The man who was arguably our finest contemporary writer passed away earlier this week. Cormac McCarthy was 89.

In his literary works, McCarthy wrestled with God and the big questions of purpose and meaning he said were the only proper subject for literature, questions he never let go of in his dark, compelling, and violent novels. Literary critic Harold Bloom called McCarthy the true heir to Melville and Faulkner. Those great predecessors, along with Dostoevsky and Conrad, influenced McCarthy’s style and subject matter, even as he mastered a unique style of his own. McCarthy took his tormented protagonists to places none of his literary heroes had gone to. He was a great soul who in his art showed himself a driven man, even a haunted one, who was totally dedicated to his vocation.

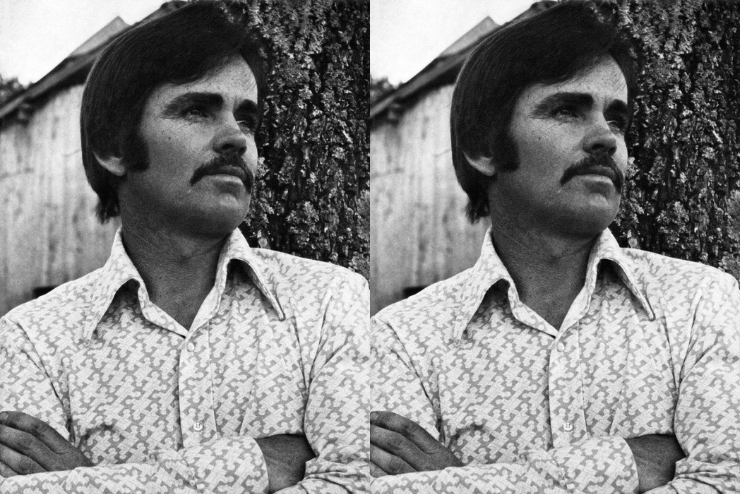

Charles McCarthy (he would adopt the Gaelic “Cormac” as his nom-de-plume) was born in Rhode Island in 1933 but grew up in Tennessee, where his father worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority. Appalachia would be the setting for several of his hillbilly Gothic novels, which recounted tales of murder, incest, and necrophilia, of lost souls in a harsh, unforgiving world. These harrowing tales eschewed standard punctuation (he once said he didn’t like all those “squiggly lines” breaking up the page), employing a language that echoed the King James Bible as well as Faulkner. His style could be spare but could also soar to poetic heights as he forged new words that seemed to emerge from the fundamental elements themselves. At his best, McCarthy’s often terrifying, but deeply religious, tales are a moving spiritual and aesthetic experience.

McCarthy lived much of his working life in obscurity and poverty, eschewing any public discussion of his art and avoiding anything that would interfere with his work. His second wife, Anne Delisle, recalls living in primitive conditions that included having to bathe in a lake. Her then-husband was so loathe to talk about this writing that he preferred privation to disclosure. “Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books,” she told The New York Times, and McCarthy would reply by saying that everything was there on the page. “So we would eat beans for another week.” He sacrificed security, and much in his personal life, in the service of his art, driven, as great literary artists are, by the compulsion to realize the stories inside them on the printed page.

For decades, beginning with the publication of The Orchard Keeper in 1965, he worked closely with Random House editor Albert Erskine, who had also edited Faulkner. Erskine stood by McCarthy, even though his books did not sell, and McCarthy developed a following among serious readers as Faulkner’s reputed heir. McCarthy was a “writer’s writer,” enjoying a certain critical success, but notoriety and financial security eluded him until the publication of All the Pretty Horses in 1992. All the Pretty Horses was a best seller and won the National Book Award. The Crossing and Cities of the Plain followed, filling out the “Border Trilogy” that established McCarthy as a noteworthy author with the broad reading public.

All the Pretty Horses was McCarthy’s most commercial novel up to that time, and it was the first of his books that your humble servant read. John Grady Cole’s odyssey, in effect a mythic journey to the underworld that transforms the hero, caught my attention. I backtracked, reading his previous works. It was an eye-opening literary journey. Jim Ruland, writing an “appreciation” of the late author’s work in the Los Angeles Times, recalls that his exposure to McCarthy was something of a shock. According to Ruland, “I didn’t know of anyone—alive or dead—who wrote like McCarthy. I didn’t know you were allowed to write like McCarthy.” Neither did I—it was not only McCarthy’s style, but the magnetic pull of his willingness to go to places in the heart of darkness that Melville, Conrad, and Faulkner couldn’t that drew this reader in.

