When my daughter, Katie, was in the fifth grade, her grammar school conducted a week-long series of tests inspired by the White House to promote physical fitness for schoolchildren. Children who completed the tests with passing marks—the standards for passing were not high—received a certificate from the President. The kids ran, jumped, and stretched, and performed sit-ups and pull-ups. Katie finished second overall—not second among all the girls in the school but second among all the girls and the boys. She finished first in pull-ups, doing 14 with perfect form and beating the runner-up, a boy, by four. I was happy with her performance but flabbergasted as well. How could a girl, even if she was a McGrath, beat all the boys in the school in pull-ups and all the boys, save one, overall?

Now I must confess that Katie was no stranger to pull-ups. She not only had taken a gymnastics class for several years but had worked on a high bar in our garage. At home, under ideal conditions and with her hands properly chalked, she had done 16 strict pull-ups—not bad for a grammar-school girl. Twenty pull-ups in the Marine Corps earns a Marine maximum points on the physical-fitness test. Nor was Katie a stranger to running. She had been a high-scoring forward on various soccer teams since she was five years old. She was a natural athlete and she was well trained. But she was a girl! I asked how the boys reacted to getting beaten by a girl. She said that most of them, with a few exceptions—most notably a freckle-faced strawberry blond named Ryan who had a temper that matched his complexion—simply accepted the fact. She then asked, “How would you feel, Dad, if I had beaten you when you were in grammar school?”

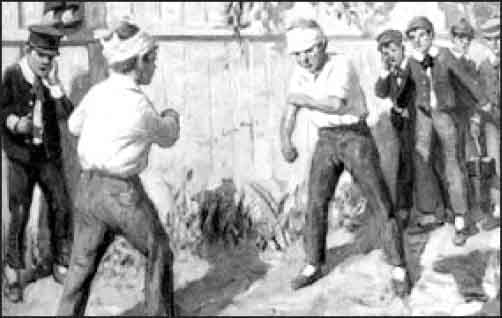

It was simply inconceivable, I told her. When another boy beat me at anything, I could not sleep, eat, or breathe until I got a chance for a rematch. A girl? No—this was unfathomable. And most boys were versions of me. We competed viciously. There was no such thing as friendly competition. If we could have killed our opponents, we would have been overjoyed. This went for kick ball, sock ball, two-square, dodge ball, softball—whatever game was in progress on the playground at the moment. A disputed call usually meant a fight, and no kid tried to break it up. Quite the opposite. It was one of the great moments of the day and only stopped when a teacher spied the commotion and raced across the blacktop to the scene. By then, the fighters were usually near exhaustion anyway. We talked about the fight the rest of the day and relished the battle while staring at the clock in the classroom. If you were in the fight and acquitted yourself admirably, you were a hero.

We competed at everything. Walking home turned into a sprint to the big oak tree on the corner or a series of standing broad jumps or one-legged hops—any and everything that could pit boys against one another. I delivered newspapers on my bicycle in the afternoon. At least once a week, after folding our papers and arranging them in our canvas bags, all of us paperboys at our “corner” would race off to see who could complete his route and be back at the corner first. On the next corner were paperboys who delivered a competing afternoon newspaper—television had not yet destroyed the printed word. We would sweep down on their corner in a surprise bicycle-propelled attack and hurl water bombs or ride through their stacks of folded papers, shredding them with our bicycle chains. They would do the same to us. Fights erupted. For some reason, our corner regularly got the better of our rivals, so much so that their paper boss, Vern, came by early one day and shoved us around.

We told our paper boss, Royal Harvey, about it. His regular schedule meant that he would arrive at our corner well after Vern had made his deliveries. Royal told us he would change his schedule for a special appearance come tomorrow afternoon. The next day, we were there early, eagerly awaiting the anticipated confrontation. The other paper boss was quite a bit taller and heavier than Royal, but Royal was one hard character. He was from Grass Valley—an old mining town in the Sierra foothills—and wore blue jeans, T-shirts, and cowboy boots. He was lean and muscular, with bulging biceps that came from working out while doing time in prison. His taut skin stretched across an angular, leathery face that suggested no softness. He looked like a cross between Johnny Cash and Bob Mitchum. He was also tough as nails. I watched early on a Sunday morning when a paper-tying machine malfunctioned and sent a wire, the thickness of a coat hanger, through Royal’s hand. Gritting his teeth and grunting, he pulled the wire back through his hand and simply tied a handkerchief around the wound and kept going. Royal was our paper boss, and we could not have been more proud.

