forces of biology and sociology, to act in ways that affirm our morality and our humanity.

Culture sustains our moral life as a people. One of its most basic imperatives is to give us rules for ordering our familial relationships. Western culture was, like all cultures, deeply tied to religion at its origin, and the central Western religion, Christianity, was essential in shaping our institutions of marriage and family.

The professional despisers of traditional religion and culture endeavor mightily to ignore or deny the near-perfect fit of Christianity with the imperatives for organizing sexual partnerships and child-rearing given by human nature. But the case is easily demonstrated. Christian faith calls the believer in all his life’s endeavors to the imitation of a perfect model—“Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect”—as a method of moral improvement.

The basic familial institution, which should be based on an accurate assessment of human nature, has as its purpose the unity of the sexes and the bringing forth and nurturance of children in the setting most conducive to their moral growth. Marriage in its perfect Christian form, which endures for the whole lives of the couple, is thus the model. Our aim is the eternal, and if our efforts should lamentably fall short, we, and not the institution of marriage, bear the blame.

A perfect ideal is what best enables the taming of the powerful sexual passions that can otherwise easily produce anarchy. In the Christian perspective, sexual intercourse is a sacred undertaking, which means it must be regulated by ritual and proscription. It is no accident that the divorce culture that demolishes the eternal perfection in marriage also desacralizes sex, turning it into one more bodily pleasure among others to be engaged in however an individual wills. Alienation, conflict, and disease are among the most obvious consequences of a culture that profanes sex in this way.

above: The ratio of the number of divorced people to the number of married people in the United States, from 1867 to 2019. (Compiled by Chronicles staff using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the CDC National Center for Health Statistics.)

It is only at the cultural and religious levels that we can transcend the language of interests to that of selflessness and love. Love takes us beyond natural selection. Training in the virtue of true love is—in part because of its fit with the core of our nature—most effectively carried out in a family consisting of a permanently married couple and their biological children. Here there is the possibility of a profoundly shared life commitment, of being in a grand endeavor together, for the entire voyage, whatever may come, with the imperative to make it work whatever the difficulties and contingencies thrown at us by the chaos of life may be.

With the right cultivation, love can give birth to a spiritual perfection born from the unity of the complementary sexes, merged physically and emotionally to make new life that is a perfect blend of the one and the other. The soil of human nature feeds the flower of love, which in turn enriches and replenishes it, and simultaneously brings it to a state that transcends its mere materiality.

Catholic philosopher Thomas Molnar noted that utopians believe that we need only follow our own internal compasses to be perfect. Christians attend better to our true natures and the need for a project grounded in the real to approach that awesome goal.

The distinctiveness of Western marital culture has been recognized by Christian thinkers and purely secular scholars alike. Harvard human evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich, for example, has written several popular books exploring the origins of the unique successes of Western culture in technological, economic, and political spheres. He points to the Christian institutionalization of lifelong monogamous marriage as a crucial event in this advance. It was the Roman Catholic Church that produced the unique framework for family structure, which Henrich calls the “Marriage and Family Program,” which, among other features, prohibited polygamy and divorce.

Though it is certain that this framework for marriage helped birth and give advantage to the West, we may now be well into the process of squandering this unique achievement. Divorce culture is celebrated by our elites and sustained by the logic of American economic life. Employers have no interest in families and they act accordingly, demanding that we separate ourselves from our spouses and children at the whims of the job. They move us across the country and uproot us from the communities that might help stabilize our domestic institutions, all in the interest of their bottom lines. Many Americans long for traditional communities and the traditional families that made them up, but there is almost no chance to have either in our present culture.

One of the most startling things revealed—perhaps unintentionally— in the film Kramer vs. Kramer is the rickety value structure that forms the basis of divorce culture. The wife in the film, Joanna, is motivated by an egotistical desire to drop her maternal responsibilities and enter fully into the paid labor market. At the film’s outset, Ted, the family’s breadwinner, is also pathologically obsessed with his job to the detriment of his duties as a husband and father. The obsession with their careers is a leading factor in the destruction of the Kramer marriage. The professions of the two Kramers—fashion and advertising respectively— could not have been more effectively chosen to highlight the spiritual and moral insubstantiality of much remunerative work. How on earth do we come to see such things as anything more than a means to the much more important end of cultivating marriage and family life? How much must go wrong in a culture for the Kramers’ skewed priorities to become our societal norm?

In one telling scene, the film pronounces the single verity that the divorce culture most wants to reject. Ted asks Margaret, a divorced friend, if she thinks she will ever marry again. Margaret, a liberal feminist in her rhetoric up to this point in the story, shakes her head emphatically: “That stuff about ‘till death do you part,’ that’s really true.”

Image Credit:

above: Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep as Ted and Joanna Kramer in the 1979 film Kramer vs. Kramer (Columbia Pictures)

Leave a Reply