California was imagined and named before it was discovered. In 1510 in Seville there appeared a novel that would have Fabio on the cover today. Written by Garcia Ordóñez de Montalvo, Las sergas de Esplandián is a romance of chivalry that vividly describes the adventures of a fictitious Christian knight, Esplandián. In defending Constantinople against the Muslim invaders Esplandián is aided by an army of amazons from an island in the Western Sea. The island abounds with riches and wonders and is called California.

Montalvo’s novel was a best-seller and inspired explorers to search for California, not because the idea of a paradisiacal land in the Western Sea was something newly introduced by Montalvo but because it tapped into an old Celtic myth that had currency in Europe for centuries if not millennia. The Celts believed that somewhere to the west—of wherever they currently were—was a paradisiacal land. They pushed westward for centuries until one tribe, the Gaels, reached Ireland, probably during the third century b.c. By the fifth century a.d., Irish monks were voyaging into the Atlantic in hopes of finding paradise. They found Iceland and Greenland, and perhaps North America. Vikings followed their path. But no paradise.

During the 1530’s Hernando Cortés renewed the search that others had abandoned centuries earlier. One of his expeditions, without the conquistador himself, reached Baja California but found only a barren land inhabited by a few scattered bands of primitive Indians. Although other expeditions determined that Baja was not an island but a peninsula and no riches (other than a few pearls) were discovered, the name California began to appear on maps. Most thought the paradisiacal California must lie farther to the north.

In September 1542 Juan Rodríquez Cabrillo, a Portuguese soldier of fortune in the service of Spain, led an expedition that sailed into San Diego Bay, effecting the European discovery of California proper. Spain did nothing with Cabrillo’s discovery or with the discoveries of other Spanish commanders for more than 200 years. Nor did England do anything with the discoveries of Francis Drake, who sailed the California coast during 1579 and camped at Point Reyes, three-dozen miles northwest of the Golden Gate, for five weeks.

It wasn’t until 1769 that Spain got around to settling California, doing so only because of the threat of Russian encroachment. It was a half-hearted effort at best. By 1773 California was guarded by only five missions and two presidios, manned by a skeleton force of 61 soldiers and 11 friars. The first pueblo, San Jose, was founded in 1777, and the second, Los Angeles, in 1781. Few Spaniards or Mexicans were interested in the new province. Spain tried to populate California by having the mission fathers Hispanicize the locals, peoples such as the Chumash. It was largely a failure.

Spain quickly lost interest in California. When the Russians built a fort on a bluff some 20 miles north of Bodega Bay, Spain reacted only by sending an order to the California governor to have the fort removed. The governor did nothing, and Spain did nothing. The Russians occupied Fort Ross through the end of Spanish rule and nearly through the end of Mexican rule, abandoning the post only because it became an economic liability.

If Californians were generally unconcerned about the Russian settlement at Fort Ross, they were also mostly unconcerned about the Spanish American wars of independence, which began erupting in 1808 and continued until 1821. Other than a raid by part-revolutionary, part-pirate Hippolyte de Bouchard, California saw no action. When word came of the success of the Mexican Revolution—in 1822, a year after the fact—Californians merely lowered the imperial banner of Spain and raised the new Mexican flag.

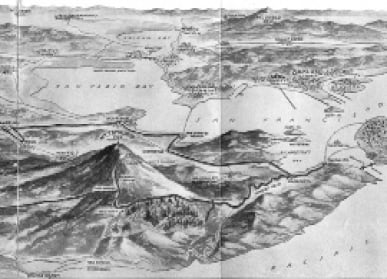

Mexico had no more interest in California than did Spain, not bothering to send a governor to the far-flung territory until 1825. In the meantime, Californians ruled themselves. Other than Indians, there were only a few thousand of them. No settlements penetrated California’s interior or reached north of Sonoma. The capital of Monterey had no more than 700 people, and Los Angeles fewer than 600. There was no San Francisco, only a small village called Yerba Buena with some 180 inhabitants. These Californians were an independent bunch. At different times during the 1830’s and 40’s, aided by American mountain men and sailors, they revolted against Mexico and declared California a “free and independent state.” For a couple of years a Californian would control what little government there was. For a year of two, an appointed Mexican governor would rule. There were occasions when both a Mexican and a Californian would govern simultaneously from different capitals. There were times when nobody governed.

