What has brought upon us the madness of the “transgender,” with all its sad denial of the beauty and particularity of male and female?

To see the cause, we must diagnose the malady. It is boredom: an irritable impatience with the things that are. Having lost a strong sense of creation and of nature as a gift from the Creator, we reduce the natural world to a fetish-object, or to inert and meaningless stuff to be manipulated for our pleasure. That stuff includes our own bodies.

It was inevitable that it should be so.

When that admirable old materialist Lucretius looked upon the world as it presented itself to him in the first century B.C., he saw beauty and order, the “leaf-springing homes of the birds and the greening fields,” the splashing of rills over the slippery rocks, meadows stippled with flowers, and “places of sunlit solitude and peace.” But when it came to accepting that same world with gratitude, the poet of ancient Rome balked. It could not have been made by the gods. It could not have been made for man. “There’s too much wrong with it!” he exclaimed.

So we should not be surprised by the disdain, even weariness, that arises out of Lucretius’s world like a fog, despite his better nature. If an old man should hesitate about dying, Nature has no consolation for him. “Get your sobs out of here, scoundrel, and quit your whining!” she cries. For she has nothing new for him to experience. It will be all “more of the same,” should he live to be a hundred. Same old, same old; and indeed the very same collocations of atoms in empty space will eventually occur again, given the infinite expanses of time. It is the theory of recurrence that fascinated Nietzsche and filled him with metaphysical loathing. Lucretius never finished his long poem outlining Epicurean philosophy, De rerum natura (“On the Nature of Things”), but I still think it fair to notice the conclusion of what we do have. The epic that begins with spring and new life ends with a pathetic and hopeless account of the great plague at Athens, when men were reduced to shedding blood in order to bury their dead.

Lucretius’s writing strikes us as modern, but he is no scientist. Witness his lack of interest in how large the sun is: about as big as it appears to our eyes, he says. It doesn’t matter which explanation of thunder you accept, so long as gods are not in it. Virgil is the greater poet, requiring us to enter a moral and religious universe that is different from our own and quite difficult to understand. Lucretius makes no such demands on us; indeed, he wishes to relieve us of the responsibility of moral understanding. As modernists do, he reduces. To Lucretius, all things are no more than the random collisions of atoms in empty space. Perception is merely passive: We are struck by films of atoms as inevitably and as unwittingly as the sunlight strikes a pane of glass. To him, the primary sense is not sight, with innate understanding of immateriality, and its opening forth into metaphysics. It is touch, the most brutishly material of the five.

You may think that someone who glorifies the sense of touch would exalt sexual pleasure to the height of human bliss. But Lucretius does not, nor did his master Epicurus. They were too honest for that. When your ideal is ataraxia, or freedom from trouble, you should flee from sexual desires, and be sharp in finding fault with physical beauty:

For men are blinded by their appetites

And grant their loved ones graces they don’t have.

The vile, the crooked—these, we see, are sweethearts

And are honored in the highest by their lovers.

As with the natural world, so with women. In this regard, Lucretius is like Cato, who sniffed with contempt when he saw a young man passionately in love—that is what whores are for, said he. So Lucretius: “Stroll after a street-strolling trollop and cure yourself.” That does not mean that he is opposed to marriage. The race must be perpetuated. And Lucretius did have a soft spot in his heart for children. He counseled a middle road in marriage: Choose a wife of merely acceptable looks, who is not a shrew. Passionate love is unnecessary, for you and she will get used to one another:

For habit is the recipe for love.

A thing struck over and over, no matter how lightly,

Will give in at long last and totter and fall.

Notice how water dripping upon a stone

Bores a hole through that stone eventually?

That is not meant ironically. It is the culmination of Lucretius’s discussion of the matter:

“Do you love me?” asks the girl.

“Hardly,” says the boy. “But I think I can get along after a while.”

Compare this attitude with one expressed just a century later. “Husbands, love your wives,” says Saint Paul, “even as Christ also loved the church, and gave himself for it; that he might sanctify and cleanse it with the washing of water by the word” (Ephesians 5:25-26). Those words come from a different moral universe altogether, a universe rich in meaning, one in which the human body is not, as all things in the Epicurean universe are held to be, the result of a random collision of atoms in empty space, but the bearer of real significance, both in the instant and across the range of human history. The Christian view of the body is meant to be the very temple of the Holy Spirit. No bridge can be thrown from one of these universes to the other. There is no middle term between meaning and unmeaning, between the existent and the nonexistent.

