“Jesus was an asylum seeker,” according to the website of the Baptist Union of Great Britain. “He would have known from his parents just what they had to go through in their search for sanctuary,” the site declares. “He would have been—and is today—angry at the way they and many others are treated in a system that neither welcomes nor wants the stranger in its midst.”

“The Jesus we follow was a refugee and an immigrant,” we are told by a priestess of the United Church of Christ and a member of its Immigration and Refugee Task Team. “This Advent… when we see the pictures of drowned refugee children on beaches… and babies carried in their parents’ arms across borders, we remember that these too are the face of Jesus.”

“In this season of waiting and hoping, displacement is at the heart of the Advent story,” according to Global Refuge, formerly known as Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. “The Holy Family was famously not invited into anyone’s home, despite their vulnerable state. They needed shelter for a safe birth of Jesus, but ‘there was no room for them in the inn.’”

Through its 24-day Advent calendar, Global Refuge says, “we invite you to experience stories of immigrants … while reflecting on the Holy Family’s experience of displacement during that first Christmas.” Presumably such reflection will help you accept Global Refuge’s core belief “that we are called to welcome those fleeing persecution and seeking refuge in the United States.”

So, Jesus and the Holy Family were vulnerable, displaced and homeless refugees, persecuted asylum seekers, vulnerable persons, or perhaps immigrants. Nice and touching, and repeated ad nauseam by the legions of bien-pensants and progressive clergypersons all over the Western world. And wrong.

First, it is absurd to use contemporary terms which imply modern meanings of statehood, displacement, and citizenship in the context of the Middle East of 2,000 years ago. Worse still, people with a political agenda—pro-immigration activists, Sorosite population-replacement operatives, open-borders enthusiasts—are mendaciously manipulating those terms to serve their agenda to suggest that “Jesus was an immigrant, therefore immigration is good,” or that “the Holy Family were asylum seekers, therefore we should welcome asylum seekers.”

When Christ was born, Joseph and Mary were not “escaping persecution.” They were traveling, indeed, but the purpose of the journey was perfectly mundane: to fulfill their civic obligation and register for the census of Quirinius. They had to travel some 90 miles from Nazareth to Bethlehem because “everyone went to their own town to register” (Luke 2:3). Bethlehem was the town of David, and Joseph was of the line of David.

Contrary to the Global Refuge implication, the “inn” did not maliciously deny accommodation to “aliens,” and the innkeeper was not a callous xenophobe. He did provide the couple with the kind of accommodation, which—back then, and for many centuries before and after—was commonly made available to travelers when there were no vacancies in the main building: in the barn.

There is no evidence that Mary gave birth the night they arrived and therefore needed shelter urgently. The Bible simply says that, “While they were there, the time came for the baby to be born” (Luke 2:6). In any event, the Bible does not claim that Jesus was born in a stable; it simply says that Mary “wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no guest room available for them” (Luke 2:7).

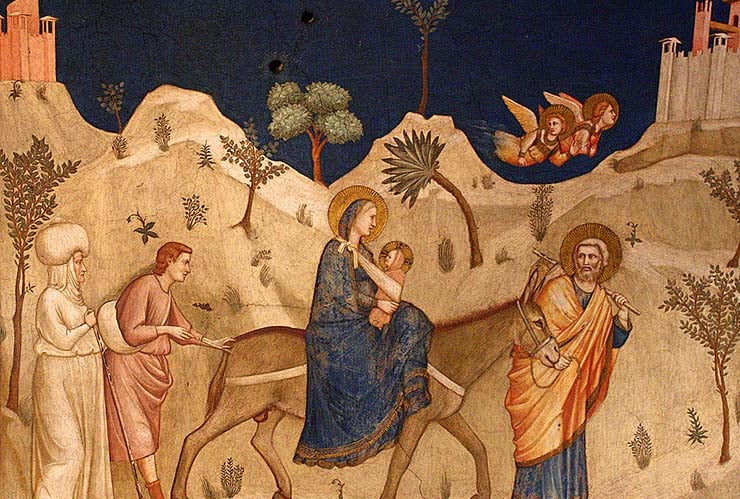

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “immigrant” as a person who comes to live permanently in a foreign country. Mary and Joseph and their child moved temporarily to Egypt, in response to the alarming stories of Herod’s massacre of the children. Herod was a client king who enjoyed limited autonomy within the Roman Empire. As it happens, Egypt also was a province of the Roman Empire. In today’s parlance and UN classification, therefore, they were Internally Displaced Persons rather than “refugees.”

When the danger was over, Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus returned home to Galilee. It was ruled by Herod the Great’s son Herod Antipas, and it was also situated within the Roman Empire. Joseph and his family moved around like one would between states, rather than countries, and certainly not in some kind of desperate quest for sanctuary.

For the Holy Family to be asylum seekers or immigrants, they would have needed to move some hundreds of miles east, to the Parthian Empire, which was centered on today’s Iran. To be like 99.9 percent of today’s asylum seekers, they would have needed to intend to stay in the Parthian Empire forever, regardless of whether it was safe to return home or not. And again, to be like today’s asylum seekers, in their new abode they should have received financial support, material benefits, tons of counselling from full-time staff, as well as free accommodation and healthcare—all that at public expense

By contrast, when the real and present danger was over, Joseph and his wife and child duly left Egypt and returned home where he put bread on the table by working as a carpenter.

Neither the Old nor the New Testament talk about a person becoming a member and permanent resident of another country or society. In the Hebrew Bible there is not the slightest hint of allowing for assimilation of non-Jews, let alone “loving” strangers. For the Jews to welcome a Samaritan refugee in their midst would have been a tall order indeed.

In the early years of the Christian era, we may have had missionaries going to other nations to preach the Gospel, but they would have done so on the equivalent of today’s temporary work visas. On the other hand, the Gospel clearly orders Christians to respect the laws. If that means anything in this context, it means that they should oppose illegal immigration.

Leave a Reply