A theory about the mafia that was advanced in these pages by the late Samuel Francis about 15 years ago explains how Walmart, Costco, and Home Depot drive out your corner grocery, the local pharmacist, and Joe’s Hardware. The national expansion of these blights isn’t free enterprise. It’s more akin to the nationwide expansion of organized crime a century ago.

Francis pointed out how organized crime originally was concentrated in local areas, where the mafias, camorras, and triads could bribe local politicians and police. Each mafia exploited its own territory and had difficulty expanding to a distant, unfamiliar area. The mafia’s main criminal enterprises—prostitution, strong-arming, and gambling—were not commodities that could cross state lines, with the exception of the occasional major boxing match or the 1919 “Black Sox” World Series.

Alcohol was prohibited only in states in the South and Midwest, where Methodists, Baptists, and other teetotaling denominations predominated. Prohibition did not exist in the major cities of the Northeast because the dominant religions were Catholicism, Lutheranism, Episcopalianism, and other bibbing denominations, as well as Judaism. So alcohol smuggling meant rural good ol’ boys in the South tending to a still in the woods and bootlegging it to customers in cars custom-built to evade the “revenuers.”

That changed with national Prohibition, first enacted as a wartime measure in World War I and made permanent with the 18th Amendment. The Noble Experiment went into effect in 1920 and prohibited the

manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes. . . . The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

It was the last time the U.S. government went to the bother of actually amending the Constitution before vastly increasing its powers over our lives.

As Francis argued, the key expansion of federal authority was in granting Congress the “concurrent power to enforce” Prohibition. The means of executing this power were outlined by the Volstead Act. Almost a century later, it’s amusing to read how the act’s full title granted the federal government the power “to ensure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye, and other lawful industries.” Sacramental usage also was exempt.

Francis’s original insight was that this nationalization of Prohibition led to a nationalization of organized crime. Instead of bribing only local politicians and police, the gangs would have to bribe congressmen, senators, and federal police. The gangs quickly began to import distilled spirits, especially from Canada. During the harshest weeks of winter, the Detroit River freezes over, allowing even heavy trucks to sneak over from Windsor, Ontario, to Michigan. The river is 28 miles long and as narrow at points as half a mile across.

The hooch found its way to the numerous speakeasies in Detroit, Chicago, and other cities ruled over by such colorful murderers as Al Capone and the Purple Gang. Despite the pleading of preachers, most adults still drank. Prohibition was advanced by both major parties and most officeholders. As H.L. Mencken quipped at the time, voters “staggered to the polls to vote dry.” President Harding, in office 1921-23, took breaks from his adulteries to play poker and drink whiskey in the White House with his cronies.

Prohibition ended with the passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933, returning alcohol regulation to the states. But the expansion of organized crime across the country continues to this day.

The Volstead Act, although negated by the 21st Amendment, had given the federal government a taste of nationwide regulation. Soon, it was drunk with regulatory power. To fight the Great Depression, President Hoover anticipated FDR’s New Deal with his creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Home Loan Board, and the Public Works Administration. In 1933, FDR’s entitlement program further increased government involvement in the economy.

FDR also “packed” the U.S. Supreme Court with cronies favorable to his expansion of federal power. Expanding the Commerce Clause to ridiculous proportions, in Wickard v. Filburn (1942) the Court unanimously ruled that the federal government could regulate Ohio sodbuster Roscoe Filburn’s personal use of his own homegrown wheat.

Following the Francis Theory, these federal actions—and thousands more—effectively created a national economy best exploited by national corporations with a heavy lobbying presence in Washington, D.C. As with the organized-crime bosses, the locus of action no longer was the state legislature or city council, but Congress and federal regulators.

One obstacle remained for the rise of the empires of Walmart, Costco, and Home Depot: local likes and dislikes. Joe’s Hardware had an advantage: Joe knew what his local customers wanted, which was significantly different from what customers wanted a hundred miles away, let alone a thousand. Joe, typically, grew up in the business and inherited his store from Joe Sr.

That advantage ended around 1987, when Walmart launched what was then the world’s largest private satellite network, allowing the retailer instantly to collect daily sales data from every single branch, use computer algorithms to predict demand, then send out inventory from central locations, such as Walmart GHQ in Bentonville, Arkansas. This inventory revolution meant little shelf space was wasted on items no longer in demand, and prices could be adjusted precisely to maximize sales and profits.

