American political and cultural elites—in their efforts to give us a revolutionary liturgical calendar—have now turned Juneteenth into a federal holiday. This smacks of the kind of “moral lesson” that Hollywood—or Hollyweird—and more generally the political left like to preach without checking facts. Juneteenth—or June 19—is not a good choice for celebrating the end of slavery.

According to the received wisdom, Juneteenth commemorates the day in 1865 when arriving Union troops informed slaves in Galveston, Texas, of the Emancipation Proclamation. Slaves in Texas were the last to be freed, simply because Texas was part of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Command, the last part of the Confederacy to surrender. But were slaves living in Galveston as ignorant of the proclamation as the story holds? It seems improbable if only because Union troops had occupied Galveston before 1865. The city was taken by the Union Navy on October 4, 1862 and held for nearly three months until a Confederate counterattack retook the town in January 1863. As is well-known, the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued in September 1862. It is highly unlikely that no Union soldier ever mentioned its contents to a single black person in a span of nearly a quarter of a year.

Even if that startling lapse occurred, it is hard to believe that slaves in Galveston, or the rest of Texas, had not learned of their emancipation before the war ended. East of the Mississippi slaves deep in Confederate territory knew of it and trekked hundreds of miles to seek the protection of, or even join, Union forces. Even those who did not take that step knew they had been formally freed. Moreover, Texas was, and still is, a border state. Even then, South Texas had a substantial Mexican minority, which (along with the German settlers) was not sympathetic to slavery or enthusiastic about the Confederate cause. (Runaway slaves in Texas fled south, not north.) Apart from the grapevine extending from the north, blacks in Galveston had ample opportunity, from 1863 on, to learn of their emancipation.

There is, however, another reason to dismiss Juneteenth as a proper date to celebrate the end of slavery. Eighteen sixty-five saw the end of slavery for black Americans, but not for everyone in American territory. Even after the Proclamation, slavery continued to exist for some years in the Southwest territories—overwhelmingly in New Mexico—where enslaved Amerinds may have approached 6,000 in the 1860s. This is known to specialists in the history of the Southwest, but—for reasons that are perhaps interesting—not to Americans in general.

Amerinds had sometimes been enslaved in the original Thirteen Colonies, as well, but that practice declined before the United States became independent, and died out after the Revolution. The slavery that existed in New Mexico was an inheritance from Spanish and Mexican rule, a byproduct of centuries of continual raiding back and forth between New Mexican Hispanos and their Pueblo Amerind allies on one side, and Navajos, Utes, and Apaches on the other, where both sides—but especially the New Mexicans—enslaved their captives. The resulting system survived the Mexican War and the American takeover, after which some Anglos acquired Amerind slaves.

Under both Mexican and American law, this slavery was not supposed to exist. It was never legally recognized but was a social fact. It was not quite like the slave system in the pre-Civil War South. Amerind slaves were cheaper and had some recognized rights. They could not be traded once acquired; they could contract marriages, after which they were freed; and their children were born free. Outrage at that system led to its abolition, along with that of peonage, in 1867. That was the real end of American slavery. Following its outlawing, federal agents were sent out to inform Amerind slaves of their freedom.

This aspect of American history might make an interesting movie or TV show. On second thought, considering how contemporary Hollyweird politicizes everything, perhaps such a production would not be a good idea.

Why is the whole subject of Amerind slavery in the Southwest and its abolition largely ignored? The reason may be that it does not fit the usual picture of relations between white “Anglos,” Mexican Americans, and Amerinds, in which the latter two groups are both seen as “victims” of Anglo oppression. It is an annoying fact that, Amerind slavery aside, the wars fought by the United States Army against the Apaches and Navajos were not, generally speaking, the result of Anglo land grabbing but conflicts taken over from the Mexican occupation. It was the Anglos who ended the slavery that the Mexicans had practiced at the expense of Amerinds. As these events, however, do not strengthen the left’s crusade against the white race, we may never see a holiday dedicated to celebrating this emancipation.

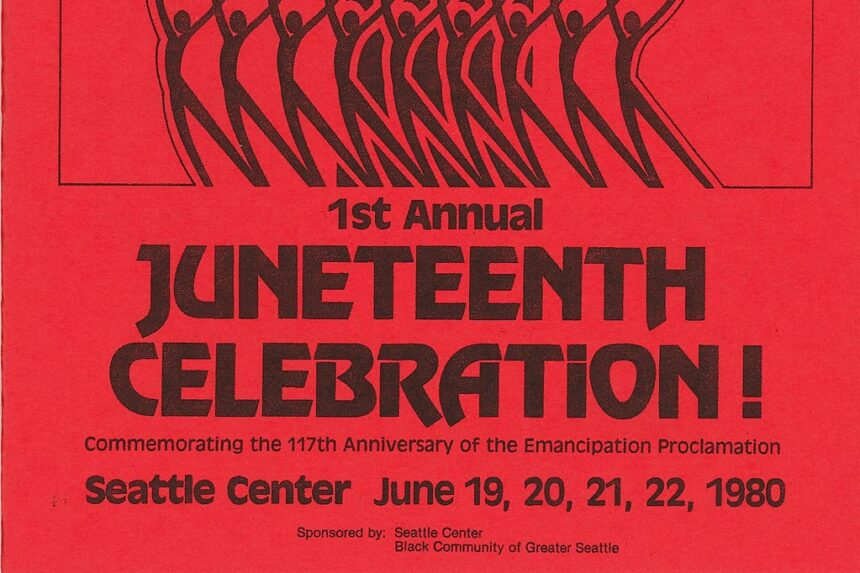

Image: Juneteenth Celebration program, 1980; by Seattle Municipal Archives (via Wikimedia commons / CC BY 2.0)

Leave a Reply