By the early 1840’s most of the leading Californians, who thought of themselves as Castilian Spanish, not Mexican, and called themselves Californios, were advocating either annexation to the United States or independence with an American protectorate. They understood that Mexico had neither the desire nor the resources properly to govern or protect California. The Russians lived with impunity at Fort Ross, and California’s settlements were vulnerable to any of the great naval powers. In 1842 Commodore T.A.C. Jones, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet—all seven ships—misinterpreted his orders and captured Monterey with almost no opposition. He promptly declared California annexed to the United States. Two days later he discovered his error and returned California to local authorities.

During the 1830’s and 40’s, Americans, in ever-greater numbers, arrived in California. Hundreds of sailors, artisans, and traders settled in coastal communities, and hundreds of frontiersmen, on ranches and farms in California’s interior. Unlike the Spanish or the Mexicans, the Americans fully appreciated the potential of the region. Men known as boosters published pamphlets extolling the virtues of the province and inviting Americans to come and settle. By 1846 Americans made up a quarter of the non-Indian population of California, which barely surpassed 10,000. Mexico only infrequently, and only with great difficulty and very limited success, sent small parties of Mexican settlers to California. Moreover, Americans were responsible for most of the business and trade of California. Even without the Mexican War, California would soon have become part of the United States. When the war did erupt, Commodore John Sloat sailed into Monterey Bay and captured and annexed California without opposition. There were some skirmishes in the southern part of the province but only because an overly aggressive and brusque Marine officer offended the pride of the ruling-class rancheros.

A week before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally concluded the Mexican War, a moody, eccentric character named James Marshall would change the course of history. On the morning of January 24, 1848, Marshall looked into the race of a lumber mill he was constructing in the Coloma Valley, 40 miles east of his boss’s settlement of New Helvetia, today’s Sacramento. He thought he saw something glitter. He reached down and picked up a yellow lump of metal about the size of a small pea. Then he saw another. The lumps were heavy and, when he hammered them, soft and malleable. He hurried to the cabin where his construction crew was having breakfast and exclaimed, “Boys, I believe I have found a gold mine.”

It would be weeks before word of the strike started spreading in California and months before it reached the states. At first most people thought it a hoax to lure the gullible westward. As evidence mounted, though, a frenzy seized the nation—and then the world—and the rush to California was on. By 1850 the population had grown tenfold to 100,000, allowing California to skip the territorial stage and enter the union as a state—the Golden State as it was popularly termed. By 1853 there were a quarter-million residents. By 1860, nearly 400,000. With the arrival of Americans during the Mexican War, Yerba Buena became San Francisco but still boasted only 800 residents by March 1848. By the summer of ’49 it had 5,000. A year later, 25,000. Two thirds of these immigrants were Americans. Ireland led in contributing foreigners to California, followed by Britain (including Cornwall, Wales, and Scotland), Germany, China, Australia, and France.

Until recently, this rush to the Golden State continued unabated. When mining declined there were booms in timber, irrigation agriculture, real estate, tourism, and oil. Through the 1950’s there were oil fields, and oil derricks, over much of Central and Southern California. During the 1920’s and into the 1930’s California not only drilled more oil than any other state but produced one quarter of all the oil produced in the world. The motion-picture and aircraft industries came to California early in the 20th century and contributed mightily to what was rapidly becoming one of the world’s most diversified and powerful economies. The Dust Bowl drove tens of thousands of Okies (the term was applied to migrants from not only Oklahoma but also Texas and Arkansas) to California. World War II only accelerated population and economic growth, and dramatically increased the small number of blacks in California—not only did women come into the workforce to replace white men who were overseas fighting, but so too did blacks.

By the end of the war there were seven or eight million Californians. A little more than a year later I came into the world. As a child I found California a paradise. My family lived in Pacific Palisades, a small community perched on bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Behind us were the Santa Monica Mountains. The beaches were rarely crowded. The local mountains less so. Small groups of us kids would hike for hours through canyons, over ridge lines, up the highest peaks—and never see a soul. We were unencumbered by rules and regulations of a park service. The mountain land was privately owned but untouched by development. We took our slingshots and BB guns along with us. The older guys plinked with their .22 rifles. From Sullivan and Mandeville canyons on the east to Topanga Canyon on the west we roamed through thousands of acres of our own private park, catching frogs and turtles in creeks and spying deer, coyote, and bobcats, and occasionally a mountain lion, darting in and out of the chaparral. Old guys in the community—they were in their 40’s and 50’s!—told us about the bear that were in Santa Ynez Canyon back in the 20’s.

