We were on the practice field preparing for a team that ran the option. Our scout team was running the upcoming opponent’s offense. To our surprise, the scouts executed the option perfectly, which left our outside linebacker frozen halfway between the quarterback, cutting off the block of a tight end, and a trailing halfback arcing toward the sideline. “What the hell you doing—splitting the distance? You’re neither fish nor fowl,” bellowed one of our coaches. “You have to commit!”

Whenever I hear of dual citizenship, I think of the coach’s words. Today, we have people who are neither American nor foreign but something between, not fully committed to any particular country. I was stunned a decade ago when Strobe Talbot declared in Time that nationhood and citizenship had become obsolete. I am no longer stunned. There is a growing trend toward dual citizenship, which suggests that the fierce loyalty and complete identification with the United States that I always thought was simply part and parcel of being an American is on the wane. Moreover, there seems to be no stigma attached to dual citizenship. This was not always the case.

When the Japanese began immigrating to the United States early in the 20th century, they were viewed with suspicion for several reasons; prominent among them was dual citizenship. The immigrants themselves were ineligible for American citizenship and remained solely Japanese citizens, but their American-born children were citizens of both the United States and Japan. Under the 14th Amendment, by virtue of their birth on American soil—the principle of jus soli—the children were American citizens. Under Japanese nationality law, as codified in 1899, the children were Japanese citizens if their fathers were Japanese—the principle of jus sanguinis. In 1924, under pressure from the United States, Japan began requiring Japanese resident in America to register the births of their children within 14 days at a Japanese consulate in order to acquire dual citizenship for the children. It is not surprising that many Japanese failed to register their children within the allotted time. What is surprising and significant, however, is that nearly 40 percent of all children born after 1924 were duly registered. Then, too, the requirement seems to have been designed more to quiet fears in America and to have been ignored in Japan. Japanese authorities continued to refer to all Japanese living in America (and elsewhere overseas) as doho (“countrymen”) and considered them subjects of the emperor. As a teacher in a Saturday Japanese school in Hawaii said to his nisei pupils in 1939, “You must remember that only a trick of fate has brought you so far from your homeland, but there must be no question of your loyalty. When Japan calls, you must know that it is Japanese blood that flows in your veins.”

These dual citizens were commonly sent to Japan to be educated. By 1940, over 20,000 American-born Japanese had been educated in Japan. Known as kibei, they were dual citizens in every sense. Not only were they fluent in Japanese, but many preferred its use to English after they returned to the United States. They were also steeped in Japanese history and culture and were supporters of Japanese expansion in the Far East. They could hardly be distinguished from young militarists in Japan. All of this was troublesome for fully Americanized Japanese who feared the kibei would cause problems for them in the United States. The Office of Naval Intelligence was interested in them as well. Lt. Cmdr. K.D. Ringle had been gathering intelligence on the kibei for months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. In January 1942, he submitted a report that said:

[T]he most potentially dangerous element of all are those American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have spent the formative years of their lives, from 10 to 20, in Japan and have returned to the United States to claim their legal American citizenship within the last few years. Those people are essentially and inherently Japanese and may have been deliberately sent back to the United States by the Japanese government to act as agents.

The kibei made a prophet of Ringle. They established the Sokoku Kenkyu Seinen Dan (Young Men’s Association for the Study of the Mother Country) and the Sokuji Kikoku Hoshi Dan (Organization to Return Immediately to the Homeland to Serve) and called for all American-born Japanese to renounce their U.S. citizenship. Ultimately, 5,589 officially did so. Most of the renunciants were housed at Tule Lake Segregation Center in northeastern California, just below the Oregon line. There they greeted the rising sun, cried “banzai,” blew bugles, drilled, celebrated on Pearl Harbor Day, rioted, and waited to be expatriated to Japan.