I am not here concerned to show which of the two visions is true. The question rather has to do with how man can live and flourish. The Epicurean materialist vision is not only empty, it empties: its great adverb is “only.” The mind is only the brain, and the brain is only a neural machine. Good and evil are solely social constructs. Human male and female are merely ideological projections.

Richard III expresses the materialist nihilism in his immortal and vain address to his few loyal adherents before the Battle of Bosworth Field:

Conscience is but a word that cowards use,

Devised at first to keep the strong in awe:

Our strong arms be our conscience, swords our law!

If there is no God, says Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov, all things are possible. They are possible, we suppose, but we cannot make them meaningful. Meaning cannot be forced, like a hothouse plant. Hence when Ivan begins to lose his sanity and is visited by the devil—a projection of his approach to nihilism—it comes in the form of a shabby middle-aged gentleman, a slick of sentimentality above a hollow of empty laughter, laughter without joy.

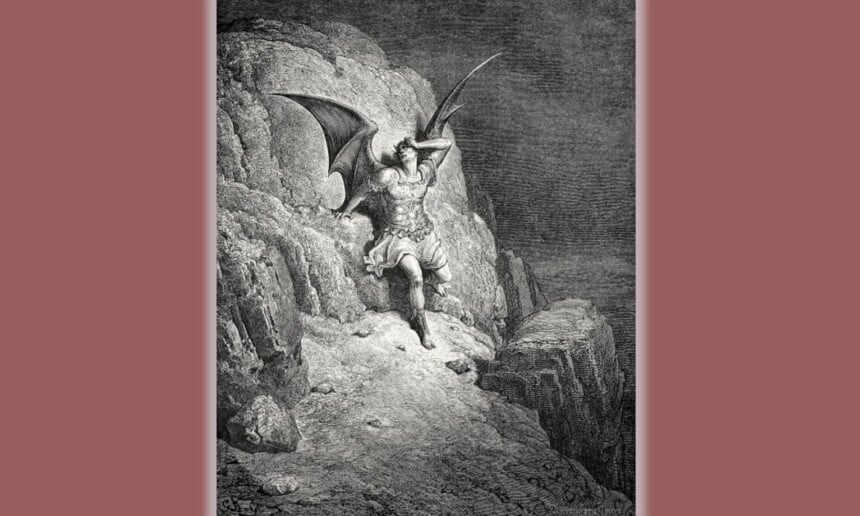

Satan wandering about the earth in the beginning, says Milton, “Saw undelighted all delight, all kind/ Of living creatures, new to sight and strange.” He sees their kinds, in their blessed particularity, their finite forms. He is too powerfully struck, intellectually if not existentially, by their beauty, the beauty wherewith God endowed them when he created them, each according to a certain nature. But instead of declaring, “How good it is that you exist,” he intends to destroy them, to involve or envelop them in his own turn away from being. This destruction requires the transgression of barriers, of definitions, of the blessed boundaries that make a thing what it is, as opposed to what it is not. Thus Satan’s entrance into Eden is an attack upon being:

Due entrance he disdained, and, in contempt,

At one slight bound high over leaped all bound

Of hill or highest wall.

Milton had found the same insight—that what is evil is both transgressive of finite forms, and ontologically empty, emptying those who embrace it—in his schoolmasters, the Renaissance poets Torquato Tasso and Edmund Spenser. Call it a violation of oneness or wholeness. When Tasso’s Satan summons up “the variegated gods of the abyss,” foils for the Trinity and for the unity of the Church, the demons who respond, though they come from classical mythology, are notable for their being neither flesh nor fowl:

Here you would see thousands of squalid harpies,

thousands of sphinx and centaurs and pale gorgons,

of all-devouring Scyllas groined with wolves,

thousands of snorting hydras, hissing pythons,

of chimaerae vomiting out their bitter flames,

of Polyphemuses and Geryons,

and all strange monsters never seen or known,

a rabble of discordances in one.

Spenser imagines, in his epic poem Faerie Queene, the demon Lechery in the parade of the seven deadly sins at the House of Pride. Lechery is a ladies’ man who knows all the arts of flirtation and seduction, but beneath the suave show, he is just an ugly walleyed fellow riding on a goat, whose bones are eaten hollow with syphilis, “that rots the marrow and consumes the brain.” His deeds are empty in themselves, and they evacuate the souls of others:

Inconstant man, that loved all he saw,

And lusted after all, that he did love,

Ne would his looser life be tied to law,

But joyed weak women’s hearts to tempt and prove

If from their loyal loves he might them move.

