This article first appeared in the December 1987 issue of Chronicles.

American conservatism in the late 18th century was unlike the European species, where popular “peasant” and articulate “aristocratic” conservatism were able to develop together and to maintain a common front against the ascendant bourgeoisie. With the exile of loyalists and the waning of the old Federalists, American conservatism was effectively decapitated; nevertheless, a popular conservatism continued to endure in the subnational practices and institutions of the American commons.

As a result, it is a serious mistake for conservative intellectuals to search for legitimacy in the thinking of the Founding Fathers and their national Constitution. Rather, the roots of American conservatism should be sought in the ethical tradition of popular democracy, and not in any abstract rational project. It was the majority of Americans living in villages who in the founding period and thereafter upheld this conservative ethical vision against encroachment. From the late 18th century on, two ethical visions—nationalistic liberalism and parochial consensual democracy—would vie for the soul of America. The American national republic and its “creed” were thus born bifurcated.

It is this local-centric America, and not any nationalistic “conservative” elite (though one still did exist in the late 18th century), that is the source of an indigenous American conservatism. But it was amorphous and inarticulate, existing mostly at the level of village norms and practices.

The Republic came into being with its language, high culture, and national identity supplied by an increasingly liberal bourgeois elite. Its popular culture and widespread practices, on the other hand, stemmed from a distinctly different, local-centric commons whose communitarian ways continued to be renewed until the 1920’s by wave after wave of European peasant immigrants.

Why “peasant”? My answer is that while aristocratic conservatism was not viable in America after the Revolution, the popular conservatism of the commons was very much like a European peasantry’s variant of conservatism. In the European case, however, the peasantry’s conservatism was overshadowed by the more visible aristocracy. Social classes in America were in contention, but, unlike Europe, the nascent American aristocracy was easily vanquished, leaving only the national bourgeoisie and the provincial commons as the contending forces.

American conservative localistic forces are often transmogrified into radical progressive forces. There should be no confusion here: The commons of America were reactionaries trying to maintain almost medieval social norms. They were communitarian and religious; they relied on personal relationships and prized ethnic and religious homogeneity.

Since the late 18th century, “peasant”-like populations in America resisted the forces of modernity in an attempt to preserve their premodern world of communitarian values. And associated with their largely agrarian institutions was an ethical vision of man that was antithetical to the emerging liberal view. Greater than his wants and passions, man was challenged to overcome himself either through surrender to God or through his actions as a citizen.

Of course, the forces opposing this parochial mind were composed of the small minority willing to embrace modernity; they were representatives of the same class that has so effectively controlled American historiography that parochialism is seen only as a force in opposition instead of as a competing and antithetical ethical system.

Late 18th-century America was not yet a liberal bourgeois world of nationalism and individualism. It was a world of conservative communities that intruded everywhere upon the individual.

Although conservative minds have always existed, it really makes little sense to talk about conservative political theory before the end of the Enlightenment. It was not until upper-class conservatism had lost its influence that American conservatism became self-conscious! Conservatism, then, was initially an attempt to maintain a certain world view that still had widespread acceptance in Europe. But it was only when it came under intellectual and political attack that conservatives were forced to create a set of consistent abstractions that we have come to know as philosophical or transcendent conservatism.

No bourgeois political party in America has ever espoused a conservative vision, and outside the literary circles, articulate conservative discourse did not exist until after World War II, when, ironically, popular conservatism may have already been fatally corrupted.

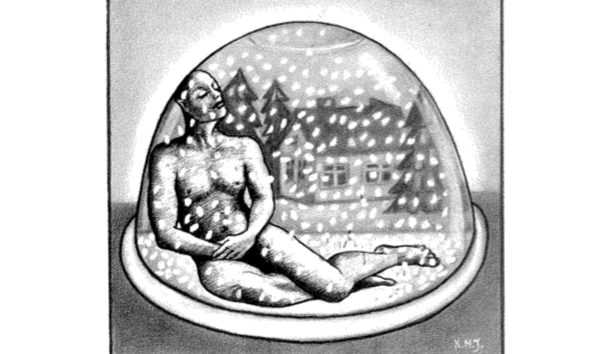

Philosophical conservatism holds three axioms as essential: The first of these dogmas is a pessimistic view of human nature in which man and society are understood as products of the Fall. From this perspective, man is not perfectible: Society can be ameliorated but can never be perfected. Man is a tragic figure who can never be allowed total freedom.

Associated with this tenet is the concept of liberty. From the conservative view, liberty is conceived as freedom from sin and uncontrolled passion, in ways very similar to the Christian and republican perspectives that were widespread in colonial and early modern America. As Goethe put it: “Everything that liberates the spirit without a corresponding growth in self-mastery is pernicious.”

The second dogma is conservatism’s organicism and its communitarian ethics. From the conservative perspective, if a conflict develops between the intrinsic values of community and the individual, the community—which represents the higher moral end—takes precedence. The community is prior to the individual not only morally but also historically and logically. Not only is the community a higher end but, in the conservative’s view, the concept of a totally free individual is also an illusion.

