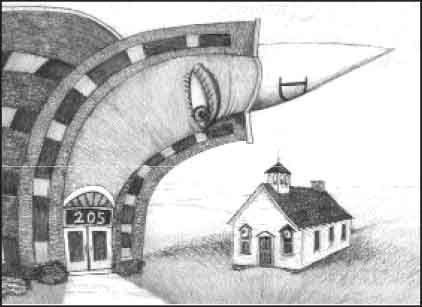

“School cuts would hurt neediest kids,” the headline in the local Gannett paper proclaimed. With the spring primary just days away, the administration of Rockford School District 205 was urging the public to pass the third education referendum in a row. This one would allow the district to issue $23.5 million in bonds and use the revenue to pay back tax protesters who had successfully fought judicial taxation during the district’s 12-year school-desegregation lawsuit. Despite the unusual circumstances, however, the rhetoric was the same as that used in referenda battles across the country: “Think of the children!”

The district administration claimed that drastic cuts would need to be made if the referendum failed: no more sports, computers, drama, band, and no more tutors for children who needed extra help. All of the major cuts had one thing in common: They would eliminate programs that bring children to school early and keep them there until late in the day. In other words, these programs allow mothers to work without having to shell out extra money for daycare, and they keep young children off of the street.

The administration played its cards well: On March 19, the referendum passed by approximately 500 votes, out of 34,000 cast. Though District 205 already spends almost $10,000 per student, local voters had shown their willingness to provide a quality education to the 27,000 children enrolled in District 205—or so the district administration declared. A new, brighter day in Rockford public education had begun.

“During the summer of 1837, in a log cabin standing on the southeast corner of the intersection of East State and Second Streets, the history of the Rockford schools began. Miss Eunice Brown, conducting classes for six pupils that year, served as the community’s first teacher.” Thus writes Charles Espy, a former superintendent of schools for Winnebago County, describing the dawning of the first day in Rockford education in his 1967 book, The History of Public Education in Winnebago County. The “era of the itinerant tutor” (“an institution never very satisfactory in a social sense and very spotty as to results,” Louis Bromfield wrote in The Farm) had passed. Parents demanded a more stable educational structure for their children, and it emerged in three forms: first, private schools, such as Miss Brown’s, which often held their classes in the teacher’s home; later, starting in 1857, public schools controlled, variously, by township, city, and county authorities; and, much later, parochial schools. While, in some areas of the East Coast and South, the duty of education moved naturally from the home to the church, a strong Yankee influence led the Midwest to follow the New England model of public education.

From the beginning, the rising tide of public education was designed to lift all boats. Bromfield’s Jamie favored public schools over the traveling schoolmaster not simply because they could provide a better education for his children, but because “what troubled Jamie most was the fact that under this system the poorer children of the County received no education whatever and grew up without learning to read or write . . . ” State constitutions established public education as a universal right, and state statutes authorized local governments to levy property taxes to fund schools. Rockford’s initial levy in 1857 of one mill per $100 of assessed value covered the cost of building schools as well as hiring teachers and a few administrators.

The late 1800’s were a time of remarkable growth in public education across the Midwest, and the number of school districts multiplied rapidly in Winnebago County, while, within districts, building programs established the network of neighborhood schools that school consolidation and busing have destroyed. The one-room schoolhouse, usually white or stone rather than red, became a common sight in the countryside.

By 1903, when the first school consolidation in Illinois took place right here in Winnebago County, there were 124 separate school districts in the county, many consisting of just one or two schools. Their numbers decreased rapidly: By 1920, the county had consolidated down to 110 districts; by the time of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), there were only 39 districts left. Over the next 40 years, Brown would accelerate school consolidation and the destruction of neighborhood schools; busing, however, was more a consequence of school consolidation than a cause.

By the time Espy published his History of Public Education in Winnebago County in 1967, there were a mere 25 school districts left in the county. District 205 was now larger than the city of Rockford. Two decades later, as the federal court prepared to intervene, District 205 had gobbled up another nine school districts, and it now covered essentially the entire southeastern corner of Winnebago County.

