Law professors like to debate among themselves which of the U.S. Supreme Court’s many opinions is the very worst. There has been a general consensus that the most loathsome is the one in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), in which the Court decided that the right to hold slaves in the territories was a “fundamental right” protected by the Constitution that could not be abridged by Congress. That decision was, in effect, overruled by the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. Almost equally bad was the Court’s decision in Lochner v. New York (1905), which held that the same notion of “substantive due process” that prevailed in Dred Scott meant that, if a state mandated maximum-hours laws for workers, it impermissibly interfered with a constitutionally secured freedom of employers and employees to enter into contracts. That understanding of the Constitution went by the board with the advent of the New Deal when the Court, faced with the overwhelming 1936 electoral victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and perhaps intimidated by FDR’s railing against the Court’s “horse and buggy” views of the Constitution and his threatening to pack the Court with nominees more favorable to his views, broadened the scope of permissible state and federal regulation. Yet both Dred Scott and Lochner, as recent scholarship suggests, did honestly seek to reflect constitutional principles that were inherent in the 1787 document, which was, after all, ratified by the representatives of the people themselves.

Another candidate for worst decision by the Court is Roe v. Wade (1973), which somehow found in the 14th Amendment’s guarantee that no state could deprive its citizens of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law” a right to terminate a pregnancy before fetal viability. This remarkable 7-2 decision has puzzled scholars, who simply cannot convincingly argue that matters of pregnancy or abortion involve historically protected constitutional rights, since the basic structure of the Constitution leaves matters of domestic law to the states.

We now have another candidate for worst decision: Obergefell v. Hodges, decided 5-4 on June 26, which declared that the same provision of the Constitution involved in Roe v. Wade also prohibits any state from limiting marriage to one man and one woman.

How seven of nine justices could decide that a woman’s “right to choose” trumps the right to life of an unborn child is still baffling to me, and perhaps Roe v. Wade will prevail as the great example of Supreme Court error, but in terms of usurpation of the role of popular sovereignty in our republic, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Obergefell will be difficult to surpass.

This is not the first time that Justice Kennedy has engaged in freewheeling jurisprudence. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which upheld the right to terminate a pregnancy first enunciated in Roe, while acknowledging Roe’s essentially flimsy, if not nonexistent, constitutional basis, the plurality opinion for the Court contained a notorious passage, now universally attributed to Justice Kennedy:

At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Belief about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under the compulsion of the state.

These words are now known as the “mystery passage,” and Kennedy invoked them in his opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), in which he held that it was impermissible for a state criminally to punish consensual homosexual relations. They were invoked again in the opinion of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Goodrich v. Department of Public Health (2003), the first state supreme-court decision to hold that same-sex couples had a right to marry.

The meaning of the “mystery passage” is elusive, but taken in its broadest connotation it seems to suggest two things. First, that the highest goal of “liberty” ought to be protecting the freedom of individual choice, and, second, that in matters touching morality the state has no business interfering with whatever individuals want to do. Kennedy doesn’t explicitly reiterate the mystery passage in Obergefell, but the opinion is clearly written from a similar perspective. This perspective is fundamentally flawed, and so is the constitutional logic of the decision. Let’s take the constitutional and legal aspects of the decision, which have been the most prominently reported, first.

One searches in vain for anything like tight legal logic in Justice Kennedy’s 28-page opinion. It begins with the ringing words (somewhat similar to the mystery passage) that “the Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity.” One might have thought that the Constitution was about “we the people of the United States” securing the “blessings of liberty” to themselves and their posterity, but, for Justice Kennedy, the Constitution is about protecting the “identity” or, to employ a word he uses eight times in his opinion, the “dignity” of the individual. Still, Kennedy understands that he is required to show that the right to marry a person of one’s own sex is, in fact, a “specific right” protected by the Constitution. Since the Constitution says nothing about marital rights, this is a formidable task.

Kennedy makes no effort to ground the right to same-sex marriage in the text of the Constitution, but seeks to establish the importance of marriage as a protected right by turning to history, where he finds that “the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy”; “the right to marry is fundamental because it supports a two-person union unlike any other in its importance to the committed individuals”; “it safeguards children and families and thus draws meaning from related rights of childrearing, procreation, and education”; and “this Court’s cases and the Nation’s traditions make clear that marriage is a keystone of our social order.” There is no difference, Kennedy explains, between the application of these aspects of marriage for gay or straight people, and, thus, even though “The limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just . . . its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest.”

The bottom line, for Kennedy, is that based on the historical importance of marriage, the right to marry is fundamental, and no individual can be deprived of that right simply because of his choice of marriage partner. As he puts it, “Under the Constitution, same-sex couples seek in marriage the same legal treatment as opposite-sex couples, and it would disparage their choices and diminish their personhood to deny them this right.” As in the “mystery passage,” liberty (what for Kennedy the Constitution is all about) inheres in “personhood,” and the state may not compel (or diminish?) it. This isn’t constitutional law; it’s more like the once trendy psychological notion of “self-actualization.” For Justice Kennedy (and, apparently, the four concurring justices—Stephen Breyer, Ruth Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor), constitutional law and self-actualization amount to the same thing.

I am not alone in finding Kennedy’s opinion unsatisfactory. In one of the rare instances in which every single dissenting justice wrote his own opinion to blast the majority, Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito individually exploded. Each reminds us of what we have now lost.

