Imagine reading an interview with the founder of a new Christian church. As the interviewer points out, new denominations are scarcely a surprising story, so what makes yours so different and noteworthy? Well, explains the prophet, we have a totally different attitude toward the Bible. Our focus groups tell us that many modern people do not like or do not understand large portions of the Bible, about half of the book in fact, and we want to serve their needs. The God we preach is, above all, Nice, and the scriptures must focus on that paramount reality. So our church has produced a new version of the Bible, carefully selected for Niceness, and edited to remove the half of the material that modern readers find difficult, unpleasant, or thorny. That is our belief—or, as we call it, our Nice Creed.

In reality, such a statement could hardly exist outside the realm of satire. But the basic idea—the mass purging of difficult material from the Bible—is exactly what has happened in recent decades, and not only among my imaginary Niceists. Not just in the United States but across the English-speaking world, the great majority of Christian believers, Catholic as well as Protestant, select their service-time Bible readings from the Revised Common Lectionary, which first emerged in 1969 as the Lectionary for Mass, was published as the Common Lectionary in 1983, and reached its final revised form in 1994. In practice, the lectionary treats the biblical text exactly like the Niceists. The lectionary offers an anodyne canon-within-the-canon, which includes less than half the whole biblical text.

The idea that the Bible has difficult and unacceptable passages is anything but new. In the early Christian era, such a theory inspired a whole alternative version of the faith, which found its prophet in Marcion of Pontus. Even his deadliest foes admit his prominence in the Christian community. Marcion, though, could not accept the conventional Christian approach to the unity of the biblical text. As he studied the Old Testament, he was appalled by the picture of God that emerged. In Marcion’s view, not only did this “author of evils” command the ruthless slaughter of enemy peoples, but he savagely punished any of his own followers who showed qualms about the bloodshed.

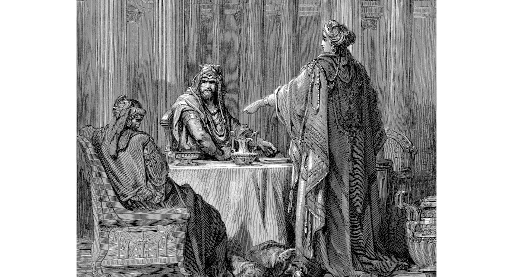

Exhibit A for Marcion, and for many of his followers, was the story of Saul and the Amalekites, a people against whom God had declared eternal enmity. According to the First Book of Samuel, God ordered King Saul to strike at the Amalekite people, killing every man, woman, child, and animal. When Saul failed to annihilate the enemy, he earned a scolding from the prophet Samuel, who himself slaughtered and dismembered the Amalekite king Agag. Saul’s sin was failing to be sufficiently total in acts of massacre, and his disobedience led to his own destruction and the fall of his dynasty. The Book of Joshua, meanwhile, reports the divinely ordained conquest of the land of Canaan and God’s command to perpetrate genocide against the inhabitants of many cities and regions. Even more alarming for Marcion, many such passages show God “hardening the hearts” of Israel’s enemies, to reject compromises that might have averted their destruction.

Obviously, such passages lend themselves to many interpretations, and faithful Bible believers—Jews and Christians—throughout history have found ways of understanding these texts, of fitting them into their vision of a just deity. Perhaps the stories are allegorical; or perhaps they are historical and are intended to teach weighty truths about God’s absolute sovereignty and human sinfulness. For Marcion, though, no such solutions were possible. So numerous were the Bible’s dark passages, and so egregious, that they must record the acts of an evil god, a dark father quite distinct from the good god of Light revealed by Jesus. The Old Testament described the god of the evil material world and (concluded Marcion) the god of the Jews. Marcion accordingly devised an alternative bible, wholly free of the Old Testament, and consisting mainly of suitably bowdlerized selections of St. Luke’s Gospel, together with edited versions of the epistles of Paul.

You would be hard pressed today to find a self-described Marcionite, still less a functioning Marcionite congregation, but Marcion’s ghost still walks, and exorcising that nagging spirit is an essential task for each new Christian generation. While Marcion had wanted to remove the whole Old Testament from Christian usage, virtually all modern Christians acknowledge their indebtedness to the Hebrew Bible. But accepting the Old Testament does not suggest equal enthusiasm for every passage in that large collection, and over the past few decades many churches have in practice suppressed large portions of that work.

Christians have always read Bible passages as an integral part of their services, and for this purpose they have produced lectionaries, collections of texts appropriate for Sundays and for given days in the Church year, with the different elements chosen on the basis of some common theme or relationship, and usually some relationship to the day or season. Commonly, these texts provide the basis for the day’s homily or sermon. Before the 1969 revision of the lectionary, readings from the Old Testament were largely confined to the daily lectionary; Sunday and holy-day readings included a psalm, an epistle, and a gospel lesson; and the lectionary followed a one-year cycle. In order to give congregations the widest exposure to scripture, the Revised Common Lectionary and its antecedents spread readings over a cycle of three years and included an Old Testament reading for each Sunday and holy day.

