Once, before giving a speech in Cincinnati, I met the chairman of the history department at Xavier University. I told him that I was going to talk about the sexual revolution and how it had been used to destroy Catholic political power in the period following World War II (the thesis of Part III of my book Libido Dominandi: Sexual Liberation and Political Control). My rendition of this chain of events culminated in a description of a July 1965 conference at the Vatican between John D. Rockefeller III and Pope Paul VI. During this meeting, organized by the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, then-president of the University of Notre Dame and a member of the board of directors of the Rockefeller Foundation, Mr. Rockefeller volunteered to write the Pope’s encyclical on birth control (knowing, I suppose, what a busy man the Pope was). In a letter composed shortly after the meeting, Mr. Rockefeller said that the Pope and “his church” were no match for the tide of history, which would sweep away the Catholic Church if it did not get with the contraceptive propaganda campaign being organized by Mr. Rockefeller’s Population Council.

The history department chairman’s jaw dropped, and he finally gasped, “You mean it was guys in a room somewhere?” Yes, as a matter of fact, it was. I had just named the guys, and — since the Pope holds audiences in certain chambers set aside for that purpose—the room as well. The chairman, however, was having none of it. If this were true, he wanted to know, why had none of the distinguished historians at the University of Notre Dame brought it out in their writings? The answer was simple: Notre Dame had committed itself to a certain view of history, in which the Irish (as the paradigmatic Catholics) came to this country and found discrimination, which they overcame by dint of hard work and a benign cultural climate that rewarded industry, talent, etc.

The type of history generally practiced in academia is known as “whiggish” history, which regards history as the result of broad forces. Ultimately, the broadest forces take predictable forms, and so history becomes the triumph of freedom over oppression and of the light of scientific understanding over the darkness of religious (read: popish) obscurantist superstition. Combining both variations in his recent history of the sexual revolution, John Heidenry claims that, during the 1960’s, “molecules of liberation coalesced.”

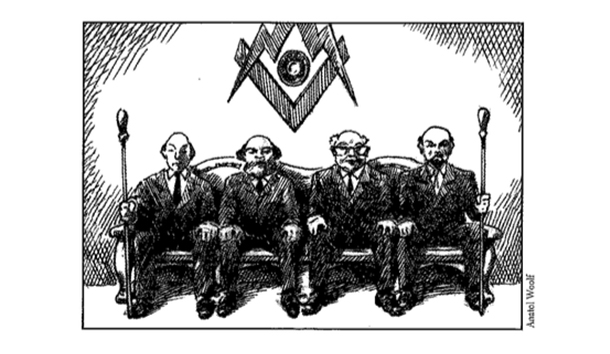

I mention this incident to show not just the extent to which whiggish history is the regnant dogma in academia these days, but also the extremes to which this ideology can be taken. Like Darwinism in biology departments and Lysenkoism in the psychology departments of Soviet universities, it has become a condition of employment. Whiggery is, in effect, the English ideology. Even when it clearly was guys in a room somewhere—Alexandra Kollantai was in the room when the October Revolution was being plotted by people she said could have fit on one sofa—the standard explanation for everything is broad historical forces. Those who believe otherwise are written off as “conspiracy theorists.”

There are two ways of dealing with the Whig position. The first is to reduce it to the absurd conclusion of the history professor from Cincinnati: Once we solve the problem of history, we are confronted by an architectural problem, namely, why people build all those rooms in all those buildings. The alternative is more realistic: Yes, there are people, and—yes—they do get together in rooms. In fact, the most powerful of those people often change the course of history by what they decide in those rooms. Lest anyone accuse us of battling straw men, let us confront the historical fact that the 18th century was known as the age of the secret society, and that the effects of one of those secret societies is with us still.

On May 1, 1776, Adam Weishaupt, a professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt in Bavaria, founded an organization he called the Club of the Perfectible. The name was later changed to the Order of the Bees, and changed again to that by which it is remembered today: the Order of the Illuminati.

