In the words of a 19th-century British nursey rhyme:

If wishes were Horses, Beggars would ride; If turnips were watches, I would wear one by my side.

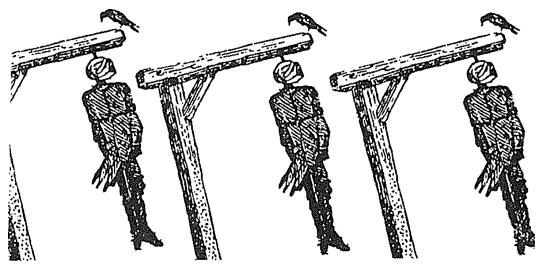

There is, it seems, a fairly influential group of rather strange persons out there who are wearing turnips and telling time; what’s unfortunate is that these persons, many of whom are designated “performance artists,” are not being taken as dreamers and/or moon-struck lunatics, but as bona fide enhancers of what was once popularly known as “Western Civilization.” The past tense is brought into play here because it’s unimaginable that the activities that these artists are involved in can in any way, shape, or form be construed as things done by human beings who have passed beyond that point in time called the neolithic period–and it may be a libel on our ancestors to yoke them with these contemporary life forms. Art, of course, is always paranormal: those works that can be figured “art” partake of something that is beyond the quotidian or ordinary. Consequently, artists in some ancient societies were considered to be divine madmen, seers into another dimension who were capable of bringing the sights or sounds from the outlying sphere back into the ordinary world. Obviously, anyone with that sort of reach was special. In time, however, the idea of the artist as an illuminated madman was replaced by that of the artist as outsider, or prophet. This has been the general scheme in the West since the advent of the Romantic period. Outsider status not withstanding, successful artists were often–for varying durations, the parameters of which were dependent on moods–hugged to the bosom of the society which they seemed to be in opposition to. They were feted, lionized, and otherwise rewarded for, ultimately, bringing out some of the finer aspects of what it is to be a human. Naturally, some artists, those who celebrated man with what were perceived as less palatable manners, retained more pure prophet status; these remained in garrets and workshops or left their homelands (possibly, just possibly, to be acknowledged there–or at home, once the domestics realized what they had lost). Art, with its uncanny ability to endure through time and space, would finally tend to emerge, even in cases when the makers were long passed. Commentators then elegiacally note that the artist in question was “ahead of his time,” a concept that is really more bizarre than anyof the artworks: a person can only be in and of the particular time that he is on this planet; otherwise, he wouldn’t be that person–or this wouldn’t be this planet.

In this era, the time of the outsider is no more. That is, thanks to/unfortunately because of (which side of the virgule you select indicates your ideological preference) a pervasive belief that pluralism is It, a truly giant achievement of late 20th-century man, there can no longer be any outsiders at large in our society. That may seem to be a rather comprehensive and therefore heady statement, but the backing evidence is as painful as it is obvious. Consider, for example, the case of those persons with communicable diseases. Once upon a time they were held off not merely at arm’s length, but were placed in quarantine. One of the most widespread, well known, virulent diseases about today is AIDS. Initially, people reacted strongly–and in some cases overreacted–to the merest hint of AIDS. But even before the virus behind it was isolated and announced (and it was repeatedly stated that a cure is still years away), reports emerged from San Francisco and other locations that indicated that pre-AIDS lifestyles weren’t simply being returned to, but embraced with a vengeance. Drug abuse is another form of disease. In an earlier time, addicts were isolated from or kept at the margins of society; now, statistics indicate that those who don’t partake of a narcotic in one form or another are more rare than those who do. Because of this status quo, the “artist” who is more concerned with cutting a figure than with creating genuine art finds himself in a very difficult position since there now seems to be no clearly drawn line that one can be beyond. Still, there are those who push beyond even imaginary boundaries and, what is more pathetic/disgusting, a modern, with-it claque that feels that it’s its duty not to praise the finer endeavors of creative man (an ancient, conventional task), but to celebrate the weird: “Let a thousand turnips tick!”

