(This is the third in a series of articles on the cultural and political effects of the French Revolution. Parts I and II are here.)

The French Revolution as a great and glorious event, a defining moment in the upward linear march of progressive humanity, is the founding myth of the French Republic. The myth is firmly built into the foundations of French society, and embodied in the nation’s holiest holiday, Bastille Day, July 14. For those who want to understand more deeply the modern world, the holiday also provides a perfect opportunity to reflect on the Revolution and its implications.

In earlier articles, we have looked, without judgment and without commentary, at an array of psychopathological disturbances and sadistic depravity among the “revolutionaries.” We have also surveyed, in a brief manner, three strains of 19th-century Western critical thought regarding the Revolution and its aftermath. Now, in the concluding third part of this mini-series, we look at the state of modern and postmodern France as it sinks ever deeper into the quagmire of multicultural self-annihilation.

There are myths in the history of European nations that connect and unify, such as the Athenian narrative of its leadership of the Hellenic world in the Persian Wars, or the Spanish myth of the Reconquista as a linear process stretching from the early eighth century to the late 15th, or the Kosovo myth, which enabled the Serbs to endure four centuries of Ottoman darkness.

The myth of the French Revolution, by contrast, inherently perpetuates an emotional, moral, and intellectual schism within a great nation. It has been poisoning the bonds among members of the French polity for over two centuries. It was one of the direct causes of the Fall of France, in 1940. There are few French people of our time, however—or even in the two preceding centuries—who are able to bridge that gap. If some fleetingly succeeded, like the poet Charles Peguy appeared to do on the eve of the Great War, the feat was only temporary and fleeting. Georges Clemenceau’s assertion, during a debate in the National Assembly in 1891, that “the French Revolution is a block from which nothing can be taken away” remains, on the whole, untouchable, which makes for a horrid mix of the Revolution’s supposedly lofty ideals and its criminal practices. “The rights of Man and Citizen” remain inseparable from the Terror and its criminal perpetrators.

In the approved discourse of modern France, the horrors of the Terror were silenced, minimized, or justified by cynical games, and the apologists for the Terror were outraged by the “caricature” of the revolutionary leaders and the claim that they produced the “first Gulag.” Today, 233 years after the Revolution, there is no national reconciliation in France; there is no consensus on the historical truth, and there is no hope for one, because it is impossible to get a complete and faithful picture of the French Revolution based on the works of professional historians in France.

To this day, the nearly 700,000 victims of the Revolution—the Terror and the Vendée genocides combined, as they must be—are treated as the result of some force majeure. Jean-Noel Jeanneney, president of the 1989 bicentennial commission, fiercely defended the claim that the Revolution constitutes “a block.” He defended the guillotine as a “humanitarian advance” over earlier methods of execution. He likened the Terror of the Revolution to the comparatively tame “Second White Terror” of 1815, the restoration of the French monarchy. Documentary data from that period of “White terror” record that mobs lynched about 300 people in the south of France, that some Zouave soldiers were killed in their barracks, and that about twenty persons were more or less summarily tried and executed, including—famously—Marshal Ney.

The ratio of revolutionary victims to the “terror” victims in 1815 is 2,000 to 1. And yet the state-approved historian Jeanneney suggested equality between the two events. It is both factually and morally the exact counterpart to equating the Jewish Holocaust with Pinochet’s 1973 coup in Chile, or the victims of the Armenian genocide in Turkey with the casualties of the American intervention in the Bay of Pigs.

To their eternal discredit, French historians have not been able to rise above the sordid Dreyfusard discourse of the last decade of the 19th century. The so-called revisionism, which claims to provide an objective condemnation of both “left” and “right” versions of the Revolution, is especially hypocritical. The following statement by Francois Furet, a leading member of that camp, is illustrative of the mindset:

Basically, there are two points of view on the French Revolution that are incapable of shedding light on it. One is counter-revolutionary, and the other is Jacobin. Both seek to represent the French Revolution as a bloc that should either be rejected unconditionally, or else must be blessed in its entirety. That simplistic, or rather one-sided, dichotomy should be broken.