As promised, Royal arrived early. We could hardly contain ourselves. I remember feeling as if I were about to burst. Crowding around Royal, we marched to our rivals’ corner. Vern was busy stacking and counting papers for his boys when one of them called attention to our approach. The man who had been such a tough character while shoving us paperboys around the day before suddenly looked like he very much regretted his earlier actions. Before Vern could say much, Royal threw a combination of punches that knocked the rival paper boss against a concrete-block wall. Out on his feet, Vern began to slide to the ground, as Royal grabbed him by the neck and said, slowly and distinctly, “If you ever touch one of my boys again, I’ll kill you.” Vern knew Royal meant it. Vern’s paperboys knew Royal meant it. We knew Royal meant it. We were stoked.

Royal was one of our mentors. We could not have been luckier. One of the duties of paperboys was to solicit for new subscriptions—“starts,” as we called them. We got paid a dollar for a start—good money for a kid in the 50’s. If a start was in your route’s area, then you had another delivery and an additional 50 cents per month. In the evenings, we would go from house to house, like trick-or-treaters, and pitch our afternoon newspaper, the Mirror News, and our morning newspaper, the Los Angeles Times. We would occasionally see signs next to the front doors: NO SOLICITORS! Royal told us to ignore them. The signs were for adult solicitors, he said. Just smile and tell them about the newspaper.

Since we all loved explosions, Royal gave us a bonus in cherry bombs if we got over a certain number of starts in a month. Money was certainly an incentive, but the carrot of cherry bombs inspired us to solicit with a vengeance. Although it was 40 years too early for the phenomenon of gated communities, there was a prominent exception—the Malibu Colony. It was impossible for any solicitors to get past the gate guard; the Colony was virgin territory for starts. The possibilities inside the Colony were dazzling—if only we could gain access. One night, Royal told us he had a surprise for us. He drove us up the coast highway to the Colony and parked well away from the gate. Warning us to maintain silence, he led us to the high, ivy-covered, heavy chain-link fence that provided part of the barrier for the Colony. He pulled back some of the ivy and then a small section of the fence that had been cut and exclaimed, “Look what I found!” We crawled through and had our best night of soliciting ever. No one gave much thought to the bolt cutters that Royal had sitting among his tools.

I used to try to “porch” as many papers as possible. Customers loved to see their paper sitting on their welcome mat or resting against their front doors. Tips could be good, 25 cents or more per month. I quickly came to understand trajectory. I was able to hurl a paper well before my intended doorstep while riding at full speed and watch the paper whirl through the air like a chopper blade across another house’s lawn and driveway before it came to rest on my target. I got so I could do this forehand or backhand depending on the side of the street a subscriber’s house was on. We paperboys competed in throws, too. The guys had different styles of throwing as well as different ways of folding the papers for flight. Folding configurations were hotly debated. In addition to everything else, we were primitive aeronautical engineers.

My enthusiasm for porching customers’ papers resulted in some spectacular crashes on my bike and a few serious injuries. Others suffered likewise. We took all the cuts, scrapes, bruises, and broken bones in stride. Today, there would be lawsuits. Because of its distance from the street, one house in particular gave me fits when trying for a doorstep landing. One day, when the wind was right, providing just enough lift, I let loose with a throw that sent the paper whirling through the air like a boomerang. “I’m finally going to porch it,” I thought. A few seconds later, I saw the paper not only reach the porch but hit a screen door and rip through it. I could hear the tearing sound all the way from the street. “Oh, sh-t!” I silently exclaimed. I swung my bike around and pedaled up to the house. My customer was not only home but had been sitting in the living room when the paper tore through the screen. He told me that the paper had continued on its journey, sliding down the front hallway and into the living room before coming to a rest. He also told me that this was just a bit more service than he needed. I said that I would cover the costs for the repair, while thinking that those costs would probably amount to a month’s pay.