The Illuminati might have remained the equivalent of a Bavarian fraternity house were it not for Weishaupt’s fortuitous meeting with a northern German aristocrat of extraordinary organizational capability. In 1780, while attending meetings at the Frankfurt lodge Zur Einigkeit, Weishaupt met Adolph Freiherr von Knigge, who immediately fell under Weishaupt’s spell. Knigge had joined a Masonic lodge of “strict observance” in Kassel in 1773, but—like many of his brother Masons—he was dissatisfied with the status quo, which involved elaborate rituals, constant bickering, and one group splitting off from another. In Weishaupt’s Illuminati, Knigge saw an instrument that would bring order out of chaos and reform the increasingly fractious Masonic groups.

With the conclusion of the Thirty Years War, Germany had been divided up according to the religion of its princes. Knigge, who became a member of the Illuminati on July 5, 1778, gave Weishaupt’s essentially Catholic and Bavarian organization access to the Protestant principalities in northern Germany; as a result, membership took off, jumping to 500 men throughout Germany. But the numbers tell only half of the story. Knigge added to Weishaupt’s following of university students by attracting aristocrats and influential bureaucrats and thinkers from across Germany, using existing Masonic lodges as a source of recruits.

A crucial event in this regard was the Wilhelmsbad Congress, a Masonic convention held near Hanau from July 16 to September 1, 1782. Upon returning from the congress, Henry de Virieu told a friend: “The whole business is more serious than you think. The plot has so carefully been hatched that it’s practically impossible for the Church and the Monarchy to escape.”

The idea would fail, however, because of strife within the Illuminati. Ironically, the Illuminist system of control led to the break. Knigge’s success in recruiting new members made Weishaupt feel that he was being superseded by his subordinate, leading him to increase his control, which generated strife with Knigge, who felt that he was being treated badly. According to Knigge’s account, Spartacus (Weishaupt’s Illuminist code name) abused and tyrannized his subordinates and intended “to subjugate mankind to a more malicious yoke than that conceived by the Jesuits.”

On July 1, 1784, the Illuminati issued an official expulsion order against Knigge. The purging of Knigge, whose organizational and recruiting abilities had brought the Illuminati to a membership of around 2,000, came at an especially bad time. One week before, on June 22, the Bavarian government had issued its first edict forbidding membership in secret societies. Other edicts would follow on March 2,1785, and on August 16. On January 2, 1785, the prince-bishop of Eichstaett demanded that the prince of Bavaria purge all Illuminati from the University of Ingolstadt. In spite of the secret membership rolls, Weishaupt was a prime suspect because of the radical Enlightenment books he had ordered for the university library. He was removed from his chair of canon law on February 11, 1784.

Over the next year, the hue and cry against secret societies increased dramatically. Ratiier than wait for his dismissal to develop into criminal prosecution or a hefty fine, Weishaupt fled from Ingolstadt to the neighboring Protestant free city of Regensburg on February 2, 1785. When the Bavarian government demanded his extradition and put out a reward for his capture, Weishaupt fled to the Protestant duchy of Gotha, where he and his family found protection under fellow Illuminatus Duke Ernst II.

If the Bavarian authorities had left it at that, the Illuminati would probably have remained a minor footnote in a very small book. But, in June 1785, certain important papers were found among the effects of Jakob Lanz, a secular priest and Illuminatus who had been struck dead by a lightning bolt. These papers testified to the Illuminati’s intention to subvert the Masonic lodges. In October 1786 and May 1787, more papers were discovered when the house of Illuminatus Franz Xaver Zwack was searched after he had been demoted from his position at the court council and sent to Landshut. These papers, which constituted an internal history of the organization, proved the conspiratorial nature of the secret society beyond a doubt. The Bavarian government made a fateful decision: They published what they had found and, thus, assured Weishaupt and his conspirators an influence they never could have achieved on their own. The first batch of documents was published on October 12, 1786, igniting a furor that would last for years.

From the time Voltaire became enamored of Newtonian physics during his visit to England in the 1720’s, Enlightenment thinkers had aspired to create a replacement for the Christian social order based on “scientific” principles. “Mankind,” wrote Baron D’Holbach in his influential treatise The System of Nature, “are unhappy, in proportion as they are deluded by imaginary systems of theology.”