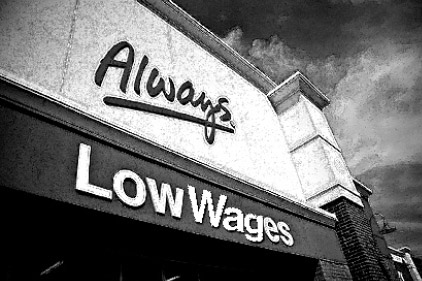

Joe never had a chance. Mrs. Grady continued shopping there because Joe always kept the Angel Wings perennial rose seeds in stock, which only she bought once a year. How quaint. Most other people preferred Walmart’s “Always Low Prices.”

I saw Walmart’s political operations firsthand in 1999 in Huntington Beach, where I have lived for 25 years. As with most school districts in California’s coastal areas, beginning in the mid-1980’s Ocean View School District saw enrollment decline, despite the strong increases in the state’s population of 26 percent in the 1980’s, 14 percent in the 1990’s, and 10 percent in the 2000’s. Population growth, mainly immigration from foreign countries, mostly occurred inland. To this day, “Anglos” still dominate along the coast. But Anglos suffered declining birthrates, while government regulations drove up the price of homes along the coast to levels prohibitive for young families. Although still outnumbered by whites overall, Latino students became a majority in the school district. Yet the overall numbers of students still declined.

In 1992, the district decided to close Crest View School, a kindergarten-through-eighth-grade school. Students were shifted to a school a mile away.

Enter Walmart. It proposed tearing down Crest View and erecting one of its stores. But Walmart didn’t want to buy the property outright. It wanted a 65-year lease. Walmart, with the savvy that made it the world’s biggest retailer, preferred not to speculate in California’s volatile real-estate market.

Walmart dangled before the district $41 million in payments over the lease’s duration. And the city council was promised $400,000 per year in sales-tax revenues. At the time, the city needed the money to goose the pay and pensions of its police force. Incidentally, the Huntington Beach Police Officers Association is the city’s most powerful political group.

Opponents pointed out that nobody could predict what would be the best use of the property for 65 years, and that Walmart would destroy a lot of local businesses that had built the city by paying property and sales taxes for decades.

At the Orange County Register, I wrote numerous editorials urging the school district to auction the property to the highest bidder, returning the estimated seven million dollars in proceeds to the taxpayers who paid for the property decades earlier. Or they could have used the money to make repairs to existing schools.

The city council voted in favor of the Walmart. It later turned out that George Argyros, a prominent Orange County developer who was involved in the Walmart development, was a major investor in Pacific Liberty Bank. Huntington Beach Mayor Dave Garofalo was on the bank’s board of directors. Reported the O.C. Weekly, “Their relationship at Pacific Liberty predates the City Council’s final vote to approve the Wal-Mart—a fact not disclosed during the actual vote.”

State and local authorities cleared Garofalo of any conflict of interest in the Walmart matter. But in 2002 he pleaded “guilty to a felony and 15 misdemeanors for voting on matters benefiting companies that bought advertising from his publishing business,” reported the Los Angeles Times. Typically for modern conglomerate-dominated America, Hizzoner was nabbed for being in bed with small-time local businesses, while the Big Boys got away.

In 2000, local activists put on the Huntington Beach ballot Measure I, which would have repealed the sweetheart deal between Walmart and the city and the school district. The activists pointed out, among other things, that the school district had offers of twice what Walmart was offering. I wrote Register editorials supporting the passage of Measure I, and again urged auctioning the property to the highest bidder.

This was where Walmart’s conglomerate genius came into play. Until then, they had mainly worked behind the scenes. But now they had to deal with actual voters. Bentonville air-dropped a platoon of p.r. flacks who contacted the local media, including me. In the weeks leading up to the election, they were my best friends. “Call any time, day or night,” they enthused. They gave me their cellphone numbers—something rare in 2000, before cells destroyed our lives.

It didn’t matter that my Register editorials opposed Measure I. “No problem,” they said. “We just want the voters to be informed.” They mailed, e-mailed, and faxed me numerous fact sheets. I’ve seen thousands of political, foundation, and business p.r. campaigns over the years. But this was the best. It was even better than the NAFTA snow job back in 1994.

Measure I lost by a 54-46 percent margin. According to a Register news story, Walmart pumped $380,000 into the campaign, or $14 per vote. To get a reaction from Walmart, I called my “best friends” in the p.r. department. I called their cells, their hotel rooms, and their offices back in Arkansas. Nothing. They had decamped the evening of the election, not caring about the outcome. It wasn’t their city. It was a plot point on a spreadsheet.