I was one dejected kid. A month’s pay! Paperboys for the Mirror News not only delivered the paper six afternoons per week but also had to “collect” at the end of the month. Collecting was an enormous hassle. Some customers were always home and had the cash ready for me. Others seemed never to be home. I had one customer, a contractor, who would hand me a hundred-dollar bill (something like $500 today), knowing that I could not possibly make change. The next time I would show up, his wife would tell me that her husband handled all the money and that he was away on a job. Sometimes, despite my best efforts, a few customers fell several months in arrears. On the other hand, like every other paperboy, I had to have the paper there every day, come rain or high water. I delivered my papers with a cast on my arm, with a broken jaw wired shut, with fevers, with the flu. If we did not deliver, we did not get paid.

Royal lived only a couple houses away from the customer whose screen lay shredded. He heard about my Mickey Mantle shot later the same day and, the next morning, without telling me, installed a new screen—on his own time and with his own money. Royal was our guy.

Afternoon daily newspapers and paperboys are mostly a thing of the past. Even if television news had not destroyed the market for an afternoon paper, liability lawsuits would probably have destroyed the delivery job for boys. We do have a free weekly paper in our area that is delivered during the afternoon—by illegal aliens on foot. If paperboys are nearly extinct, so, too, is the kind of fighting that was commonplace when I was young: two boys, fairly evenly matched, meeting at a predetermined location, squaring off, and trying to beat the tar out of each other. Back in the 80’s, one of my nephews, Sean, was a senior in high school. He was an all-league football player who could be ornery at times. He got in a few altercations at parties and other venues where teenagers gathered. Yet, he told me that fights were infrequent and that a scheduled fight—as opposed to some spontaneous eruption at a party—was a rare event. Both forms of fighting were common when I was young.

Fights were affaires d’honneur. It was usually about nothing more—but then nothing counts more—than who was tougher. Fighting began in grammar school. Everybody knew who was toughest in the fifth and sixth grades, and who was second toughest, and third. Given class photos, I could still list the top half-dozen in each grade. It was everything to us at that age. The rankings were not arbitrary but based on numerous fights. Any new guy in school was immediately put to the test—if he thought he was tough. “Do you think you can take Tom? How about Mike?” If he answered in the affirmative, a fight was scheduled for after school. The fights only got better in junior high and high school.

Little was ever done to stop any of these fights. They occurred between two willing scrappers without weapons. Most fathers approved. Most mothers remained silent. There were exceptions, of course, perhaps foreshadowing the attitude of many parents today. I remember some guy in junior high telling us, “My father told me it takes more of a man to walk away from a fight than to fight.” Every one of us who had been in fights knew that was consummate bullsh-t. We also knew that the kid’s old man must be a coward. Fighting was an act of great courage, especially when you had to think about it for a day or two or sometimes a week before a scheduled event. There were no guarantees of victory, and, by junior high, guys were big enough and strong enough to injure their opponents—seriously. Broken bones—noses, jaws, hands, fingers, and arms—were common, as was the loss of teeth. Even if a guy lost a fight, he was respected just for showing up.

Such a fight occurred in high school between “Mugsy” Green and Bill, a kid who had recently transferred from an Eastern prep school. Bill had done or said something that caused Mugsy to challenge him to fight. To everyone’s surprise, Bill accepted. Although Bill was more than a half-foot taller than Mugsy and seemed to be in reasonably good shape, he looked like what he was—a prep-school boy. Mugsy, on the other hand, was not given his nickname by accident. He had a very prominent Celtic chin and the demeanor of Jack Dempsey. Standing not much over 5’6”, he was 165 pounds of muscle, bone, and sinew. He appeared to have been chiseled out of granite. Put Levis and a T-shirt on a pit bull and stand him upright, and you have Mugsy. When we all started boxing, years before at the local park under the direction of “Mac” McDougall, Mugsy hit Mac so hard during a sparring session—and we were using big, heavy gloves—that it almost lifted Mac off his feet. Mac was shocked that a kid could hit so hard. The rest of us were already well aware of the fact.