We killed rattlesnakes and made hatbands of the skins. We’d attach the rattles to lanyards and proudly wear them to grammar school. Darryl, an older kid with an enterprising spirit, got the bright idea that he would capture rattlesnakes and milk their venom for sale in producing antivenom. He had a small collection of rattlesnakes and his business was expanding when he was bitten on the arm attempting to capture still another rattler. He staggered to the Coast Highway and collapsed. A sheriff’s deputy picked him up and took him to a substation in Malibu, evidently thinking the incoherent kid was drunk or on drugs. Darryl’s arm quickly swelled to twice its normal size, and another deputy finally recognized that Darryl was a snakebite victim. He was rushed to a hospital and surgeons opened his arm from shoulder to wrist. He narrowly escaped death. Someone took photographs of the surgery. When I took zoology as a freshman in college, there in our textbook’s chapter on herpetology were photos of Darryl’s arm.

The point breaks seemed reserved to us local surfers. Sunset, Topanga, Malibu, and Latigo were ours. The older guys forced outsiders to show us locals great deference. Nonetheless, in those days, except on summer weekends, there were more than enough waves for everyone. There simply were not enough people in California to ruin the pristine nature of surfing. Nor were there enough people to spoil the Sierras. My first trip to the real mountains of California occurred during a family vacation in 1952. We stayed for several days in Sequoia and several more in Yosemite. There were no crowds and no reservations required for the choicest of campsites. There were no RVs. Everyone camped in tents. There was also no thought of thieves. Campers left their tents and gear unattended while hiking or fishing or horseback riding. At sunset, “Where’s Elmer?” was called from camp to camp. When it turned dark in Yosemite, everyone in the campgrounds gathered to watch the Firefall, a spectacular several-thousand-foot-drop of flaming bark pushed off Glacier Point by rangers. The practice was ended in 1968 by some spoilsport in the park service.

By the time we were teenagers we were hiking portions of the John Muir Trail, which follows the spine of the Sierras for 230 miles. One summer a buddy, Dave Cochran, and I spent 12 days hiking the much higher and more spectacular southern half of the trail. Our mothers took a minivacation together, driving us to the end of one of the paved roads that lead into the Sierras and dropping us off. They spent a couple of days at a lakeside cabin before returning home, while we took off on a lateral trail that led to the Muir. Since we didn’t know exactly how many days it would take us to complete the hike, we would hitchhike home. At one point on the Muir Trail we went a day and a half without seeing another human being. Today, the trail is crowded and a wilderness-entry permit with exact dates of travel must be obtained months in advance. All we did was grab our Kelty packs and go.

Hunting also requires great time and preparation today in California. Years ago we would simply get a license and deer tags at our local sporting goods store and go. Hunting most game required no special tags at all. One could hunt anywhere it was allowed. Now hunters, months in advance, must compete in a drawing for selected areas. We couldn’t have imagined such a thing. Nor could we have imagined all the gun laws that would be enacted on both the state and federal level. Back then nearly everyone I knew had guns sitting in their houses and many had a pistol on top of the road maps and next to the flashlight in the glove compartment of their cars. No one thought a thing of it. We could buy guns at the sporting-goods store in a few minutes or in a few days through a mail-order catalogue. Ammunition was sold not only at the sporting-goods store but at the markets and was usually found sitting next to the can openers and Blue Diamond long-stem wooden matches. I can’t imagine what the reaction would be today at the checkout stand in a California market if boxes of .30-06 and .45 ammo were riding the conveyor belt between half-gallons of milk and cartons of ice cream. Despite the ready availability of guns and ammo in the 1950’s and early 60’s, crime was a fraction of what it is today.

The urban sprawl that now characterizes California had only just begun during the 1950’s. Rural areas were only minutes away. In the Palisades, horses were found in many backyards, especially those houses bordering the canyons. My older sister, like most girls then, was horse crazy. She rode from when she was a young girl. She and her girlfriends would ride their horses around town, which still featured more vacant lots and open fields than buildings. A dirt street, which was called the Bumpy Road, ran through the town’s small commercial district. A few miles up the Coast Highway there were regular rodeos held at Crummer’s Field, near today’s Malibu Civic Center. There were riding and roping teams and horse shows everywhere in California.