Then came an ironic twist. During the early summer of 1945—just after Okinawa had fallen to American forces—many of the renunciants applied to the Department of Justice to have their renunciations withdrawn. The number of applications increased dramatically after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Suddenly, it was not so bad to be an American. The Justice Department, however, responded by announcing that “all persons whose applications to renounce citizenship have been approved by the Attorney General of the United States, will be repatriated to Japan.” The renunciants contacted Wayne Collins, a San Francisco attorney and a representative of the American Civil Liberties Union, who immediately filed suit in federal court asking that the renunciants be set at liberty, that the deportation order be rescinded, that the renunciations be voided, and that renunciants be declared U.S. citizens again. When Collins first filed the suit, there were 987 plaintiffs. Within weeks, there were 4,322. The litigation dragged on for several years. Eventually, the plaintiffs prevailed on the deportation issue but failed to regain their citizenship, remaining in the United States as “native American aliens.”

The final irony came in 1988. The renunciants were included among those who received $20,000 each from the American taxpayers for “human suffering” as part of the Civil Liberties Act. Renunciants who had not tried to regain their U.S. citizenship and who had not fought deportation received the money also: It was sent to them in Japan.

During the 1930’s, there were more than 20,000 nisei living in Japan. Upward of 7,000 of them served in the Japanese army or navy. Some were drafted; others volunteered. One of the first to fight for Japan was Los Angeles native Shigeru Matsuura, who served with the Kwantung Army in Manchuria and was decorated for valor in the Manchurian Incident in 1931. Several dozen others followed. At least four nisei, including three from the greater Los Angeles area, died when the Kwantung Army’s 23rd Division was mauled by Russian forces on the Manchurian border. Japan’s Neutrality Pact with Russia in 1941 ended the fighting in Manchuria until August 1945. In the meantime, Japan established a POW camp at Mukden. The camp’s paymaster and interpreter was San Francisco native and Tokyo Imperial University graduate Eiichi Noda. Included among the prisoners were 1,400 American soldiers from Corregidor. By the time they arrived in 1943, most were too emaciated and debilitated to work, but some 200 became slave laborers for the Manchukuo Machine Tool Works. Their taskmaster was another San Francisco-born nisei, Yoshio Kai.

By the late 1930’s, however, most nisei were assigned to units fighting in China. Japanese newspapers in Hawaii and California encouraged American-born Japanese to serve the emperor. In 1938, the Jitsugyo no Hawaii urged:

Japanese of Hawaii! There’s absolutely no need to feel any hesitation. What’s wrong with serving your ancestral land? Are not those who vacillate about contributing money at this time of national emergency being unpatriotic? Look! Has not our Army Minister sent a respectful letter of thanks even for those who contributed fifty cents? Isn’t this the flower, the sincerity, the essence of our Japanese military?

The same newspaper and others aimed at Japanese in the islands and on the Pacific Coast carried stories about the valor of nisei fighting in China. The newspapers also ran obituaries of fallen nisei, usually with photographs of the young men in their Imperial Army uniforms. Torao Morishige, a nisei from Honolulu and a sergeant in the Imperial Army, was killed in action in China. His obituary quoted his mother as saying that his last words to her were, “If news of my death should come, please rejoice.” His brothers were quoted as saying that they were now going to Japan to join the army. (And I had always thought that the first Americans to fight in China had names such as Bob Neale, “Tex” Hill, Jack Newkirk, “Black Mac” McGarry, Chuck Older, R.T. Smith, “Whitey” Lawlor, and Johnny Donovan—the men known as the Flying Tigers.)

Nisei served Japan throughout the Pacific and Southeast Asia during World War II. Many were interpreters and guards in prison camps. Prisoners were often astounded when a Japanese soldier spoke to them in English with an American accent. Although there were some exceptions, the American-born Japanese mistreated, tortured, and killed American prisoners just as their Japanese-born comrades did. British and Australian prisoners suffered the wrath of nisei as well. At a camp in southern Thailand, a Japanese-American interpreter—described as having a lame leg, American-style glasses, and an American accent—and several guards beat a British sergeant major with bamboo and teak poles until he was unrecognizable and insensible. Then they stood him in the sun for five days.

