“E’ la morte di una civilizazione.” (“It’s the death of a civilization.”) These were the words of the Vatican official who told me the following sad story at the beginning of September. It seems that, after the heat wave of August, hundreds of the cadavers of the lonely urban old folks of France were being kept in the city morgues. When their vacationing families returned, many of them reacted with amazement and resentment when they learned that they were expected to pay for the burial of their own dead. As the accurate, if historically tardy, judgment of the papal diplomat implied, these “loved ones” had left behind survivors who were, shall we say, the living dead. “Vive la France,” indeed. Read on, for the cheerless end of the story given here has a long prologue.

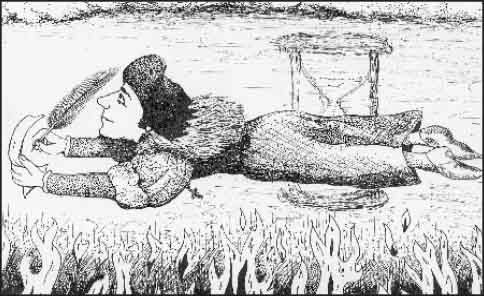

In his informative and consoling masterpiece of historical research The Stripping of the Altars, Eamon Duffy drew the conclusion that the most distinctive characteristic of late-medieval English piety on the eve of the 16th-century religious upheaval was the devout remembrance of the dead. There was not a monastery, collegiate chapter, parish church, or cathedral that did not have a daily round of Masses and dirges for the deceased; woe to the cleric who was negligent in this regard, for lay folk were devoutly attentive that not a single candle go unlit or one nocturne of the Psalter go unsung from the list of their endowed observances. Liturgy, however, was not the only expression of piety toward the departed. There were anniversary distributions to the poor, foundations of hostels and schools, pilgrimages, bridge and road building, all in suffrage of the deceased—and indulgences, of course, for all these public works. Moral instruction had the purifying and corrective penalties of Purgatory as a principal illustration, and iconography presented to the eyes of the faithful an intermediate state full of souls of all sorts and conditions, and even many a tonsure, veil, miter, or coronet could be descried in the fires.

Such “popular religion”—as the concrete charity and piety of Catholic Christians is called by those who do not believe in it or who see it, for the most part, as a necessary crutch for the unprofessional (that is, those not trained in seminaries or universities)—was purified, according to the usual account, by the Catholic and Protestant Reformations. Christian humanists and reformers turned to a practice of religion based on the Bible and the Fathers, freed of wild oriental and Celtic accretions.

St. Thomas More, whose credentials as a reform-minded humanist are beyond dispute, as his ironic Utopia bears out, could be expected to have provided a critique of the luxurious cult of the departed that flourished in his time. In any case, his good friend Erasmus could have. More’s writings tell a different tale, however. In The Supplication of Souls, published in 1530, More has the robust, graphic, and morally concrete faith of a medieval man, and this perhaps explains best why he had to become a modern martyr. In this work, now felicitously back in print, the attentive reader will find that he was a prophet of both the means and the effects of modernity. His faith in the eschatological world to come infused his judgment with a seer’s insight into the historical world to come that we—and not just the French urban proletariat—are “living” now.

In 1529, a certain Simon Fish (whom, perhaps, I may with some poetic justice claim as an ancestor, since I have some Fish ancestors who made it from England to South Carolina in the 18th century) published a pamphlet in the Low Countries entitled A Supplication of Beggars. In this work, intended for mass distribution in England, he speaks in the person of the beggars of England, made so because of the wealth and rapacity of the clergy. The beggars attack devotion for the dead as the source of riches for the friars and as the impoverishment of the needy. They call for a bill to deprive the massing priests of their means and, with the confiscated money and property, to aid the poor. More responds to the beggars’ arguments, both theological and legislative, in The Supplication of Souls, itself written in the person of the souls in Purgatory. He offers not merely an apology for the dogmas of Purgatory and the priesthood but an argument ex effectibus for the old order and a prediction of the character and methods of the new. For the former, I refer the reader to his work, where a complete apology for these dogmas will be found. Here, I will deal with the latter, namely, his prophecy of what I have called the means and effects of the new social order that was beginning in his day and is now reaching its full development as, with breathtaking insincerity, it proclaims its own end in “postmodernity.”

Fish’s pamphlet is archetypally modern. It is a mass-media product that uses statistical arguments that are both based on and elicit emotional responses meant to determine the judgments of its public. More recognizes this approach and refutes it on its own ground, as the following passage bears out. His commonsense argument can serve as a model for the undoing of the positivistic, the inherently irrational, and the passionate “reasoning” of the social sciences:

So let us begin where he begins, where he says that the number of such beggars as he pretends to speak for—that is, as he himself calls them, the “wretched, hideous monsters” at whom, he says, “scarcely any eye dare look,” the “foul, unhappy sort of lepers and other afflicted people, needy, helpless, blind, lame, and sick, who live only on charity”—has by now so badly increased that all the alms of all the wee-disposed people of the realm are not half enough to sustain them, but that by sheer constraint they die of hunger. . . .

If we were to tell you what number there was of poor sick folk in days gone by long before your time, you would be at liberty not to believe us. However, neither can he, for his part, set out before you a list of their names. So we must, for both our parts, be content to refer you to your own time—and not even starting from childhood (of which people forget many things when they get much older), but just the days of your good remembrance. And, doing so, we suppose that if the sorrowful sights that people have seen had left as great an impression still remaining in their hearts as the sight makes of the present sorrow that they see, people would think and say that they have in days gone by seen as many sick beggars as they see now. For as for other ailments, their incidence is, thank God, no higher than it was in times past. In fact, thirty years ago the number of beggars with syphilis was five times what it is now. If anyone wants to say that they see this otherwise, we will get into no big argument over it, since we lack the names to prove it with. But surely whoever will say the contrary will, we suppose, do so either just because they want to or else because the same thing is happening with their sight as happens with folk’s ability to feel. Whatever pain folk feel right now, they whine at; but what they have felt in the past, they have more than half forgotten, even if they felt it quite recently. Which makes someone who has just a little blister on one finger think this suffering much greater than the pain of a big swelling that covered the whole had little more than a month ago. So that as for this point of the number of sick beggars having so badly increased so recently, although we will refrain from saying to him what we could say, we will yet be so bold as not to grant it to him till he brings in some better thing for his proof than his bare word for it.