School consolidation paved the way for the social engineering that destroyed public education in the second half of the 20th century; what, however, led to school consolidation? We know the arguments that were made by its proponents: Bigger schools offered greater opportunities for students and allowed for a standardized curriculum; larger districts had more resources at their disposal; smaller districts and one-room schools did not fit with the latest educational theories, which required separate grades and multiple teachers. (In the 1930’s, the Rockford school district adopted a high-school hour model for elementary schools, an experiment it later abandoned.) Still, in Illinois and throughout the Midwest, school consolidation needed to be approved by the voters. Why did parents accept the arguments of the “experts”?

In The Farm, Bromfield writes of “the inflated reverence for schools and academies and universities which caused them to spring up like mushrooms everywhere in the Middle Western country during the second half of the nineteenth century.” He ascribes this attitude to “a generation or two which . . . had had little opportunity for education and so sought exaggerated advantages for their children and grandchildren.” That inflated reverence was applied to educated men as well as educational institutions, and it was not confined to a generation or two. In fact, as the general population became better educated, the reverence for education grew rather than diminished, and the popular cult of the “expert” took root.

It is one thing to believe that operating a nuclear-power plant requires a certain level of knowledge that the average person does not possess; it is quite another to become convinced that someone else, by virtue of his education, can direct the education of your children better than you can (even if he might be able to teach your children better). The “experts” can cry, “Think of the children!” but parents have been thinking of their children from time immemorial and managing, largely, to make wise decisions on their behalf without the benefit of “expert” advice. Relying on “experts” and acquiescing in their plans often is simply the flip side of a failure of nerve. The irony is that the very system that convinced parents to entrust the education of their children to more highly educated experts was undermined by the centralizing programs of the very “experts” to whom the parents had ceded their authority.

Charles Ingalls would have understood the problem. When the Ingalls family was living in DeSmet, Dakota Territory (the period covered by Laura Ingalls Wilder in Little Town on the Prairie), Charles was a member of the school board—the only one, as Laura tells us, who had children in the school. The other board members seem to be men who are concerned about the general extension of education, and they are probably better educated than Charles, but Charles is there because he is “Pa.” When the teacher, Miss Wilder (the sister of Laura’s future husband), loses control of her one-room schoolhouse for several days, the board appears before the students, and Charles is the only one to speak.

Slowly and weightily, Pa said, “Miss Wilder, we want you to know that the school board stands with you to keep order in this school.” He look sternly over the whole room. “All you scholars must obey Miss Wilder, behave yourselves, and learn your lessons. We want a good school, and we are going to have it.”

When Pa spoke like that, he meant what he said, and it would happen.

The room was still. The stillness continued after the school board had said good day to Miss Wilder and gone. There was no fidgeting, no whispering. Quietly every pupil studied, and class after class recited diligently in the quiet.

As we have moved from Miss Wilder’s one-room schoolhouse to the massive Columbines of today, what have we gained? American public education lags behind the rest of the civilized world, and we turn to Chinese and Pakistanis to fill our high-tech jobs—not because they will work more cheaply, but because they can actually do the math. Even on the most basic level, American public education is a failure: The literacy rate, once over 90 percent, is now around 75 percent and falling. We spend more money per capita on public education than at any time in our history, and as many as 30 percent of students cannot read or write at grade level. (Those are official figures; in reality, the percentage may be higher.)

Where do we go from here? One thing is clear: An elected school board of seven members cannot possibly redirect a bureaucracy that oversees a district of 27,000 students and a budget of close to $300 million. During Rockford’s 12-year battle with the federal courts, only two of the candidates who were elected on vows to fight judicial taxation and restore local sovereignty came anywhere close to living up to them. The rest, upon election, lost their nerve when the “experts” told them that the only way out from under federal control was to go along with judicial taxation and racial quotas.

A new day in Rockford public education did not dawn on March 19; on that day, we simply passed another way station on the road to destruction. The conservative panaceas—school vouchers, charter schools, school prayer—ignore the underlying problem. Johnny praying the Our Father at the beginning of the school day will not make his parents more involved, and transferring him to a charter school or a private school under a voucher program may even lead his parents to think they can be less involved, because Johnny is now in a better environment. While the homeschooling movement arose out of a recognition that parents should direct their children’s education, it still needs to strike the right balance between directing and teaching (which might be done by others), and, in this regard, the rise of homeschooling cooperatives is a hopeful sign. Ultimately, American education will only revive when parents recover sufficient nerve to act as Charles Ingalls did. Let’s think of the children.

Leave a Reply