The most notorious of the prison guards was Tomoya “Tom” Kawakita. Born in Calexico to Japanese immigrant parents, he left California for Japan in 1939 at the age of 18. He graduated from Meiji University after the war had erupted and served the emperor as an interpreter and guard at Oeyama prison camp on Honshu. Prisoners called him “Efficiency Expert” for his effective methods of torture. He seemed to delight in inflicting the greatest possible pain. He also forced prisoners to beat one another and then tortured those he thought had not struck blows with sufficient force.

Oeyama was established next to a nickel mine not by accident: The prisoners were used as slave labor. Kawakita saw to it that the Americans, already weakened by malnourishment and disease, worked until they dropped. He taunted them continually. When American bombers began hitting Japan and the prisoners suspected that the end was near, Kawakita told them, “We will kill all you prisoners right here anyway, whether you win the war or lose it.” He later said, “You guys needn’t be interested in when the war will be over, because you won’t go back. You will stay here and work. I will go back to the States because I am an American citizen.”

Kawakita was right about himself. Somehow, he reentered the United States without arousing any attention and enrolled at the University of Southern California. Then, in the fall of 1946, at a Sears department store in Boyle Heights, William L. Bruce, a former Army artilleryman who survived the fall of Corregidor, the Bataan Death March, and imprisonment at Oeyama, recognized Kawakita. “I was so dumfounded,” said Bruce, “I just halted in my tracks and stared at him as he hurried by. It was a good thing, too. If I’d reacted then, I’m not sure but that I might have taken the law into my own hands—and probably Kawakita’s neck.” Bruce recovered in time to follow Kawakita outside and copy the license number of the car in which the former guard drove away. Bruce notified the FBI, and Kawakita was soon in custody.

Charged with treason, Kawakita was represented by Morris Lavine, who called himself the “attorney for the damned.” Lavine’s clients included mobsters Mickey Cohen and Johnny Roselli and union boss Jimmy Hoffa. At the trial, Kawakita suddenly became a born-again Japanese citizen, claiming that he had stopped being an American citizen when he went to Japan and, thus, owed allegiance only to the emperor. The testimony of two-dozen American prisoners who had suffered under Kawakita was to the contrary. So, too, were Kawakita’s actions after the war. Nonetheless, U.S. District Court Judge William Mathes instructed the jurors that, if they determined that Kawakita genuinely believed he was no longer an American citizen, they must find him not guilty of treason. On several occasions, the jurors told the judge that they were hopelessly deadlocked. Finally, they returned a verdict: Kawakita was guilty of 8 of 13 counts of treason. Judge Mathes, who had seemed to make the jury instructions as favorable to Kawakita as possible, then imposed the severest penalty for treason—death—and said, “Reflection leads to the conclusion that the only worthwhile use for the life of a traitor, such as this defendant has proved to be, is to serve as an example to those of weak moral fiber who may hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the United States.”

Kawakita appealed his conviction to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco. William J. Kelleher, a federal prosecutor, drafted the U.S. government’s response to the appeal. While Kelleher was working on his brief, Bruce and two other former Oeyama prisoners called on him. “Me and the boys had a little meeting last night,” declared Bruce. “And we want you to know that if he ever gets out, we’ll be waiting for him.” Kelleher said he was greatly relieved when the appeals court upheld the conviction, by a 3-0 vote.