The store was built. In the end, Walmart won big. The year of the lease, 1999, was the first year of the real-estate boom that would engulf the area. From 1999 to 2006, property prices in the area quadrupled. Even in the aftermath of the 2007-09 real-estate bust, property values still are triple their 1999 values. The location is just 4.5 miles down Beach Boulevard to the Pacific Ocean and its golden sands. This is not Riverside County, where property values dropped 80 percent and never recovered.

The local mom-and-pop stores, the local environmental activists, the families with houses next to a noisy new store with thousands of cars pulling into its parking lot every day—none of them had tens of thousands of dollars to pay for top-notch lawyers, lobbyists, campaign consultants, or even, in 2000, cellphones. They never had a chance. They were bulldozed, figuratively and literally.

Walmart’s armies included not only the p.r. flacks but national lawyers and their California and Orange County affiliates, regulatory experts from all levels of government. State laws have mimicked federal laws in their regulatory profusion. In California, a gigantic and preposterously convoluted state, any project such as a Walmart must submit an Environmental Impact Report under the aegis of the California Environmental Quality Act. For a mom-and-pop outfit, it can take years before the first shovel hits the dirt. The new Walmart in Huntington Beach opened its doors just shy of two years after the defeat of Measure I. It didn’t hurt that Walmart CEO and President Lee Scott, in a letter to new Mayor Debbie Cook, promised to shower 40 local “community organizations” with $66,300 in largesse “when our store opens.”

So, here’s how it works. The federal government borrows trillions from China, the interest paid for with your high taxes. China sends us cheap junk to stock Walmart shelves. Walmart uses its national scope and hordes of lawyers and bureaucrats to bury local businesses and buy local politicians. Local stores, which once sold durable goods with a smile and supported local Little League teams, are driven from business. Social Security and Medicare go broke, and you end your days a greeter at Walmart.

Practically every area of our lives is dominated by these national and international business combines that are hooked into the federal government as if to a Siamese twin. They have the same circulatory system and spinal cord.

Another example is Big Agriculture, which dominates almost our entire food supply. In May 2011, I attended the sixth-grade graduation ceremony of the child of friends of mine at a public elementary school in Newport Beach. While it was proceeding, the younger kids were going through their routine school day, including lunch. This is one of the wealthiest areas of America, with median home prices well over one million dollars. Yet the kids were served pre-made pasty mush that would have made Oliver Twist wretch. The mush was made by major American food conglomerates and given the USDA stamp of approval.

Three months later, in August 2011, federal, state, and local authorities raided the Rawesome Foods cooperative in Venice, California, for selling unpasteurized milk. Three people were arrested: James Cecil Stewart, Sharon Ann Palmer, and Eugenie Bloch. Stewart maintained that the arrests were unwarranted because Rawesome was not a retailer, but a “private club whose members paid an annual fee and service charges to obtain products directly from farmers,” reported the Los Angeles Times.

I’ve purchased raw milk and cheese from other sources, and found it to be far superior to the pasteurized kind. I understand the risks. I also understand that, following the Francis Theory, small outfits like Rawesome face awesome challenges in the face of a powerful government. Meanwhile, the major national food conglomerates can make billions stuffing poisonous slop down the gullets of even rich people’s children.

Yet another target is vitamins. The Big Pharma drug companies don’t like it that you can treat yourself outside their prescription-profit closed system. I’m not a doctor, so don’t take this for medical advice. But I know that these remedies sometimes work. Eight years ago, thanks to a natural-supplement book, I discovered that digestive enzymes would actually end my acid reflux, whereas expensive Prevacid only relieved the symptoms; and an oil called cetyl myristoleate worked better than Celebrex to relieve arthritis, without the possible heart-attack inducing side effect of Celebrex.

Now the FDA, which is effectively controlled by Big Pharma, wants to regulate, even ban, vitamins and other supplements. The FDA’s New Dietary Ingredient protocols mean that, “once certain supplements are banned, Big Pharma would likely begin developing and eventually patenting the formulas for those items,” Deirdre Imus wrote in December 2011 for FOX News. She’s president and founder of the Deirdre Imus Environmental Health Center at Hackensack University Medical Center (as well as the wife of radio host Don Imus).

Imus added that Big Pharma companies, “unlike independent manufacturers, are more than capable of footing the hefty bill associated with the regulatory testing process.” Which means that “soon enough the companies bringing you conventional medications would be the same ones offering alternative treatments. Consumers’ money would be going into one big pocket.”

Soon, we may have to get our vitamins from bootleggers.

Leave a Reply