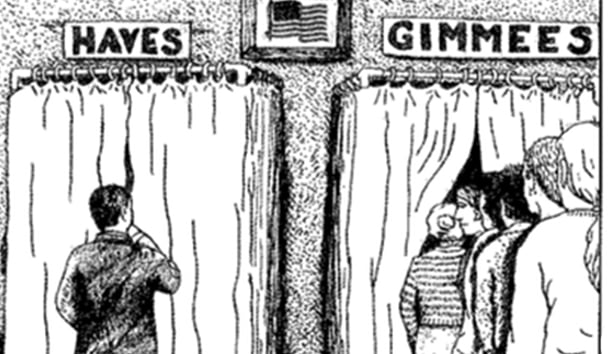

The interplay of race and economics in America has produced a new variant of political economy that we might call “multicultural capitalism,” a system in which property is, for the most part, privately owned, but its ownership is conditional on the race, sex, and—in some cases—the sexual orientation of the owner. In the pursuit of the chimera of racial and sexual “equality,” the old system that regarded private property as an inviolable right has been replaced by one in which certain classes are granted power by the state to override property rights and, in effect, to appropriate private property for themselves. “Oppressed minorities” in America are accorded all sorts of “rights” not enjoyed by ordinary folk. Affirmative action in education and employment, special protections via “hate crimes” legislation, the sympathetic attention of political and cultural elites: These are just the most luxuriously obvious perks of oppression, but they are merely fringe benefits for the aristocrats of the new victimological order. The foundation of their power is a virtual stranglehold over all economic activity under our civil rights laws.

The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act marked the beginning of the end of private property in America. As one of the few senators who voted against it, Barry Goldwater, remarked during the debate on the bill: “I am unalterably opposed to discrimination of any sort, and I believe that though the problem is fundamentally one of the heart, some law can help, but not law that embodies features like these, provisions which fly in the face of the Constitution, and which require for their effective execution the creation of a police state.”

Those words have a prophetic ring to them, especially in light of the victimological assault on the Denny’s chain of restaurants. Beginning in 1993, Denny’s management came under a concerted and relentless attack by private interest groups in league with the federal government, which initiated a series of lawsuits that eventually brought the company to its knees. In San Jose, California, several black teenagers were refused service unless they agreed to pay in advance. The next year, six Asian-Americans at Syracuse University visited a Denny’s and claimed that they had to wait over 50 minutes for service, unlike white patrons. The Asian-Americans complained, leading to a ruckus in the restaurant, which eventually spilled out into the street. These incidents spawned lawsuits, which Denny’s eventually settled, but that was not the end of it. On April Fool’s Day, 1993 (the same day that the first suit was put to rest), six black Secret Service agents walked into a Denny’s in Annapolis, Maryland, and claimed to have been subjected to blatant discrimination: The problem, it seems, was that they had to wait an hour for their orders to arrive. According to an account in the Washington Post, the delay was so prolonged that they were “in effect denied service”—on account of their race, of course. The Post cited Robin D. Thompson, one of the black agents, as claiming he “felt humiliated” by the incident.

What happened that day in Annapolis, when 21 Secret Service agents were en route to an appearance by President Clinton at the Naval Academy, is indicative of what Goldwater meant when he predicted that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 could not be enforced without establishing a police state. Every small action counted as evidence in this ease. The black supervisor and a group of white agents sat together, while the six black agents sat at a separate table. The supervisor and the white guys were served, while the black agents looked on. They summoned a waitress to the table; she assured them that their food was on the way. The Post reported with a straight face that “White agents have told the Washington Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, which is handling the agents’ lawsuit, that the waitress rolled her eyes after turning to leave the black agents’ table.”

So this is the real use of our “civil rights” laws, supposedly charged with protecting the rights of the “oppressed”: as a bludgeon against a lowly waitress, who dared protest her humiliation at the hands of rude customers.

Denny’s management denied the claims of the complainants. Steve McManus, senior vice president of Flagstar, Denny’s parent company, pointed out that the large size of the party was the key factor in the delay. The black agents, it turned out, had taken their time ordering. “It’s a service issue, not a discriminatory issue,” McManus said. But in the surreal world of our civil-rights laws, there is no way to tell the difference. As Goldwater put it, this is “a matter of the heart,” and there is no way to prove “discrimination” on any basis except by looking directly into someone’s heart—and that is not possible. Under current law, however, it is the option of judges and juries, as well as government bureaucrats, and that is how we came to the nightmarish end of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream—in which the facial expression of a waitress is used as “evidence” of “discrimination.” The subjectivity of this whole area of law is apparent: A delay in getting an order of hamburgers and fries is thought, by the black agents, to be “a classic case of bias,” as agent Thompson put it—or, from the waitress’s viewpoint, a classic case of b.s. It is all a matter of perception, not fact, and therein lies the danger. Unless judges and juries are mind readers, the behavior of an eye-rolling waitress must remain a mystery about which we can only speculate: Was she a dyed-in-the-wool racist, or had it been a long day, full of abusive customers who had subjected her to more than the usual dose of humiliation visited on service employees? The lawyers and judges of today pretend they can know, and so does the Justice Department, which thundered that the settlement reached in the previous case was only tentative and demanded an explanation from Denny’s management. The class-action lawsuit filed by the six Secret Service agents was joined by thousands all across the nation, becoming the largest case in the history of public-accommodations law.

