I was in seventh grade, and we were downstate for the annual Bible Bowl. Our little fundamentalist school fielded a team every year. We were the most conservative of fundamentalists, which mean that we were King James Only (affectionately KJVO). Along with soulwinning and no syncopation, KJVO was proof to the world that we were not dirty liberal Southern Baptists.

That year, our subject was the Gospel of Mark. Our team divided the book up, so that among us we had all 16 chapters memorized, right down to the snake-handling part in the end, which the New International Version (used by the dirty liberal evangelicals) set in italics, to indicate that it wasn’t the Word of God. Questions were fired at us over an ancient p.a. system, and we leapt to our feet to answer, causing a lamp to light and a buzzer to sound.

But our team wasn’t sounding many buzzers, falling into dead-last place by halftime. We broke for lunch, dejected. Mr. Kobernat, our faculty advisor, started cracking jokes, as was his custom, to lighten the mood. One wag among us looked up at him and said, plaintively, “Master, carest thou not that we perish?” Everybody laughed.

We weren’t Quakers, and that wasn’t our everyday talk. But Elizabethan English was a part of our everyday lives. Our preachers, relatively uneducated when compared with Mainline clergy or even with the Southern Baptists and evangelicals, could speak fluent Elizabethan. Every Wednesday night, at prayer service, they prayed in it. Father, we thank Thee that Thou hast deigned to bless us . . . They could read it at lightning speed, losing momentum only when approaching certain Hebrew names in the Old Testament. One Arkansas evangelist, who preached regularly at our summer camp, read the “old-feyshun King James Bah-bul” at such a pace that we wondered how he could breathe. His face was red, and he sweat, as it were, great drops of blood.

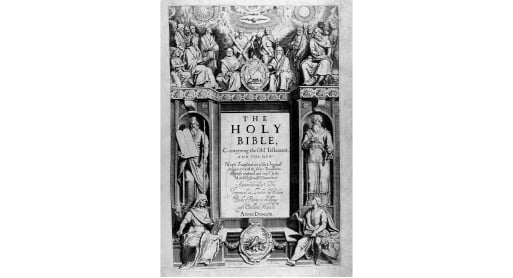

As we speak, that old-fashioned King James Bible is enjoying the 400th anniversary of its publication. And though it will be properly fêted by scholars and panelists in divers academic settings, there is no denying that, apart from its place of honor among my KJVO friends, it has finally started to yield up the ghost. And that is a shame, because the King James Version is, hardly arguably, the single-most influential book in the modern English-speaking world. So much so that, while its liturgical use is all but lost, it still sways the imaginations of those who once heard it.

As most of us well know, the liberal powers that be took the King James Bible out of America’s public schools in the 1960’s. For conservatives, that and the removal of teacher-led prayer were signs of the times. Yet how many today, liberal or conservative, would recognize the fact that those two phrases—the powers that be, signs of the times—come to English directly out of the King James Bible (Romans 13:1, Matthew 16:3)? The phrases feel familiar.

Matthew Norman, a columnist for the London Telegraph, writes not on religion but on “television, poker, and New Labour.” That is reflected in the title of his March 18 column, “Please Let the Blairs’ Coitus Be Interruptus.” (To drink freely from that well, see Derek Turner’s review in this issue.) But Norman followed that up on the 25th with “The Police Have Become a Law Unto Themselves.”

In “Caribbean Junkets, Zeppelin Heads, Goldman Sachs and Mr. Magoo,” Bill Singer of Forbes.com wrote (April 19), “Which of those interrogating Senators didn’t accept campaign contributions or lobbying funding from Wall Street? Which of those paragons of virtue returned all the filthy lucre from these now contemptible lowlifes?”

Featured on March 30 on the ABC News website, former Liberal Party (Australia) press secretary David Barnett opined of New South Wales Premier Barry O’Farrell, “His transformation from the bland all-things-to-all-men cloak-of-many-colours he has worn for the past four years to the determined, even stern, leader who took the podium on Saturday evening is quite striking.”

One John Smith, a Las Vegas journalist who writes for the Mesquite Local News, summarized the position of opponents of recent antidrug legislation as follows: Because “changing the law would do little in the long run to stop the flow of the drug in the state—much of Nevada’s meth is imported from Mexico—the end result is that nothing more is being done on the front lines to fight the good fight against the proliferation of a devastating illegal drug.”

Phrases like “fight the good fight” (1 Timothy 6:12), “all things to all men” (1 Corinthians 9:22), “filthy lucre” (1 Timothy 3:3), and “a law unto themselves” (Romans 2:14) roll off the tongue, not as churchy talk but as cultivated English. We know what it means to be brokenhearted and kindhearted. We warn people to judge not. We may even have watched Robert Duvall learn of Tender Mercies (1983). These and countless other examples demonstrate the power of a sacred text to shape language; and as any poet knows, language shapes thought.

How this particular shaping came to be involves an interesting collision of theologies, politics, scholarship, ignorance, creativity, and—above all else—conservatism.

To begin, the King James Bible was not really meant to be a translation but a revision of the backward-looking Bishops’ Bible (1568). The two warring factions who produced the King James were the Anglicans and the Puritans. Both sides, as Protestants, agreed that Christians must be provided a translation of the Scriptures in the vulgar tongue. They also concurred that the norma normans of the text should be Hebrew and Greek, not Latin. But the Anglican side had their Bishops’ Bible, and the Puritans preferred the widely popular—among Puritans and lay Anglicans alike—Geneva Bible (1560).

Geneva was a brilliant achievement, a product of the friendship struck between English Protestants and Calvin’s Geneva during the sanguine reign of Mary Tudor. It represented the first translation of the full Old Testament from Hebrew into English. (Coverdale, not knowing Hebrew, had worked from the Vulgate.) The Hebrew sings rhythmically in Geneva’s English, with marvelous parallelisms and assonance. Here we first hear such gems as “Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth” (Ecclesiastes 12:1).