This pretense of even-handedness equalizes victims and criminals. The fact of the matter is that “counter-revolutionary” authors and historians, from Maistre (via Maurras) to Raspail, cannot be equated with the opposite camp. For starters, they never succumbed to the temptation to destroy historical archives out of fear that primary sources would not support their dogmas. But this is just what Albert Mathiez, the champion of “advanced” (apologist) history, did in 1919.

Another dishonest ploy of the late 20th-century “revisionists” involved their supposed rejection of the Marxist interpretation of the French Revolution. Of course, they were forced to reject Marx’s socio-economic explanation of the French Revolution, because it was clearly false. But when contemporary French quasi-revisionists condemn the Marxist interpretation—while carefully neglecting its mass-murdering terrorist character—they assume the pose of self-righteous Democrat-appointed judges in the United States who condemn, with almost equal zeal, violent black burglars and those white deplorables who dared defend themselves. By ignoring or downplaying the intimate link between the Revolution of 1789 and that of 1917, the “revisionists” absolve the Revolutionaries of any responsibility for the totalitarian bloodshed of the 20th century. Or else, like Furet, they grudgingly stress a link between the Revolution and Leninism but adamantly reject the Revolution’s connection with “genuine” Marxism.

To make matters worse, a few leftist French historians of some repute took on the task—more than half a century ago!—of interpreting the October Revolution as a Russian “Oriental” murderous idiosyncrasy, the result of Muscovy’s Asiatic proclivities. Tragic, of course, but it had nothing to do with the French Revolution or with Marxism itself. So they say.

All this posing on the part of the “revisionists” is merely a play to conceal their pro-Jacobin bias. In truth, the Revolution served all communists—from the Commune of 1871 to Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Pol Pot, et al—as a sociological and political model for their murderous endeavors.

In what sense then, if any, can it be said that the French Revolution constitutes a single block? If the French Revolution is an integral whole, what is the essential unity of that whole? And if it is not an integral whole, how can we distinguish the good from the evil in it? Is there a fatalistic strain in the Revolution that made all events inevitable, gruesome depravity included? Is a political or moral justification of the Terror possible? Did the Revolution have to happen at all? Was the whole episode a stage of human progress, in spite of everything, or was it the darkest event in European history until that time?

There are no credible answers to any these questions in today’s France, let alone elsewhere in the Western world. This does not mean that at least provisional answers are beyond the reach of the curious.

In smart Parisian circles, however, one does not even pose any of the difficult questions posed by critics of the Revolution. Vive la République!

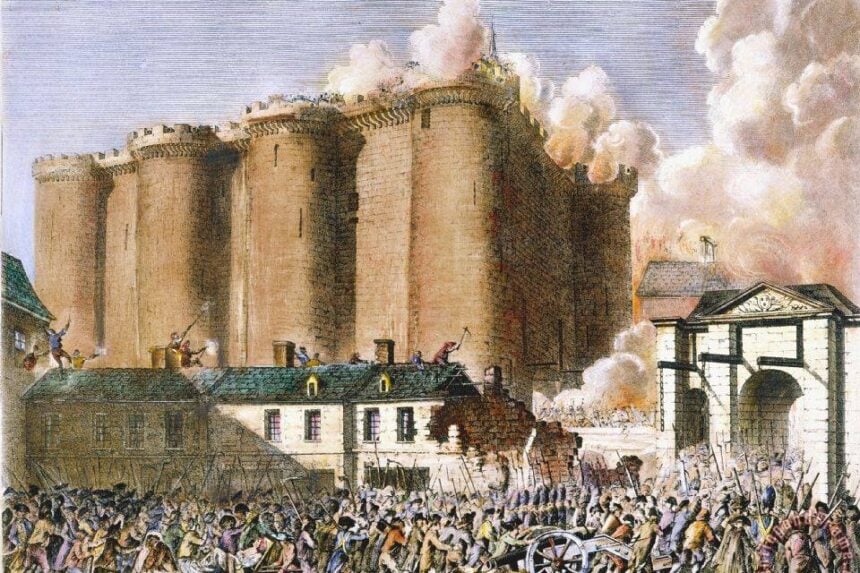

Image: French Revolution, 1789 painting,

(via Wikimedia commons / CC BY-SA 2.5)

Leave a Reply