As the initial Illuminist documents began to be published, Weishaupt’s revolutionary intent became clear. In his 1782 speech, “Anrede an die neuaufzunehmenden Illuminatos dirigentes,” Weishaupt provided his enemies with clear evidence that his secret society was intent on toppling throne and altar throughout Europe. Rossberg called the speech the “heart of Illuminism,” while Leopold Alois Hoffman, one of the leading lights in the counterrevolutionary movement, felt that he could trace the “entire French revolution and its most salient events” back to the maxims of the Anrede.

But the significance of Illuminism did not lie in its exhortation to topple throne and altar. Rather—and this is what the conservative readership found most disturbing—Illuminism seemed to propose an especially effective system to bring about those ends. Weishaupt had developed a system of control based on disciplined cells that would do the bidding of their revolutionary masters—often, it seemed, without the slightest inkling that they were being ordered to do so. This system was effective precisely because it repudiated the crude materialism of most well-known Enlightenment thinkers. In his treatise “Pythagoras or the consideration of a secret art of ruling both world and government,” Weishaupt proposed his system as the only possible way to implement the imperatives of the Enlightenment. “Is there any greater art,” he wrote,

than uniting independently thinking men from the four corners of the earth, from various classes, and religions with no impediment to their freedom of thought, and in spite of their various opinions and passions into one permanently united band of men, to infuse them with ardor and to make them so receptive that the greatest distances mean nothing so that they are equal in their subordination, so that the many will act as one and from their own initiative, from their own conviction, something that no external compulsion could force them to do?

Weishaupt’s system was based on the organization that was considered the antithesis of the Enlightenment: The Jesuits. As Abbe Augusin Barruel would put it in his monumental antirevolutionary Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, the Illuminati were a cross between the Jesuits and the Freemasons, in which all of the controls placed on spiritual direction by the Church were lifted and whose goal was not to get souls into heaven but to create a paradise on earth. Illuminism was a machine that stripped the esprit de corps of the Jesuit order of all its superstitious accretions and allowed that mechanism to be used to achieve Enlightenment ends. This is precisely what the conservative reaction saw in the Illuminati, and it scared them.

“Anyone who remembers the artificial machine of the former Jesuits,” wrote an indignant writer in the conservative-reactionary journal Eudaemonia in 1796, “will not find it difficult to rediscover this same machine under another name and with another motive in the Illuminati. The former Jesuits were driven by superstition, and the Illuminati of the present are driven by their unbelief, but the goal of both is the same, the order’s universal domination of all of mankind.”

It was not the goal of world domination that the public found so upsetting; it was the means whereby the Illuminati was attempting to achieve that goal. Weishaupt took the ideas of examination of conscience and sacramental confession from the Jesuits and, after purging them of their religious elements, turned them into a system of intelligence gathering in which members were trained to spy on each other and inform their superiors. Weishaupt introduced what he called the Quihus Licet notebooks, through which the adept bared his soul for the inspection of his superiors. The Quihus Licet books, Weishaupt said, were “identical to what the Jesuits call confession,” and he told Zwack that he “borrowed the idea from the Jesuit sodalities, where each month you went over your bona opera in private.”

The adept sent these monthly reports to the provincial under the title of Quibus Licet, to the provincial under the title Soli, and to the general of the entire order under the title Primo. Only the superiors and the general knew the details discussed therein, because these letters were transmitted to and fro among the minor superiors.

We can see in the Quibus Licet the vague outline of the system of spying which would become part of the communist system of control, both of the underground cells before they took over a country and as part of the police state erected after they had seized power. But the Illuminist system went deeper than that. Weishaupt created a technique that came to be called “Seelenspionage,” or “spying on the soul,” whereby the superiors in the Illuminati could gain an understanding of the adept’s soul through close analysis of seemingly random gestures, expressions, or words that betrayed the adept’s true feelings. “From the comparisons of all these characteristics,” Knigge wrote, “even those which seem the smallest and least significant, one can draw conclusions which have enormous significance for knowledge of human beings, and gradually draw out of that a reliable semiotics of the soul.”