As a sizeable crowd gathered at the designated location for the fight, Mugsy casually leaned against a car and told stories. He was one of the best storytellers I have ever known and had a sense of humor that was a combination of George Carlin and Don Rickles. Mugsy could leave us laughing until our guts hurt. When the scheduled time for the fight passed and Bill had not arrived, smart money was betting that he would be a no-show. Just about then, prep boy arrived in a car driven by his father. Mugsy looked disgusted and said sarcastically, “He’s brought his daddy.” To our surprise and amusement, Bill inserted a mouthpiece and then began doing a series of warm-up exercises. The Mugs could not believe what he was seeing and exclaimed, “What’s this sh-t?!” The crowd roared.

Bill finally announced that he was ready to fight. Mugsy took off his jacket and stepped forward as Bill began to move and jab. He had obviously done some boxing. Mugsy slipped or deflected the jabs, got within range, jabbed and feinted, and let a tremendous left hook rip. It landed flush on Bill’s jaw and sent him to the ground. Mugsy looked down into Bill’s glassy, unfocused eyes and said, “I didn’t think he’d show up. He’s got guts.” The fight had lasted less than 30 seconds, but prep boy gained a lot of respect.

Good high-school street fighters gained reputations that spread from local neighborhoods and towns through Los Angeles and even Southern California. During the mid-50’s, the McKeever twins, Mike and Marlon, who lived near Westwood but went to a Catholic high school in Ccntral Los Angeles, had fearsome reputations for fighting. They both went on to become All-American football players at Southern Cal. A year or two later, Santa Monica was talking about the O’Mahoney brothers and Owen “Megaton” Miller. Up in the Palisades, we had O.T. Crippen and Pat O’Neal. O’Neal, later known by his middle name Ryan, was one tough fighter long before he appeared in the television series Peyton Place and then in such movies as Love Story and What’s Up Doc? His father, “Blackie” O’Neal, had him training in boxing gyms years before he was taking acting lessons. His mother, Patricia Callaghan O’Neal, an actor herself, did not interfere. If Pat O’Neal had been a little bit bigger, he might have seriously pursued a career in boxing. With no cruiserweight division in those days, he found himself a bit big for the light-heavyweight division and a bit small for the heavyweight.

O’Neal had a wild temper and fought frequently. He was fast, had a good punch, and was fairly well trained. Later in life, his movie roles—such as a quiet, bumbling, retiring professor playing opposite Barbara Streisand—were stunningly incongruous for those of us who knew Ryan O’Neal when he was Pat. The O’Neals lived only about a half-block from my family, and Pat’s little brother, Jeff (who would later go by Kevin), was in my grade at school. He was a smaller, red-haired, red-faced version of Pat. He had the same uncontrollable temper but was not nearly the fighter, which was fortunate for me because I fought him three or four times.

Pat, meanwhile, was knocking the stuffing out of most of those he faced. One of his best fights occurred in a vacant lot across the street from Vince’s barbershop in the Palisades. Dave Diaz was considered one of the big baddies at University High in West Los Angeles, where O’Neal attended. In a powerful display of well-thrown punches, O’Neal battered Diaz into submission. O’Neal then turned to one of Diaz’s buddies, Greg Latta, and asked him if he wanted some of the same. Latta, a well-built guy about O’Neal’s size, assented, and a second fight was on. O’Neal should have quit while he was ahead. Latta had a wickedly quick and accurate jab and kept the tired O’Neal off balance. O’Neal’s punches lacked the steam and the accuracy that they had in his first fight. Nonetheless, he kept firing, occasionally landing a blow, and Latta kept jabbing and peppering O’Neal’s face. Finally, with both fighters exhausted, they called it quits. Those in the crowd had gotten more than their money’s worth.

For weeks afterward, O’Neal’s fights were the topic of conversation in the Palisades, especially in Vince’s barbershop. We younger kids could see that the men simply relished the fights. I never heard a negative word about the violent two-for-one encounter in the center of town. There was praise for the fighters and speculation about upcoming fights.

A few years later, when I reached high school, my good buddy Scott McKenzie was the rising star of street fighting. He had already gained a fearsome reputation in junior high. By the ninth grade, he dominated the school. The principal finally expelled him for one too many fights. When he arrived at a new junior high, he found that some fellows who knew about him had already lined up a fight for him with the school’s toughest guy. The two of them did not even make it to the end of the schoolday before they were tearing into each other. Scott’s first day at the school was his last. He then went to a junior high in a different school district. He lasted three weeks before he was goaded into a fight with the school’s number one badass. Scott pummeled him senseless. With a promise of good behavior, Scott was allowed to return to our junior high so he could graduate.

