With tensions rising between nations such as Taiwan and China, as well as between Russia and Ukraine, many are wondering how involved the Biden administration will be. Should the United States leave these nations alone, or should they interfere? A look at the past through Stephen Wertheim’s new book, Tomorrow, the World: The Birth of U.S. Global Supremacy, may shed some light on that question.

Tomorrow the World explores the development of the U.S. before and during the Second World War as a global power committed to a global moral mission. America’s liberal internationalist foreign policy, now most closely identified with neoliberals and neoconservatives, was not always popular among American political leaders, explains the author, who is the Deputy Director of Research and Policy at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. A less ambitious foreign policy prevailed in the 1920s and 1930s because of widespread regret over American involvement in World War I. American political leaders, who had been profoundly disillusioned by American participation in that struggle and the unjust treaty that ended it, prescribed extreme caution in dealing with foreign conflicts. Thus, the American government was urged to think twice before becoming embroiled militarily again.

This approach, Wertheim, points out, was not “isolationism,” which is a term that liberal internationalists throw at their opponents. Instead, critics of the internationalist perspective insisted on limiting military engagements to those which protected American citizens. These critics also recoiled from the kind of moralizing that accompanied American military participation as a quasi-religious act. A different course was chosen, however, and Wertheim’s book is an attempt to explain why that decision was made, as well as the events leading up to that fateful choice.

The author recognizes that liberal internationalists, who viewed themselves as following in the footsteps of their hero Woodrow Wilson, still enjoyed a powerful institutional presence in the 1920s and 1930s. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was one of these ardent Wilson supporters, helping found The Woodrow Wilson Foundation which, along with the Council of Foreign Relations, was founded after World War I and worked tirelessly through educational outreach to keep the vision of an Anglo-American alliance for policing the world alive and well.

Yet the disenchantment with World War I remained strong, aided by the memory of over 100,000 American deaths in what had been a war between European cousins. In the 1930s conservatives and progressives in both national parties became opponents of American military involvement, although both furnished enthusiastic interventionists during World War I.

The rise of a belligerent Nazi Germany and the challenge to American military power posed by the Japanese empire in the Pacific caused American elites to abandon this restrained view of America’s place in the world. Instead, the idea that no permanent peace was possible until a world body under American leadership was formed to shape and guarantee a global order took hold.

The League of Nations resulting from World War I had been unable to provide collective security. It was widely criticized for its failure to prevent both Nazi Germany’s takeover of Eastern Europe and the Japanese occupation of Southeastern Asia before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Moreover, the refusal of the American Senate to approve American membership in this body was rightly or wrongly seen as a key reason that the League failed.

It was therefore the U.S.’s duty to lead the way toward international cooperation against future troublemakers. The American government claimed to be doing just that by laying the groundwork for the UN meeting at Dumbarton Oaks in Georgetown from August into October of 1944. In this new international body, the world’s leading powers—the U.S., the Soviet Union, China, England, and France—would hold permanent seats on a Security Council designed to collectively address conflicts wherever they broke out. This international body was also eventually equipped with a peacekeeping force that it was hoped would deescalate strife by maintaining cease-fires.

This plan seemed to be something constructive that even political leaders like Robert A. Taft, who had long warned of foreign entanglements, felt they could accept. An international organization that would allow conflicts to be resolved without dragging the U.S. into further wars gained approval even among some “isolationists.”

Unfortunately, according to Wertheim, this plan quickly went awry because the Security Council was beset by conflicts among the great powers, not all of which were equally powerful. The Council and the UN were split by the Cold War, as well as struggles among newly independent colonies in Africa and Asia. Later it was thought that both internationalism and international campaigns for human rights were worth pursuing, but the UN was not up to this task.

By the 1970s a new liberal internationalism arose that was particularly attractive to neoconservatives. Although the U.S. and its “democratic” allies were correct to pursue a neo-Wilsonian foreign policy, they had to do so mostly outside the UN, it was argued. Only like-minded countries working together under American or Anglo-American leadership would be part of the effort to promote this moral foreign policy.

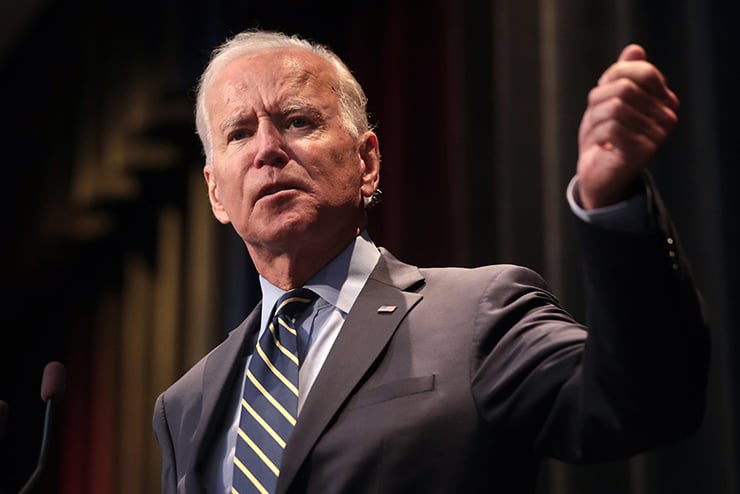

Wertheim has no use for any variation of liberal internationalism, but it is never clear what exactly he is proposing as a workable alternative. His recent turn toward the Biden presidency for a foreign policy solution seems driven by partisan loyalty. While Wertheim approves of Biden’s China-friendly policy, he fails to distinguish between possible fence-mending and the shameful record of accepting Chinese bribe money that is attached to Biden, his son, and his brother. There is a useful distinction to be drawn between a diplomat and an asset. (Biden unfortunately may be the latter.)

Biden and his party have also needlessly gone after Russian President Vladimir Putin and the Russian government for being linked to the Trump administration in ways that have never been proven. How exactly does the Biden team plan to relieve the same tensions with Russia that they have exacerbated while engaging in domestic partisan battles?

Wertheim may do better exposing a defective foreign policy than offering alternatives. It is also an open question whether a realistic or dispassionate approach to foreign policy is even possible in our current ideological culture.

Image Credit:

Flickr-Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0

Leave a Reply