The first impulse of Denny’s management was to fight back. Flagstar CEO Jerry Richardson defined the central issue when he asked, “If our African-American guests were mistreated, was it because of racism? I can’t tell you. It’s impossible to know what’s in a person’s heart.” But pressure began to build as the victimology brigade took up the cry of “racism!” and the costs of fighting the battle mounted. Flagstar tried appeasement: In 1993, the company signed an agreement with the NAACP pledging to hire more minorities, patronize minority-owned suppliers, and set up a jointly operated customer complaint department. But this only whetted the appetite of the shakedown artists, who preferred cash to goodwill gestures. The key issue, according to the NAACP, was redress for past discrimination on the part of Denny’s. At this point, with the whole weight of the Justice Department bearing down on it, pickets outside its restaurants, and editorialists hurling anathemas, Flagstar raised the white flag. As of December 1995, Denny’s had been shaken down for $54 million paid out to some 295,000 plaintiffs and their lawyers. Why did Flagstar surrender? “I had to consider the cost of the litigation,” explained Richardson, “which would have been astronomical even if we’d won every trial.” And then there was the public-relations aspect of a prolonged trial: “Litigating was going to take years,” Richardson said, “and you can’t go for years being at war with a percentage of your customers.” Exhausted by the relentless assault of the professional victimologists and their governmental co-conspirators, Flagstar got taken to the cleaners. It could have happened to any company in America.

The Denny’s saga was only the most memorable in a long series of recent court cases in which the charge of “racism” is enough to doom a company to years of litigation and demonization in the liberal media, which is all too eager to provide a platform for any complaint of “discrimination.” It is almost worse than useless to fight such cases: Given the cultural and political atmosphere, a legal “victory” can, in the long run, wind up costing a company more than a defeat.

Socialism is widely thought to have been defeated, both intellectually and politically, while a wave of free-market libertarianism is supposedly sweeping the globe. But if we look at the effectiveness of the civil-rights revolution in the economic realm, we can see that the followers of Martin Luther King, Jr., succeeded where Lenin’s heirs failed. The 1964 Civil Rights Act, which forbade “discrimination” in housing, employment, and public accommodations, sounded the death knell of property rights in America and inaugurated the police state foreseen by Goldwater—an Orwellian enforcement apparatus geared toward the extension of the “discrimination” concept to encompass the importunate rolling of a eye.

“Non-discrimination” inevitably grew to mean minority preferences—i.e., affirmative action—since there is no way to measure a completely subjective concept such as “discrimination” except by running the numbers. Since we cannot read the mind of the accused and can only infer his motives, the only measure of a white employer’s racial mindset comes from counting his black employees. Do the numbers reflect the demographics of the area in which the business is located? If not, then—obviously—”discrimination” is at work. Such is the Jacobin logic of civil-rights legislation, which enforces homogeneity in the name of diversity and elevates a whole class of human beings on the basis of their skin color—in the name of racial “equality.” In effect, civil-rights legislation, if consistently enforced, must mean quotas, whether openly acknowledged or managed more discreetly.

W/lien William F. Buckley, Jr., declaimed that it was time to concede on the issue of civil-rights laws, he said that he was unwilling to go to the barricades to defend the right of Lester Maddox not to serve a plate of pork chops to a Negro. But what about the rest of us, abandoned to the depredations of race-baiters and crusading victimologists? It was incredibly naive of Mr. Buckley and his colleagues at National Review to have imagined that the whole process would end with forcing the Lester Maddoxes of this world to mind their manners. In any case, this occurred, ultimately, not by force of law but because of the laws of the market.

Everyone wanted to cash in on a very lucrative racket, and the concept of “discrimination” was gradually extended to areas beyond race, religion, and sex. It was inevitable that the aspiring gay-rights movement would latch onto the rhetoric first popularized by Martin Luther King, Jr., and the black civil-rights movement. For opposing this extension of the civil-rights principle, conservatives are smeared as bigots, just as Goldwater was for voting “nay” on the first federal Civil Rights Act. Goldwater stood on principle, but today’s conservatives do not have a leg to stand on: Having long ago conceded the validity of the “anti-discrimination” principle, they are helpless to limit its application—especially as social trends go against them.