Man in his extremity was McCarthy’s opportunity to delve deeply into humanity’s capacity for violence and evil, as well as an elusive, but ever present, chance for redemption. Good appeared in the most unlikely places, while death waited in the shadows, ready to spring on passersby in the form of apostles of destruction such as Child of God’s Lester Ballard, a serial killer who lives in caves. A malevolent preacher and his psychopathic disciples wreaked havoc in Outer Dark. A Luciferian prophet called “The Judge” in his masterpiece, the bloody existential Western, Blood Meridian, preached his own gospel of mass destruction, and Anton Chigurh, the philosophical assassin who goes on a violent rampage in No Country for Old Men, used a coin toss to decide the fate of his hapless victims.

Blood Meridian, based on the history of a gang of scalp hunters, heralded a shift of locale for McCarthy from Appalachia to the American Southwest. The majestic, bleak moonscapes of the desert Southwest are described in geological detail, the beauty and strangeness of nature at once life-affirming and red in tooth and claw. It’s a fit setting for the apocalypse that follows the Glanton gang like an outbreak of the Black Death, and the unlikely vessel for hope that is the Kid, who sets himself on a collision course with the Judge. The Judge’s philosophy of war is totalitarian, demanding the acquiescence of all the players in the Great Game he describes in some detail in his ruminations to the gang:

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

The judge smiled. Men are born for games. Nothing else. Every child knows that play is nobler than work. He knows too that the worth or merit of a game is not inherent in the game itself but rather in the value of that which is put at hazard. Games of chance require a wager to have meaning at all. Games of sport involve the skill and strength of the opponents and the humiliation of defeat and the pride of victory are in themselves sufficient stake because they inhere in the worth of the principals and define them. But trial of chance or trial of worth all games aspire to the condition of war for here that which is wagered swallows up game, player, all.

Chance, determinism, and free will are constant themes in McCarthy’s work. The Janus-like duality of good and evil took on a Manichean aspect in his books, God and the Devil ever present as between-the-lines characters. Yet McCarthy held out the possibility of some hope in a world that condemns each of us to death.

In The Road, an unnamed father and his son struggle to survive a world that has been literally reduced to ashes by an unspecified catastrophe. The father is determined to protect his son from the gangs of cannibals who roam through the wasteland. He dies having delivered him to a group of survivors who have retained their humanity. In this passage, the boy sees his dying father for the last time:

He walked back into the woods and knelt beside his father. . . . He cried for a long time. I’ll talk to you every day, he whispered. And I won’t forget. No matter what. Then he rose and turned and walked back out to the road.

The woman when she saw him put her arms around him and held him. . . . She would talk to him sometimes about God. He tried to talk to God but the best thing was to talk to his father and he did talk to him and he didn’t forget. That woman said that was alright. She said that the breath of God was his breath yet though it pass from man to man through all of time.

Haunting images of fathers and sons appear elsewhere in McCarthy’s work.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell in No Country for Old Men faces a dire situation he cannot cope with in a country quickly descending into an abyss. But the light is still there. In a dream of his father, Ed Tom sees him riding through a pass in the mountains carrying fire in a horn:

I knew that he was going on ahead and that he was fixin to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there.

McCarthy has been hailed as a dark genius, but I see him as a light bearer in a harsh world. With his books, he has acted as the man carrying the fire through the cold and the darkness. Like many seeker-artists before him, I think McCarthy’s life was more about the journey than the destination, about answers he would never definitively find, about choosing what kind of life meant something, and never giving up on it. There is a school of thought that contends that the bleakness and stark violence of his work is nihilistic, but anyone who has spent time reading the body of his work should know better. As I wrote in a Chronicles piece on McCarthy’s The Passenger, just released last year, and his career and place in American letters, “It is impossible to think that a man who has written such moving, terrifying, inspiring prose could ever believe he was engaged in a futile act.”

McCarthy is gone, having secured his place in the literary canon. May he rest in peace.

Leave a Reply