As part of the systemization of this semiotics, Weishaupt—not unlike Alfred Kinsey 150 years later—developed a chart and a code to document the psychic histories of the various members of the Illuminist cells. In his book on the Illuminati, van Duelmen reprints the case history of Franz Xaver Zwack. In it, we see a combination of Kinsey-style sexual history, a Stasi file, and a modern credit rating. The superiors in the Illuminati could learn from its neat columns where the adept was born, his physical characteristics, his aptitudes, his friends, and his reading material, as well as his code name and when he was inducted into the order. Under the heading “Morals, character, religion, conscientiousness,” we learn that Zwack had a “soft heart” and that he was “difficult to deal with on days when he was melancholy.” Under “Principal Passions,” we read that Zwack suffered from “pride, and a craving for honors,” but that he was also “honest but choleric with a tendency to be secretive as well as speaking of his own perfection.” For those who want to know how to control Zwack, Massenhausen (code name: Ajax) says that he got the best results by couching all of his communications with Zwack in a mysterious tone.

When the Illuminist manuscripts were published, the educated public was appalled by these sinister delving into the most intimate recesses of the soul, but they were also fascinated by the opportunities for control that these discoveries opened. Wieland saw in the Illuminati the basis for pedagogical and political reform—which was, of course, the way Weishaupt saw things, too. His goal was the creation of a social order consistent with both Enlightenment science and the notion of emancipation from princes. “The truly enlightened man,” Weishaupt wrote, “has no need of a master.” Man will be well governed only when “he is no longer in need of government.”

The Enlightenment appeal to liberty invariably led to the suppression of religion, which led to the suppression of morals, which led to social chaos. Thus, those who espoused Enlightenment ideals also had to be interested in mechanisms of social control. Freedom followed by draconian control became the dialectic of all revolutions; in this regard, the sexual revolution was no exception. In fact, “revolution” and “sexual revolution” were, if not synonymous, certainly contemporaneous. Once the passions were liberated from obedience to traditional moral law as explicated by Christianity, they would have to be subjected to a more stringent form of control in order to keep society from falling apart—something the French Revolution would make obvious. The chaos stemming from the French Revolution, in fact, inspired Auguste Comte to create the “science” of sociology, which was both an ersatz religion and a way of bringing order out of chaos in a world where men no longer found the religious foundation of morals plausible.

Weishaupt’s system of control proved effective in the absence of religious sanction, and it became the model of every secular control mechanism of both the left and the right for the next 200 years. Weishaupt was wise enough to see that “reason” of the sort proposed by the Masonic lodges of strict observance would never bring about social order. As the chaos in those lodges proved, reason often led to conflicting ideas about which program to follow. The Illuminist system took the law into its own hands and molded its members’ behavior as its leaders saw fit. As in the case of Comte’s sociology, the old Church was replaced with a new one. The old order, based on nature and tradition and revelation, was replaced by a new totalitarian order based on the will of those in power. The breakup of the Illuminati and the defection of Knigge, who found the emerging order more intolerable than the one he was trying to destroy, showed that this new order was not without its problems, but faith in ever-more-effective technologies of control, based on newer technologies of communication, would push this disillusionment further and further into the future.

The Illuminati were a concrete manifestation of Francis Bacon’s dictum that knowledge is power. In this instance, knowledge of the inner life of the adept translates into power over him. Extrapolated to a state functioning according to Illuminist principles, this knowledge translated into political power. In the control of these Maschinenmenschen, both Weishaupt and Knigge caught sight of a machine-state that could create order through invisible control of its citizens.

While Weishaupt and Knigge failed to implement that vision, the publication of their papers ensured that others would at least entertain its ultimate fulfillment. Once released into the intellectual ether, the vision of machine people in a machine state controlled by Jesuit-like scientific rulers captured the imagination of generations to come, either as Utopia (in the thinking of such people as Auguste Comte) or dystopia (in, for example, the work of Aldous Huxley and Fritz Lang, whose film Metropolis seemed to be Weishaupt’s vision come to life). Like Gramsci, Weishaupt proposed a cultural revolution instead of a political one. He wanted to “surround the mighty of this earth” with a legion of men who would run his schools, churches, academies, bookstores, and governments —in short, a cadre of revoluHonaries who would influence every instance of political and social power and educate the society- to Enlightenment ideas. Van Duelmen notices the connection between the cultural revolution which Weishaupt proposed and the “march through the institutions” which the 68ers brought about less than 200 years later. The rise of communism obscured the fact that, for the first hundred years or so following the French Revolution, Illuminism was synonymous with revolution, both in theory and in practice.