Over a three-year span, believers easily work their way through most of the New Testament text, but the Old is much lengthier and must be edited carefully. Unfortunately, that process of editing and selection demonstrates a powerful agenda that can best be described as Marcionite, a desire to purge exactly those Old Testament elements that most repelled that ancient heretic. What remains in the text is an acceptable Bible Lite.

Assume that a person regularly attended a church that used the Revised Common Lectionary; in fact, that he never missed a single Sunday or holy day. If he listened attentively to the readings over the three-year cycle, he would hear just a small and unrepresentative selection of the controversial Old Testament passages. Some whole books have virtually disappeared.

Look, for instance, at the Book of Esther, a romantic story that tells of conspiracies at the Persian royal court. The king’s evil counselor Haman plots to kill all the Jews of the empire, but is prevented by the wise Jewish courtier Mordecai, together with the glamorous queen Esther. But Esther is also a book of blood, one of the most brutal tracts in the Bible. After Haman is hanged, the Jews inflict on his people all the slaughter he had intended against them. Many Persians convert to Judaism because of “the fear of the Jews” who “slew of their foes seventy and five thousand.” Although God did not command the act, the massacre is commended, and commemorated in the feast of Purim. The Book of Esther was duly canonized in the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian Bible.

How would modern Christians hear all this? Actually, most wouldn’t, at least in churches that used the Revised Common Lectionary. Over three years, a church member would hear just one brief extract from Esther, around six percent of the whole text. While the reading reports the hanging of Haman, it has nothing about the subsequent pogroms. The selection culminates with the establishment of the sacred feast, marked by joy and gift giving, but with no hint about the reason for the merriment. In terms of the ordinary experience of Christian Church life, the Book of Esther has ceased to exist. So has the Book of Ezra (not quoted at all in the lectionary); so have Judges, Leviticus, and Nehemiah (each represented by one meager passage). All these books have succumbed to an effective textual cleansing.

Even when books remain in the lectionary, they are subject to an editing process that pays little heed to context. Often, the compilers carefully select texts to serve their purposes, omitting hard sayings, although only the astute reader will note the elision. A passage will be cited as (for instance) “Leviticus 19:1-2, 9-18,” without any explanation of what has vanished from that chapter. Just what was in verses three through eight?

Throughout the lectionary, editors have made draconian decisions about eliminating material that is not suitable, relevant, or, well, Nice. They are for instance quite prepared to include the passage from Numbers about the bronze serpent that Moses raised for people to gaze upon and be healed. Christians have long seen that story as a foretaste of the Crucifixion, and it is used in this sense in John’s Gospel. Otherwise, Numbers has all but vanished. The lectionary fails to include other potent sections of that book, including the ruthless destruction of the enemy kings whose hearts were duly hardened, and the chilling story of Moses’s massacre of the Midianites. Preachers thus have no need to explain to their flocks why Moses ordered his warriors to wipe out the Midianite people, but to leave alive those girls who remained untainted by sex.

The lectionary draws heavily on the two books of Samuel, not surprisingly because David is believed to prefigure Christ. Yet the struggle of Saul and the Amalekites is absent, as is the killing of Agag. This reads oddly because the lectionary does include the story that immediately follows that incident, when Samuel deserts Saul to find a new king and anoints David. Without the Amalekite incident, though, that story has no context or explanation.

Joshua, too, has been so thoroughly censored as to lose most of its meaning. Only a few short passages remain, one about an apparent prefiguring of the Eucharist, one about the Israelites crossing the river Jordan. Listening to these texts, Christians are meant to see the Israelites entering Canaan as a foretaste of the Church being redeemed from sin and death, crossing over the river into salvation. So what is left out here? While all the passages that are included concern the conquest, conspicuously missing from them is the annihilation of the peoples of Canaan. The lectionary includes not a word from the heavily mined texts in chapters 6 through 11, the hard-core texts of wholesale massacre and heart-hardening. Although the lectionary quotes the introduction of Joshua’s final chapter, it then skips ten verses, without warning listeners of the transition. In fact, these omitted verses recount the conquest and destruction of the Amorite and Moabite peoples, the annihilation of Jericho, and the ethnic cleansing of the seven peoples of Canaan. Leaving out that section, we imagine the rival peoples listed in this chapter as armed enemies in battle, not as civilian targets for genocide.

Why should we worry about this radical purging of the biblical text? After all, Christians are not forbidden to read the troubling texts on their own, either in a private context or in a common study group. Yet having said this, many such groups like to use the lectionary as a guide for such activity, either using the texts for the coming Sunday, or else linking the study to a sermon. Ordinary readers are free to explore Joshua, Ezra, and Deuteronomy, but how many do? If you are a faithful church attendee—a Catholic or Presbyterian, Methodist or Episcopalian, Lutheran or Mennonite—the odds are that you simply will not encounter some of the Bible’s most challenging passages, texts that must be understood if we are to see that work holistically. Jesus, after all, was really Yeshua, and He shared His name with the ancient warlord we call Joshua, the book of whose deeds has virtually disappeared from Church usage.

The worst feature of this far-reaching excision of troubling texts is what it suggests about the churches’ attitude toward their ordinary believers, who must be protected from anything that might call them to question the orthodoxies of the day. God forbid that they might actually hear these texts: They might be induced to think.

Leave a Reply