Kawakita then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case was heard in 1952. The question before the Court was where the allegiance of a dual citizen lies when war erupts between the two nations that claim his loyalty. “Of course, a person caught in that predicament,” said Justice William O. Douglas, “can resolve the conflict of duty by openly electing one nationality or the other.” Kawakita had chosen neither, ruled the Court in a 4-3 decision (with two abstentions). Instead, he had chosen to maintain his U.S. citizenship while serving Japan. Then, when faced with charges of treason, he wanted the freedom to claim Japanese citizenship only. “One who wants that freedom,” Justice Douglas stated, “can get it by renouncing his American citizenship. He cannot turn it to a fair-weather citizenship, retaining it for possible contingent benefits but meanwhile playing the role of the traitor. An American citizen owes allegiance to the United States wherever he may reside.”

Kawakita’s story does not have a happy ending. In 1953, President Eisenhower, responding to appeals from the Japanese government, commuted Kawakita’s death sentence to life in prison. Ten years later, President Kennedy ordered him freed on the condition that he be immediately deported and never allowed to reenter the United States. His three sisters, who spent time in a relocation center during World War II, became eligible for $20,000 each as a result of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. William Bruce and his fellow prisoners received nothing but the G.I. Bill.

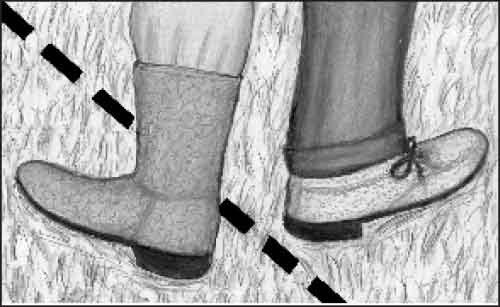

Untold numbers of Mexicans now claim dual citizenship, encouraged to do so by Mexican President Vicente Fox. As a result, California and other states will soon witness the spectacle of Mexicans voting in both U.S. and Mexican elections without leaving the United States. The border between the United States and Mexico has not quite been erased, but it certainly has been smudged. Like the Japanese doho, President Fox says that Mexicans are Mexicans even if they reside in the United States and have become U.S. citizens. Like Tom Kawakita, many Mexicans want the freedom to chose which-ever citizenship is convenient at the moment. There are now hundreds of murderers and other felons who have committed crimes in California and fled to Mexico. More than 60 murderers from Los Angeles County alone are south of the border, including Armando Garcia, who gunned down sheriff’s deputy David March during a traffic stop. Garcia and the others understand that their chances of arrest in Mexico are slight. And Mexico recently announced that it will not extradite any criminal suspect who faces a sentence of death or life in prison to the United States.

Even Mexican illegal aliens have now acquired a form of dual citizenship. Mexican consulates in California and Illinois (and in other states) have begun issuing “matricula consular” identification cards to Mexicans residing there. Although legal immigrants have no need for such a card, several California cities, including San Francisco, and Illinois cities, including Chicago and Rockford, have announced that they will accept them as formal identification for all purposes. The city of Oxnard, California, which is now nearly 70 percent Hispanic, announced in January that it will begin accepting the cards. “I’m in favor of it,” Oxnard Mayor Manuel Lopez said. “Identification is needed for everything these days, and it will certainly make it easier for people to do business with the city.” Mexican Consul Fernando Gamboa said his Oxnard office issues about 1,000 matricula-consular cards per week. If nothing else, the numbers reveal something about the size of the illegal-alien population in Ventura County. Republican Elton Gallegly, who represents much of Ventura County in Congress, argued that the cards should not be accepted as formal identification because they are issued by a foreign government and the United States thus has no control over who receives them. Ironically, it was Gallegly’s statements that were considered controversial, not those of Mayor Lopez. Strobe Talbot must be proud.

An entire population of dual citizens with divided loyalties is developing in the American Southwest. I suspect this is happening throughout the United States with several population groups. America is rapidly becoming a kind of enterprise zone for the world’s populations—not much more than a place to make money. Becoming an American now means little more than residing within certain lines on a map. Acquiring wealth and possessions defines “the American dream.” Somehow, I think the Founding Fathers had more in mind than this. Time for William Bruce and the boys to take some action.

Leave a Reply