Society is an organism, and man participates in this historic living entity only as part of an estate, a corporation or some such subordinate grouping, outside of which the individual has no standing.

Conservatives and romantics are understandably drawn to the Middle Ages, but this medievalism is only rarely a vulgar desire to recreate the actual institutional conditions of the medieval world; it is more frequently an attempt to understand the universal principles embodied in the medieval world’s Christian sensibilities. This premodern vision is opposed in the conservative’s mind to modernity’s this-worldliness, materialism, anthropocentrism, anarchical individualism, and vulgar hedonism.

Human life, and to no less a degree, corporate (political, social, and economic) life, is understood as a moral activity. Man is a potential, situated between beast and God, and conservatism demands that it is God who must be served and that any culture not committed to that end, such as liberalism, is to be resisted.

Although conservatives disagree over the appropriate level of aggregation within which to pursue this aim, there is broad agreement that the good society must seek the perfection of its members’ souls. Furthermore, man is expected to overcome his passions in order to fulfill his responsibilities to family, neighborhood, church, and above all else, to his divine soul. In accord with this ontology, cultural and moral relativity at the individual level is explicitly rejected.

The third dogma central to conservatism is the complexity thesis, the center of conservative epistemology. Abstract rationalism and all arrogant attempts to use rational models of human and social behavior to construct political and social institutions are inherently based on a most imperfect understanding of extremely complex systems. All social projects must be approached with diffidence and constructed by slow adaptation and experimentation, by “muddling through,” to use Irving Babbitt’s phrase.

Derivative from this basic tenet is the contention that the size and complexity of centralized government must be limited because of the infeasibility of maintaining effective architectonic intelligence. It should be noted, however, the conservative has no intrinsic love of capitalism but regards it as a system of economics that does, at least in part, accord with man’s limited and diffused capacity for gathering and using knowledge-i.e., each man is best prepared to make rational choices only about his immediate community’s social, political, or economic life. But this approbation of capitalism is delimited by the society’s ethical requirements that will always take precedence over the dictates of the amoral bourgeois capitalist economic system.

These three central tenets were forcefully promulgated in practice if not in voice by the vast majority of 18th-century Americans–a conservative people, albeit an anomalously popular one.

From the conservative’s perspective, the aristocracy, and frequently the peasantry, are understood to be reservoirs of authentic communal values. Their respective corporate “self-regulation” and transgenerationality are seen as fundamental for the survival of any culture. For this reason, the conservative demands that the peasantry be distinguished from the poor urban masses who possess neither self-control nor a sense of historic responsibility. Consequently, unlike a well-established peasantry, the urban mass is not to be trusted with liberty, or its political manifestation democracy.

This “forgotten” democratic ethical tradition needs to be recovered and made articulate after having operated so beneficially as a set of localistic norms and practices for the last two centuries, because the salutary “genius” of America has been a result of the competition between the two antithetical ethical traditions outlined above.

One tradition, with its associated bourgeois class and its accompanying institutions, continuously dominated the discourse at the national level, while the other tradition, with its associated “peasantry” deeply entrenched in political and social islands, maintained a parallel and distinct universe of behavior. Nevertheless, simultaneously they were parroting the ubiquitous liberal language of the bourgeois elites. Or, as Marvin Meyers and others have observed, America after the founding period quickly be came a paradox, with an increasingly disparate reality and ideology.

However, enormous technical changes in communication, transportation, and industrial organization have upset this balance and made “mass” man possible, correspondingly increasing the empowerment of their bourgeois spokesmen. The historic balance between the bourgeois liberal elite, those that “talked”—and the conservative commons, those that “did”—has been upset.

With the 1964-65 civil rights legislation, the liberal ethical tradition finally succeeded in completely supplanting the popular American conservative ethical tradition of consensual democracy whose roots were sunk deep in the soil of the 18th century, and effectively destroyed the historic balance.

Could civil rights violations, so common in historic America, have been caused by that which has putatively cured them, that is, the hegemony of the liberal voice in national-level politics? Or put another way, was it the lack of an articulate conservative voice that explains, at least in part, the irrational and violent nature of the popular localist forces when they entered the national political arena? Was it a lack of an appropriate vocabulary and conceptual framework that made them incapable of being directed by upper-class spokesmen?

Now that the popular “unconscious lived” conservatism is no longer viable, we must create articulate ways of framing that same lived reality. In this way, alternative solutions sets might be more available to the many, in particular those solutions employing conservatism’s communalist prescriptions.

In fact, it is the absence of a clear alternative that makes choice so problematic for the average “consumer” of values. It is only by means of alternative ways of understanding themselves that Americans will be able to escape the vicious cycle in which liberal individualism leads to unattractive and unforeseen consequences, and then in the search for a remedy, are turned to the self-same pathogen, liberalism. Without a sense of alternative value systems, such as could be offered by a visible and articulate conservatism, Americans cannot understand their essential problems, let alone solve them; they are not free to find anew a satisfactory balance between the two competing normative frameworks of historic America.

Leave a Reply