Roberts, as the chief justice, first in seniority, filed the first dissent, which is most striking for his summary of what the majority did and the simple question he asked:

[T]he Court invalidates the marriage laws of more than half the States and orders the transformation of a social institution that has formed the basis of human society for millennia, for the Kalahari Bushmen and the Han Chinese, the Carthaginians and the Aztecs. Just who do we think we are?

In simple words of judicial modesty, which Roberts himself has not always heeded—as he did not, for example when he twice rewrote provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to solve its legal and constitutional defects—Roberts stated that, “Under the Constitution, judges have power to say what the law is, not what it should be.” With commendable candor and accuracy the chief exclaimed that “the majority’s approach has no basis in principle or tradition, except for the unprincipled tradition of judicial policymaking that characterized discredited decisions such as Lochner v. New York.”

The senior associate justice, Antonin Scalia, was characteristically blunt. He confessed, in a footnote, that

If . . . I ever joined in an opinion for the Court that began: “The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,” I would hide my head in a bag. The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.

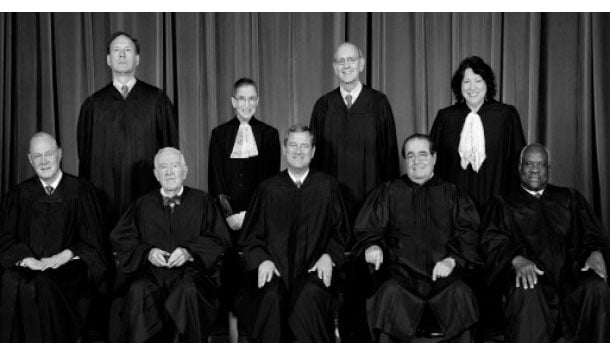

Scalia wrote, he said, “to call attention to this Court’s threat to American democracy.” What the majority did was to make clear that “my Ruler, and the Ruler of 320 million Americans coast-to-coast is a majority of the nine lawyers on the Supreme Court.” These were hardly a representative body—“tall-building lawyers,” who studied at “Harvard or Yale Law School,” all of them from the coasts, save one (Roberts, who grew up in Indiana), and not one of whom was an evangelical Christian or a Protestant of any denomination. (The Court now comprises six Catholics and three Jews.) “What really astounds,” he observed, “is the hubris reflected in today’s judicial Putsch.”

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, the justice most committed to implementing the understanding of the Constitution’s Framers, focuses on the majority’s essential misconception of the nature of constitutionally guaranteed liberties. Liberty, as conceived by the Framers, Thomas notes, is “freedom from government action, not entitlement to government benefits.” And if, as Justice Kennedy repeatedly claims, the case is about dignity, the majority and the plaintiffs have failed to understand that “the Constitution contains no ‘dignity’ Clause, and, even if it did, the government would be incapable of bestowing dignity.” Referring to the understanding of man inherent in the Declaration of Independence—which, for Thomas, has always been the foundational charter of national liberty—Thomas writes that it was “a vision of mankind in which all humans are created in the image of God and therefore of inherent worth . . . The corollary of that principle is that human dignity cannot be taken away by the government.” Moreover, “The government cannot bestow dignity, and it cannot take it away.” Thomas has a fundamentally different conception of constitutional rights than that articulated by the mystery passage or the majority’s opinion. For him, the Constitution does not exist to guarantee the maximum of individual expression or self-actualization but to protect the citizens’ ability to exercise the liberty that is part of our inalienable rights granted by our Creator, and, “As a general matter, when the States act through their representative governments or by popular vote, the liberty of their residents is fully vindicated.” When the government dictates the content of rights or creates new ones, that liberty suffers or is eradicated.

Justice Samuel Alito, the last of the dissenters, laments what he calls the majority’s “distinctly postmodern meaning” for liberty, one that essentially reduces it to the whim of five members of the Supreme Court. Alito strikes deeper, however, when he notes that the argument of the majority regarding marriage is that “the fundamental purpose of marriage is to promote the well-being of those who choose to marry.” As did the states who sought to bar same-sex marriage, Alito observes that, “For millennia, marriage was inextricably linked to the one thing that only an opposite-sex couple can do: procreate.” Alito recognizes that as a childrearing institution marriage is failing, since now 40 percent of all children born in the United States are born to unmarried women, but this does not diminish the fact that for millennia the stable two-parent procreative union was the fundamental building block of the social order. Further, those states that chose not to recognize single-sex marriage “have not yet given up on the traditional understanding. They worry that by officially abandoning the older understanding, they may contribute to marriage’s further decay.” For Alito this was a perfectly permissible public policy, and one that the Court had no authority to end.

Taken together the dissents make two powerful points. First, Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion, which wrests from the American people their previously existing right to decide for themselves how the institution of marriage should operate, is an act of truly stunning arrogance. As Justice Alito wrote, this decision “shows that decades of attempts to restrain this Court’s abuse of its authority have failed.” Second, and equally sad, is the impoverished philosophy or moral psychology the mystery passage and the majority’s decision reveals. In 1990, the great paleoconservative Russell Kirk wrote that our culture was in an advanced stage of decadence, and that

what many people mistake for the triumph of our civilization actually consists of powers that are disintegrating our culture; that the vaunted “democratic freedom” of liberal society in reality is servitude to appetites and illusions which attack religious belief; which destroy community [and] efface life-giving tradition and custom.

Kirk died in 1994, and if there are tears in heaven, Russell Kirk must be crying them, as he contemplates what the Court has done.

Leave a Reply