H.M. Maisky was the Soviet ambassador to Britain from 1932 to 1943. In June 1943 Stalin ordered him to quit London. After returning to Moscow, Maisky was posted henceforth to unimportant positions. In 1953 he was imprisoned; two years later he was released. He died in 1955.

In London (and from time to time in Moscow) Maisky kept a diary, excerpts from which were published in 1967. A much larger portion has now been published by Professor Gorodetsky of All Souls College, Oxford, an expert in the history of that period who furnishes extensive explanations and annotations of the text. Historians in England and in America have gone to extremes in praising this volume. “Astonishing! Really remarkable . . . Perhaps the greatest political diary of the twentieth century” (Paul Kennedy, Yale). “Of major historical importance” (Anthony Beevor). “Light from a fresh angle . . . an extraordinary document left by an extraordinary man.” Etc., etc.

I cannot agree. During Maisky’s entire career (and throughout most of his life) Stalin ruled Russia. Maisky’s influence on Stalin’s decisions was nil. When Maisky was appointed ambassador to Britain in 1932, Stalin’s concern with foreign affairs was very limited, and his interests in his ambassadors almost nonexistent. Maxim Litvinov, his foreign minister, had a view of the world that was similar to Maisky’s. The backgrounds of the two men were similar also: In 1917 they had both been Mensheviks—not yet Bolsheviks. In March 1939 Stalin cast off the Jewish Litvinov and opted for a sort of alliance with Hitler’s Germany. Like millions of people Maisky, in London, was stunned and shocked by these events, but said not a word about them. A year later, he felt more encouraged. The new prime minister of Britain was Winston Churchill, whom Maisky had begun to respect. Churchill committed his country to fight Hitler to the end, with whatever allies joined the side of Britain. Thereafter Maisky’s reputation in London rose, especially after June 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. On the night of June 22, Churchill declared to the world that Britain and Russia now were allies. In England Maisky’s prestige among all kinds of people soared. When, in June 1943, Stalin was winning his war, he discarded Maisky (and soon thereafter Litvinov in Washington, too).

The worth of Maisky’s diary consists solely in what he wrote about his relations and conversations with British leaders from 1941 to 1943. He (as also Litvinov) was an enthusiastic advocate of a British (and American) alignment and alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. The material evidence in Maisky’s diary makes it clear that Britain could not win a war against Germany, except in alliance with both Russia and the United States. Churchill knew this only too well. In July 1942 he admitted to Maisky, “The Germans wage war better than we do.” Even after the first substantial British victory at El Alamein in November 1942, he saw—and said—that this was not the beginning of the end but the end of the beginning. Maisky was also aware of Roosevelt’s more than occasional distrust of Churchill.

There are remarkable snippets in Maisky’s diaries about how and how often British political leaders of various opinions thought that, without Russia, Britain could not win her war against Hitler. Of course, an ambassador most often would be even more of an observer than a representative. But here too Maisky’s talents were limited. Throughout his career in London, he complained of the political influence of the British upper classes. At the same time he cultivated his friendships with H.G. Wells (whom he quotes as saying “What a giant Lenin was!”), Bernard Shaw, the Webbs, and the aged Lloyd George, none of whom themselves were much listened to. Maisky still believed in a world divided between capitalism and communism. Also, here and there in his diaries, we may glimpse hints of the age-old Russian inferiority complex. On August 26, 1941 (the date is significant), he wrote, “Britain and the USA imagine themselves lords and masters, judging the rest of the sinful world, including the USSR. You can’t forge friendship on such a basis.”

And his subservience to Stalin was abject. Here is a typical entry in Maisky’s diary regarding Stalin:

9 March 1943: The rank of the Marshal of the Soviet Union was conferred on Stalin. Excellent. He fully deserves this, the highest military honour—more than anybody else, not just in our time, but throughout the long history of our country.

Ten years later, Maisky (who Stalin’s closest minion, Molotov, once suggested was an English spy) was arrested, and only two weeks before Stalin died.

His present editor, Gorodetsky, is fully aware of Maisky’s weaknesses: “Always torn between fear and conceit,” he notes on one occasion. Does all of this really suggest “an extraordinary man”?”

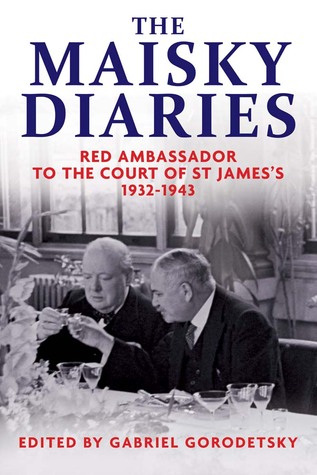

[The Maisky Diaries, by Ivan Maisky, Edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press) 584 pp., $40.00]

[Slideshow image credit: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website–www.dfat.gov.au [CC BY 3.0 au], via Wikimedia Commons]

Leave a Reply