The Anglican hierarchy recognized the brilliance and the power of the Geneva Bible, but they were bothered by what they (and the Catholics who produced Douay-Rheims) found to be an excess of Calvinism. For starters, Geneva translates the Greek episkopos as overseer and presbuteros as elder, a matter of slight concern to bishops and priests. But the real mischief, they believed, was in Geneva’s marginal notes. There they seem to have found the whole of Calvin’s Institutes, including the offensive word Mesopotamia.

And so they produced the Bishops’ Bible, which was a philological disaster. Lacking the Greek and Hebrew scholarship of their Calvinist enemies, they butchered the text. “He maketh me to rest in green pasture” (Geneva) became “He will cause me to repose myself in pasture full of grass.” Having purged themselves of the balm of Calvin, they asked, “Is there not treacle at Gilead?”

It should come as no surprise, then, that when Old Six and One arrived in England, he was beset by angry Puritans who did not want the “Treacle Bible” (as it came to be called) imposed upon their pulpits. And so, at the Hampton Court Conference in 1603, King James decreed that a new version—one that would unify and edify all of England—should be produced. To that end he appointed committees comprising both Anglicans and Puritans. The catch, which showed favoritism to the former, was that this was not supposed to be a new translation per se, but a revision that would “make a good one better.” The good one was the Treacle Bible. And the proviso was that the “better one” should be free of “bitter [marginal] notes.”

And so they set about their task, finishing in 1611. But what they produced was not a Supertreacle, but a conservative return to the best of Geneva and Geneva’s literary grandfather, William Tyndale.

Tyndale was a linguistic genius who devoted his life to the sacred text. He was an early English Lutheran during the days in which Henry VIII defended the faith with the help of Thomas More. Tyndale had embraced Luther’s idea that the Scriptures are as much for the plowboy as they are for the pastor. Thomas More recognized Tyndale’s gift and thus devoted literally thousands of pages of vituperation to securing his demise. (More’s Tyndale roamed the countryside “discharging a filthy foam of blasphemies out of his brutish beastly mouth,” serving Luther, who was “most fit to lick with his anterior the very posterior of a pissing she-mule.”) Indeed, it was Tyndale, working from Greek instead of Latin, who first changed bishop to overseer, priest to elder or senior, church to congregation, and charity to love. Thomas More noticed this more than once.

Tyndale’s monumental work was to make the first translation of the New Testament from Greek to English (as well as the Pentateuch from Hebrew). And it was, as scholar David Daniell’s work shows, an exquisitely Anglo-Saxon English. Unlike often multisyllabic Latinate English words, Anglo-Saxon English is quick and sharp. As one of many examples, Daniell points out that, in the following passage from Tyndale’s Matthew 26, only disciples is Latinist English: “Then went Jesus with them unto a place which is called Gethsemane, and said unto the disciples, sit ye here, while I go and pray yonder.” Even an old-fashioned preacher can read that quickly.

The austere John Wycliffe, some 200 years before, had translated from Latin. Interestingly, Douay-Rheims and Wycliffe agree, word for word, on Genesis 1: “And God said, be light made. And light was made.” Tyndale, from the Hebrew, first gives us “Let there be light.”

All English Bibles after Tyndale (including Douay-Rheims) have borrowed from him, to greater or lesser extent, sometimes improving, sometimes—as with the Bishops’ Bible—not. Computers can now tell us that 83 percent of the King James Bible is Tyndale. Of course, the Anglican and Puritan scholars compared everything with the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, and even consulted the Vulgate. But Tyndale was ringing in their ears. Indeed, all of my previously cited common English phrases from King James were Tyndale’s. He coined the powers that be.

In that sense, the KJV was conservative. It ditched the Treacle in favor of the language that had already united and penetrated the minds of Englishmen, including Shakespeare. (Notice the Tyndalian syllables of “O for a muse of fire, that would ascend the brightest heaven of invention,” in which only ascend and invention are distinctly Latinate.) True, King James employs a neologism popularized by Shakespeare (amazement—Tyndale has “they were sore astonished”). But the bulk of it was deliberately archaic. For example, in 1611 the pronoun ye was no longer the common second-person nominative. (Shakespeare freely uses you.) But so memorable were the likes of Tyndale’s “Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you”—borrowed by Geneva, the Bishops’ Bible, and Douay-Rheims—that ye remained in King James in its older usage. This deliberate archaism flouts the common objection hurled at the KJV today: No one talks that way anymore. No one talked that way in 1611, either.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m no KJVO. Those folks have various and sundry reasons why they demand that version, including a strong preference for the Greek text (the so-called Textus Receptus) that served as its base. Setting aside an abstract evaluation of that abstract argument, I only note that Tyndale was the true texts receptus underneath the King James. The chief problem with modern critical Greek texts is their abuse in the hands of liberals with an agenda, as was the case with the Revised Standard Version (1952) and its bias against the virgin birth of Christ.

What makes me sympathize with my KJVO friends is their instinctive notion of—of all things—catholicity. The shared text of King James was indeed a unifier (bishop and charity won in 1611), both of warring factions and of generations. The sacred text that my dear granny memorized and quoted freely is the sacred text that still permeates my imagination. Biblically, I still think in Elizabethan.

Today, catholicity has given way to individualism and instant gratification. New translations are churned out (it seems) annually. It’s far more difficult for language to shape thought (“Let every thought be captive . . . ”) when it is constantly changing. To today’s LOL Generation, “Don’t let the excitement of youth cause you to forget your Creator” (New Living Translation) is more immediately accessible than “Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth.” But is it as penetrating—or memorable?

Leave a Reply