Like so many who would come after him, Weishaupt sought to create a technology of control to take the place of self-control, which he lacked. At least part of the outrage which surrounded the publication of the Illuminist manuscripts arose from the disparity between the morality which Weishaupt preached and the depravity of his actions. Weishaupt had an affair with his sister- in-law; when she became pregnant, he tried to cover up his involvement by procuring an abortion. This behavior led Prince Karl Theodore of Bavaria to denounce Weishaupt as a “villain, perpetrator of incest, child murderer, seducer of the people, and leader of a conspiracy which endangered both religion and the state.” The prince was right in seeing Weishaupt as representing the antithesis of the Christian state. The essence of this antithesis was the idea of control, the desire to dominate rather than serve, which St. Augustine termed “libido dominandi.” If Christianity held loving service as its ideal, its revolutionary antithesis could only be domination. The most effective means to achieve that domination would be worked out in detail over the next 200 years. Weishaupt, however, made a significant first step by defining the terms. The battle for liberation would be both semantic and a battle for control of the soul; control would remain the essence of revolutionary practice, no matter how much the term “freedom” was used to justify its opposite.

Any objective analysis of the social engineering that has been the hallmark of American culture —from the “melting pot pageants” of World War I through Alan Dershowitz waving the bloody underwear of the sexual revolution in his defense of President Clinton —would have to conclude that Adam Weishaupt succeeded beyond his wildest dreams in creating a system of control based on the manipulation of human passion. Everything from Watson’s behaviorism to advertising to sex education to pornography on the internet is part of that system, and it is all justified by appealing to the Whig idea of freedom. The real purpose is control, but it was all the work of human hands and, therefore, of people in rooms somewhere. Those who used social engineering during this century to overthrow the political order in this country and to destabilize the moral order upon which it was based were conspirators, and the essence of their conspiracy—controlling people through the manipulation of their passions—goes back to the grand conspiracy conceived by Adam Weishaupt.

When St. Augustine wrote the City of God at the dawn of the Christian era and the end of classical antiquity, he joined the notion of freedom then regnant among the ancients with the new notion of moral probity expressed in Christianity. “A man,” he wrote, “has as many masters as he has vices.” For roughly 1,300 years, that sentence was taken as a warning. In the context of the Enlightenment, however, it could also be seen as a recipe for political control, which is precisely how it was implemented. St. Augustine delineated the two options: the City of God, which is based on love of God to the extinction of self; and the City of Man, which is based on love of self even to the point of desiring the extinction of God. If the City of God is based on love and service, the City of Man is based on their opposite, namely, libido dominandi, the desire to dominate one’s fellow man for personal benefit. Once the Enlightenment decreed war on Christianity, the program of libido dominandi became inevitable. No one has to conspire to get people to act on their baser passions, but that does not change the fact that a conspiracy did form to bring about that end. It is with us still.

Most people know this intuitively, even though — left to their own devices—they will come up with a cockamamie theory of the sort proposed by Veronica Leuken, the phony “seer” of the phony Bayside, New York, apparition, who informed the credulous that all of the disconcerting changes in the Catholic Church over the past 3 5 years were traceable to the fact that the real Pope Paul VI had been kidnapped and an impostor (look at his ears) had been placed on the Chair of Peter. While Veronica Leuken’s explanation of everything may be wacko, it is not as wacko as the anti-conspiracy theories of people such as the professor from Cincinnati. It reminds me a bit of the man who, when he had evolution explained to him, opined that it was easier to believe in God. When it comes to history, it is easier to believe that it was people in a room somewhere.

Leave a Reply