Consider the activities of one Chris Burden, a man whose “work” (along with that of Vito Hannibal Acconci, Laurie Anderson, and Nam June Paik) is central to The Art of Performance: A Critical Anthology, edited by Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas (E. P. Dutton; New York), a collection that is in no way critical of the so-called art, but which brings together shivers of excitement and shouts of praise. One of Burden’s works is Five-Day Locker Piece, which was executed at the University of California-Irvine during a five-day period in April 1971. Burden had himself locked into a 2x2x3-foot locker during that time. Later that year, in a gallery, Burden did Prelude to 220, or 110; itwas preceded by Shout Piece, during which he shouted obscenities at gallery patrons. About Prelude to 220, Burden said, “I was strapped to the floor with copper bands bolted into the concrete. Two buckets of water with 110 [volt] lines submerged in them were placed near me.” He added, “People were angry with me for the Shout Piece, so in 110 I presented them with an opportunity in a sacrificial situation.” Not only did no one–accidentally or otherwise–cause Burden to be electrocuted, but three others joined him for 220, during which they opened themselves up to death by electrified water. Other pieces had Burden shoving live wires into his chest (a short circuit saved him), dragging himself, while semi-nude, across 50-feet of broken glass, and having his body used for target practice.

Vito Acconci is similarly “artistic,” though less electric. In Security Zone (1971), for example, he walked around on a pier in New York; he was blindfolded and, he said, accompanied by “someone about whom my feelings are ambiguous, someone I don’t fully trust.” Acconci didn’t drown. Had he, the world of art (?) would have been spared Seedbed (1972), during which Acconci, secreted inside a hollow ramp in a gallery, performed onanism; an amplification system ensured that all those in the vicinity were aware of his activities. A recent report has it that Acconci telephoned the New York Times on a fairly regular basis in order to announce that his breathing is a work of art. In an essay on Acconci in The Art of Performance David Bourdon writes, “People who are not au courant with recent developments in contemporary art might think Acconci belongs in a padded cell.” Even those who are au courant might–and should–some to the same conclusion; he seems to be a type of madman sans divinity.

It might be concluded that the effects of those like Burden and Acconci are limited to a few members of a fringe group and to that group’s supporters in publishing houses and galleries. If only that were the case. Throughout The Art of Performance the name “Laurie Anderson” is uttered as if it has ritual power; she, a woman who seems–given her appearance and announcements–to start off the day by placing her head in a Cuisinart, is the great white hope of the performance art crowd. Their hope has paid off–for Anderson, anyway. Anderson, who is a musician (to use the term very loosely), recently put out an album titled Mister Heartbreak (Warner Brothers), on which she is accompanied by a number of persons, including that unmusical, aged favorite of the American potty-minded avant-garde, William S. Burroughs. Anderson, who could probably not survive if she didn’t have access to an electric outlet (for normal, not Burdenesque, purposes), diodes, amplifiers, and various pieces of silicon technology, talks over music that has jungle rhythms, music that wouldn’t be out of place on the soundtrack of something like Abbott and Costello Go to Africa. Nonetheless, at the time of this writing, the latter part of April, Mister Heartbreak is one of the top five albums on college campuses in the U.S.

Admittedly, Laurie Anderson’s success may be considered somewhat inconclusive as far as the pervasiveness of performance art is concerned. After all, big companies like Warner Brohers Records Inc., a Warner Communications Company, regularly pander to low and numb tastes. Moreover, college-attending individuals (sometimes–but not always–known as “students”) are barometers, in many cases, of nothing but the degree of adolescence retained by those who have physiologically passed out of that stage. Is there more widespread evidence of the influence of performance artists? Unfortunately, the answer is yes.

The efforts of artist (ah-hem) Nam June Paikin collaboration with musician Charlotte Moorman merit a chapter in The Art of Performance; Moorman’s execution of Paik’s Opera Sextronque (1967) is the main topic. Apparently, Moorman played a cello on a stage in New York while wearing nothing above her waist. Consequently, she was arrested, tried, and found guilty of performing a publicly indecent act–which shows how much New York has changed in less than 20 years, if nothing else. Paik, who is described as a “video artist” in a description written pre-MTV, was undoubtedly taking the show down through electro-optical means. Paik himself is no performing slouch. In 1981 he performed his Life’s Ambition Realized, which had him playing honky-tonk piano for a strip-tease act. There are, no doubt, bleary-eyed vets of numerous burlesque houses who would be delighted to discover that what they once did in the smoky, filthy, dank halls was really “art.” Currently, Paik’s work appears in prime time on CBS. Anyone who tuned in to see Charles Kuralt–a man who seems as dangerous as milk on The American Parade last season saw him on a set that was designed with the assistance of Paik. When the credits rolled at the end of the show, there was Paik’s name modified by “Design Consultant.” No back street galleries for Paik. Given this, would it be hard to imagine Burden as “special assignment editor” for That’s Incredible, Acconci as a regular on a Beat the Clock-type show, or Anderson as a hostess on a variety hour? If such things are possible–and it seems that they are–then the hands on our turnips should tell us that it will soon be too late for sanity.

Leave a Reply