The official establishment-conservative line is that the civil rights movement was a good thing gone bad. Back in the old days, when St. Martin walked the earth, the civil-rights movement was supposedly a fight against state power. It was only later, after it was corrupted by the poverty pimps —the Jesse Jacksons, Al Sharptons, and other race-hustlers in league with urban Democratic party bosses—that the movement took the wrong road. This is unmitigated hogwash. The movement led by King and other more radical figures was the rallying point for the left in the 1960’s precisely because it implied the overthrow of capitalism by elevating “civil rights” above property rights. It was only natural for the concept to be extended continually until it now seems almost infinitely elastic. The latest development is that the gay lobby, having long ago won the battle to secure its “civil rights” in the state of California, is now seeking to emulate San Francisco and other “progressive” cities by outlawing discrimination against “transsexuals”—castrati who, through the miracle of plastic surgery and regular hormone treatments, have managed to convince themselves and a growing number of legislators that they have made the transition from male to female. In San Francisco, these self-mutilated creatures are accorded all the “civil rights” granted to officially state-sanctioned victim groups—protection from “discrimination” in housing, employment, and public accommodations—and there is a move afoot to enact a similar law on the state level. Back in the 1970’s, San Francisco passed its own comprehensive gay-rights legislation; then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s doubts were overcome by gay lobbyists who assured her that it would not mean that companies would have to hire men who came to a job interview in drag. Today, it means precisely that, and the city’s Civil Rights Commission is fully empowered to initiate legal action against the offending “homophobe.” we are near the bottom of the slippery slope; is there any way to avoid falling into the pit?

If we are looking to what passes for the conservative movement for any leadership on this issue, we are bound to be disappointed. When I made this argument during a panel on the gay-rights question at National Review‘s 1993 “Conservative Summit,” I ran into the voluble opposition of my fellow panelist, David Horowitz, head of the Center for Popular Culture and a well-known neoconservative. Horowitz was outraged by my reference to “St. Martin Luther King” and the suggestion that, instead of praising this secular saint, we ought to be calling the whole civil-rights paradigm into question. “I can’t let pass the remarks of Justin Raimondo, which were appalling to me, without a comment here,” he thundered. “This country committed a great crime, not only against black people but against itself, in the institution of slavery, which is fully justified by the property rights that Justin Raimondo thinks will cover everything.” Horowitz attacked as “garbage” the idea that “there’s no difference between [King] and Louis Farrakhan or the contemporary radicals who have hijacked the civil rights and turned it for their radical agenda.”

This is a typical argument from far-out leftists: The fact of slavery entails some kind of debt on those who had nothing to do with it. This, I thought at the time, was an odd appeal to make to conservatives—invoking the concept of collective guilt, similar to that visited on Germans born long after Hitler and the Third Reich went down in flames. The idea that King was a self-conscious radical who was surrounded by close advisors with links to radical organizations is acknowledged by his most sympathetic biographers. But Horowitz’s guilt-tripping did not end there; he was just getting warmed up. He launched into a long tirade about how he thought it was a “disgrace” that “I go from conservative meeting to conservative meeting and see two or three black people in the audience and maybe a couple of Hispanics.” It is all because of Pat Buchanan—his voice had by this time reached such a high pitch of righteous anger that it threatened to crack—and, if the GOP goes Buchanan’s way, “then there’s no future at all for the conservative movement in the Republican party.”

The GOP, of course, did not go Buchanan’s way, and there is still no future for the conservative movement in the Republican party. But, setting that aside, how will conservatives prevent the redistribution of wealth in the name of race, sex, and all around “equality” if their alleged leaders insist we all worship at the altar of MLK? As long as conservatives pander to the political correctness that animates their worst enemies, the politics and culture of this country will inevitably be dragged to the left. (Someday soon, a “centrist” will be someone who wants to forge a legislative compromise on the issue of “transsexual rights.”)

The civil-rights revolution effected a sea change not only in the realm of law but in the political culture; unless that change is reversed or ameliorated, the displacement of property rights by civil rights will become permanent and all-encompassing. Instead of talking about “empowering” minorities, the men and women of the right must challenge and roll back the advances that egalitarian ideology has made in their own ranks. Yes, Barry Goldwater was right about the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and conservatives desperately need to rediscover and reclaim the libertarian spirit that animated his principled dissent. The state cannot legislate the preferences and prejudices of its subjects without ultimately establishing a dictatorship. The right office association, the right to enter into contracts, and the right to control and dispose of one’s own private property—the very basis of all rights—are bedrock principles that must be defended by y conservative movement worthy of the name. If this be bigotry—and it is not, at least not in a sane world—then so be it. Under these circumstances, it is far better to be a “bigoted” freeman than a tolerant slave.

Leave a Reply