In the tenth grade, Scott, only 15 years old, was a two-way starter at tackle on the varsity football team. He tipped the scales at 225 pounds, yet was lean at that weight. He was not only the strongest but the fastest lineman on the team. Imagine Dick Butkus in high school, and you have Scott. Like Butkus, Scott loved to hit, to punish, to inflict damage. When he got his anger up, which was not infrequent, he was a force of nature. By the time he was a senior, he had fought and battered the best fighters at all the surrounding high schools. He then began to fight guys in college—wrestlers, football players, martial artists—anyone who thought he was tough.

One night, Scott and I got word that there was a UCLA fraternity party at a house up in Stone Canyon. The fraternity was hosting their sisters from the hottest sorority on campus. We were given a name to drop to get in the door. We rode to the party on our motorcycles—Scott, on his BSA; I, on my Matchless. That was a mistake, because it drew some attention to us. Soon, the fraternity brothers began asking one another, “Who are those two guys who drove up on the motorcycles?” It only got worse when we started dancing with their sorority sisters.

Quickly it was decided that “Animal,” a bouncer legendary among the fraternities at UCLA, should eject us. I have to credit Animal for guts, if not for brains, because he walked up to us, ignored me, and focused on Scott. “You guys are leaving,” Animal grunted. Scott stretched out his left arm, holding his hand in front of Animal’s face and said, “Back off, pal.” Animal, a ferocious character who had earned his nickname for such things as biting off ears, grabbed Scott’s arm and chomped down on Scott’s hand. Scott had badly injured the hand in an accident, and Animal happened to bite down on a metal plate holding bones in place. Not only would Animal’s front teeth never be the same, but Scott now had him just where he wanted him. A crashing right hand sent Animal tumbling backward and sliding across a patio. The fraternity brothers stood in stunned disbelief: Not only had Scott showed no pain when Animal took his bite, but Animal had been knocked senseless. We strode out the front door—Scott was a great buddy to have in times like those—kick-started our bikes, did a few donuts on the front lawn for good measure, and roared off down the canyon.

Just when and why this all changed is not entirely clear. Part of it has to do with the drug culture of the late 60’s and early 70’s. I remember returning home from the service and seeing nearly everyone stoned and mellow rather than juiced and aggressive. All of a sudden, it had become cool to be pacifistic and cowardly. However, the drug-addled hippy-dippy counterculture faded rapidly with the end of the draft and with our withdrawal from Vietnam. A masculine culture might have returned but for a new movement. By the early 70’s, the unfeminine feminist movement was gaining momentum: Men were evil (at least white men); strength and aggression were bad; competition was wicked; testosterone was pathogenic. Boys were no longer allowed to be boys and were punished in school unless they acted more like girls—sitting still in their chairs, paying attention to the teacher, not talking, not hitting, and not disrupting. If not, Ritalin was prescribed. Somehow, it was forgotten that we could get reasonably good behavior from boys if they were allowed to play fiercely competitive games at recess and to wrestle and punch one another until exhausted.

Once upon a time, we were a warrior race, honor-bound to stand and fight. In the Gaelic clans of old, “brother fought beside brother, father by son, so that each might witness the other’s courage and valour and find example in them.” Boys knew this was part of their destiny from childhood on—they had an instinct for it, and it was expected of them. Now, we try to feminize our boys, weaken them, even emasculate them. Fighting is left to craven inner-city gang members who rarely face off one-on-one and fight fair-and-square but, instead, shoot some unsuspecting gang rival while he loiters in front of a convenience store. Soldiering is left to a few professionals who do what every male—when we had an army of militia volunteers or citizen-soldiers—was formerly expected to do. We are undergoing the same kind of evolution—or devolution—that Rome experienced, only doing it so much faster. It is not an irreversible natural phenomenon, though. Man has done it, and man can undo it. It all begins with allowing boys to be boys—so that, one day, they can be men.

Leave a Reply