At our grammar school we had a cow in a small agricultural area. We learned to milk the cow and churn the milk to make butter. In junior high we had an agricultural class in the seventh grade. We took field trips to one of the local dairies, Edgemar, which sat on the floodplain of Ballona Creek and was bordered on three sides by farm fields. During the mid-1960’s the city of Los Angeles built a boat harbor there, Marina del Rey, and today the area is covered with commercial buildings and condos, revealing no hint of its agricultural and dairy-farm past.

Getting anywhere in California was facilitated by the best highways and roads in the nation—and traffic jams were only occasional nuisances. Today those roads are potholed and cracked, and terrible traffic is a daily reality in every urban area of California. Most of California’s infrastructure has a shabby appearance now. Public-works projects that took months to complete in the 50’s take years to complete now. California’s roads meant freedom to me. By the time I was 16 I had a motorcycle and was riding those roads with reckless abandon. With a riding buddy or two I would clock hundreds of miles over a weekend, mostly on back roads where it was rare to see another vehicle. No helmet laws then, and gas was a quarter per gallon for “ethyl,” which was the “premium” of the day. However, we usually indulged our bikes because of their high-compression pistons with the more expensive Chevron Custom Supreme. It seemed extravagant to pay 29.9? per gallon, but we thought the 103 octane was worth it. This grade of gas exists today only as racing fuel.

We also rode bikes built for flat track and TT racing on the fire roads of the Santa Monica Mountains—our backyard. Off-road bikes were unregulated and untaxed in California then, and the fire roads were only occasionally patrolled. In essence we had a racetrack minutes from our garages, and we rode and crashed like only adrenaline-pumped teenage kids could. The thrill was on. To do what we did then now takes hours of trailering motorcycles—registered and taxed by the state—to designated locations in the desert. Even then the riding is regulated by patrolling rangers.

Homes were relatively cheap in California. This was even true in today’s ridiculously expensive Pacific Palisades and Malibu. Modest houses in those areas generally went for $20,000 in the 50’s. Now, even after the recent crash in real estate, those same modest houses fetch $1.5 million. In the 50’s our teachers and mailmen could buy houses and live in the Palisades and Malibu. Today they would be lucky to rent a guest bedroom.

Much of this change for the worse has been a consequence of the dramatic growth in population. I was in high school in 1962 when it was announced that California’s population had reached 20 million. State officials bragged that we had surpassed New York as the nation’s most populous state. I thought it a dubious distinction. Now we have 37 million. There are problems beyond simple numbers, though. Until 1965 immigration was restricted to ensure that the ethnic composition of America did not change. I grew up with several immigrant families. Three came from Ireland, two from England, and one from Germany. The kids blended in almost immediately. The parents, within a few years. There were no problems of any kind. Moreover, these immigrants were generally well educated or skilled in the trades, and they immediately contributed to California’s tax base. They cost the state nothing—and no one conceived of the day when we would have to “press one for English.”

Unlike today, the illegal-alien problem was dealt with decisively during the 1950’s. Thousands of illegal immigrants had come into California during World War II to help fill the labor shortage, and many of these remained behind when the war ended. The numbers were miniscule when compared with today, but, nonetheless, an outraged public demanded action. In 1954 President Eisenhower appointed retired Gen. Joseph Swing to head the Immigration and Naturalization Service. A West Point classmate of Eisenhower and a veteran of the 101st Airborne, “Jumpin’ Joe” launched “Operation Wetback.” Wetback began in California in a coordinated effort of the Border Patrol and state and local law-enforcement agencies. Hundreds of officers swept through Hispanic neighborhoods, and hundreds more through agricultural areas. Within a year more than 100,000 illegal aliens not only in California but throughout the Southwest had been taken into custody and deported. To discourage reentry, buses and trains took them deep into Mexico. More significantly, more than a million illegal aliens, fearing arrest, returned on their own to Mexico.

Without the burden of illegal aliens and without the great costs of today’s welfare system and institutions of criminal justice, California in the 1950’s and 60’s consumed one-third less in taxes, proportionally, than the state does today. Yet, water projects, freeways, universities, state parks, and harbors were built and expanded and debts easily serviced. The budget was balanced, and California bonds were rated triple A. Houses were relatively inexpensive. The population was overwhelmingly native-born and white. Student performance was good. Crime was low. All this and a stunning natural environment made California a paradise—or at least as close as we can get to one here on earth. I can’t think of any place I would rather have lived. The climate is still the world’s best, the Sierras still stand tall, and the Pacific still laps the shoreline, but for everything else, all I can say is, you should have been here yesteryear.

Leave a Reply