In place of the anecdotal emotionalism of statistics, More offers the reality of the whole cosmos created by God as a refutation. This is a brilliant intuition, even though it is presented as simple catechism. Mass-media arguments assume only the reality of their audience, not the objective authority of the witness of the whole of reality. More’s suffering souls speak:

But surely if what he calls “all the world” is all that God ever made, then there are three parts of it that know the contrary. For we dare be so bold as to guarantee you that in heaven, in hell, and here among us in purgatory, of everything that this man so boldly affirms, the contrary is quite clearly known. And if by “the world” he means only persons among you who are living there on middle earth, he yet will perhaps find in some part of the world, if he conducts a thorough search, more than four or five good, honest persons who never heard any mention of the case. And of those who have heard of it and know much about it, he will find plenty—and in particular, we think, the King’s Grace himself—who will affirm that of all which he has here in so few lines affirmed, not one is true; that they are lies, every one of them.

More sees in the attack on the veneration of the dead and on the property of the priesthood a cloak for the passions, the will to power, and the death of true charity. He turns to predict the effects that will follow in society if Mr. Fish’s pamphlet were to attain its end, in a clear prophecy of the coming servile state. Here are the words that More’s holy souls address to the “compassionate conservatives” of the 16th century:

Now, some landowners may perhaps suppose that their case will not seem the same as that of clergy because they think that the clergy have their possessions given them for purposes which they do not fulfill, and that if their possessions happen to be taken from them, it will be done on that basis, and so the lay landowners are out of danger because, they think, such a cause or basis or perception is lacking and cannot be found in respect to them and their inheritance. Certainly if anyone, whether priest or lay person, has lands in the giving of which has been attached any condition which he has not fulfilled, the giver may with good reason take such advantage of that as the law gives him. But on the other side, whoever would advise princes or lay people to take from the clergy their possessions on the basis of such general allegations as that they do not live as they should, or do not use their possessions well, and would claim that therefore it would be a good deed to take them by force and dispose of them better—we dare boldly say to whoever gives this argument, as now does this beggars’ spokesman, that we would counsel you to take a good look at what would follow. For as we said before, if this bill of his were put through, he would not fail to provide you soon after, in a new supplication, plenty of new meritless arguments that would please the people’s ears, arguments whereby he would endeavor to have lords’ lands and all honest folk’s goods confiscated from them by force and distributed among beggars. Of whom there would, by this strategy that he devises, come about such an increase and growth that they could in a hasty, makeshift way [make] up a strong party. And as surely as fire always creeps forward and tries to turn everything into fire, so will such bold beggars as this one never cease to solicit and procure all that they can—the despoilment and robbery of all who have anything—and to make all people beggars like themselves.

Yet More’s intention is not simply to frighten the propertied class and to gain its support of the clergy. He perceives that the coming revolution is rooted in the rejection of divine things. How many times and in how many places have his words been fulfilled to the letter, and in how many times and places to come!

For once having destroyed the clergy, they could after that . . . with their false faith infect and corrupt the people, causing them to set the blessed sacraments aside, to pay no heed to holy days and fast days, to disdain all good works, to rant against and ridicule holy vowed chastity, to blaspheme the venerable fathers and doctors of Christ’s Church, to mock and scorn the blessed saints and martyrs who died for Christ’s faith, to reject and to deny the faith that those holy martyrs lived and died for . . . with contempt for God and all good people, with obstinate, rebellious attitude toward all laws, rule, and governance, and with arrogant audacity to meddle with everyone’s money, everyone’s land, and everyone’s affairs that have nothing to do with them. . . . For eventually they will gather together and assemble themselves in bunches and in big crowds, and from asking go to just taking alms for themselves, and under pretext of reformation (telling everyone who has anything that they have too much) attempt to make new divisions of everyone’s land and substance, never ceasing, if you suffer them, till they make everyone the beggars that they themselves are, and in the end bring all the realm to ruin, and this not without butchery and foul, bloody hands.

Thomas More’s world—the world inhabited by the souls in Purgatory, longing for Heaven and resurrection as they benefit from the prayers and bodily works of the living, feel the consoling presence of the angels and saints, and rejoice that they have escaped eternal Hell—is a world of order, based on a hierarchy of participation and communion. The world he foresaw is the revolutionary world of private voluntarism and public manipulation fueled by the sensual appeal of the mass media—a world in which, as the psalmist says, “no one is left to bury the dead.”

On September 3, 2003, at Thiais, in the periphery of Paris, in the municipal paupers’ field, at a ceremony from which all media representatives were barred, the president of France and the mayor of Paris presided at a burial of 50-some old folks who had been overcome by the August heat of indifference and whose bodies had not been claimed. There were poems and Bach on strings, and the name of each was read out, already engraved in the large stone slabs over each one’s grave—a state funeral, reserved only for heroes. The third of September is the feast of St. Gregory the Great, the Middle Age’s principal patron of devotion for the dead. The poor, their rulers, solemn music, the absence of the cynical: Was all this a sign of hope or just a sign that the end has truly come? One thing is certain: St. Thomas More knows the answer.

Leave a Reply