Spenser would not be surprised by the sexual ennui that has brought us the so-called “open” marriage, an emblem of a people who must be stung to arousal with the nettles of the new—which turns out to be old and weary—and the bold— which turns out to be timid and craven and self-protective. Safe sex, indeed: safe from meaning.

So too with the “trans” in trans-gender. It is a bridge to and from what are regarded as no-places, no-things. We may say all day long that it is biologically impossible to turn a boy into a girl. The biological impossibility does not matter, because the creatures themselves, the boy and the girl, are not acknowledged in the first place. Modern man, having denied that there is any meaning in created things, finds that his own mind falls to ruin, and he can no longer affirm any meaning in his own body, his sex. He is far from being grateful that there are such creatures as boys and girls. He is made wary and snappish by reminders of that fact. At best he retains a superficial appreciation for their peculiar forms of handsomeness. But he has been taught to acknowledge nothing more—not the far sight of the boy on the bow of the ship of life, or the deep tenderness of the girl who is made for protecting what is small and infinitely precious.

Think of how strange it is, this self-willed denial of male and female. “Binary,” sneers the feminist, as if there were something simplistic about the basis of all complex life upon earth. One wonders, has she ever seen a boy? Has she ever dwelt upon how beautiful a girl is? How can anyone with eyes and mind and heart not be struck by the beauty of the binary?

“These things,” says the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, referring to clouds and hills, so much less glorious than man, “these things were here and but the beholder / Wanting.” We do not behold, and so we do not see. A dog sees, but a man can behold a thing as an object of contemplation, look upon it in the way an artist might, or as God in the beginning “saw the light, that it was good” (Genesis 1:4).

But there is nothing more boring than boredom itself. If you are bored by Bach, the deficiency is not in Bach, but in you. Imagine owning a painting by Rembrandt, say “The Return of the Prodigal Son,” and wanting to “improve” it by pasting a big toothy grin on the kindly and wise old man welcoming the boy home. Imagine gazing up at Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” and wanting to gussy up the colossal first man with lipstick. Vandals have nothing of their own, so they smudge and smear whatever they can lay their hands on. It gives them a thrill, one that lasts a moment or two, before boredom settles in again. How different they are from those who can receive the gift of beauty! So wrote John Keats in his poem “Endymion”:

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness, but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

By contrast, the “transgressive” finds the thing of beauty to be an offense, a reminder of his own insignificance and poverty of soul. Think of it. If you are a man, alive to the beauty of woman, it never occurs to you that you could become a woman, unless you were quite mad. You would know that all your attempts would be no more than acts of vandalism against your own sex, and an insult to the other. A woman who pumps her body full of androgens and cuts off her breasts does not become a man. She becomes a sad and pathetic wreck, a mutilated woman, looking superficially in one or another sense like a man, but not really; ugly, but not in an honest, homely way; soft-bodied and small-voiced; muscled, but not as a man is. She is neither flesh nor fowl.

The motive is not desire, but boredom, or hatred of the goodness of your own sex. It is not so much that the transgressor wants very much to belong to the other sex, as that he wants very much not to belong to his own. He says he is trapped in the “wrong” body, and he suggests that he may do away with that body by violence if he is not granted the escape he wants. He does not accept his sex as a gift, but then, no one else does, either. It is a thing, to be used, like a tool, for procuring what you want. But since there is no aim beyond what the vagaries of desire and the imagination can arouse, he no sooner attains the desire than he finds himself restless again. There is an old Latin saying, Omne animal post coitum triste est sive gallus et mulier. Every animal is sad after coitus except the human female and the rooster.

I have said that I was not going to determine here which of the two visions, that of a created world, or that of brute and meaningless stuff, was true. But I can say which of the two leads us deeper into knowledge. Lucretius boasts that it is his which does so:

A little work will guide you—you shall know.

One point illuminates the next, nor will

The blind night steal your path, till you have read

Nature’s last truths. Knowledge: a torch for knowledge!

But in the matters I have been discussing, Lucretius has been proven wrong. The evacuation of sexual meaning has not inspired us to probe more deeply into what men and women are; the very object of the search is denied. What new insight into the nature of woman has the feminist discovered? She denies the nature of woman. She is affronted by it, irritated by it. But imagine, just for a moment, that maleness and femaleness are inestimably precious gifts conferred upon us by our Creator. Great and salutary beauty then lies waiting for us to behold, to prize, to search into, and to learn from our God-given natures.

Image Credit: above: Satan from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, engraving by Gustave Doré (public domain)

Leave a Reply