Tom Ditzler, a veteran, buys 30 acres of rural farmland. For 50 years, he and his wife, Jan, live there, rearing two children, Cassandra and Christina. Tom comes to know the contours of his property by heart—the creek that runs across his land, the wetlands surrounding the creek, the hills and woods that rise up from the creek bed toward his house. Though legally blinded when a mortar misfired during an Army training exercise, Tom can walk his property without assistance. He can even drive a truck through portions of it.

Then, one day, everything changes. County officials notify him that they are going to build a road across his land. In the name of economic progress, they will take 17 of his 30 acres through eminent domain. The road will cut him off from the creek, from the wetlands, from the hills. It will run right past his house, less than 100 feet away. The world that he has known for 30 years—the property that has restored a measure of the freedom that he lost along with his sight—will suddenly become much smaller.

A young black jazz musician lives with his grandmother in a house that his family has owned for many years. In a neighborhood that would politely be called “marginal,” Henry Hamberlin and his grandmother have kept up their home with a quiet sense of dignity. The woodwork has been immaculately kept, and the original gas lamps still work.

Then a federal judge comes along and declares that the local public schools have “raised discrimination to an art form.” One of his solutions? Increase taxes dramatically to pay for the construction of elaborate-and expensive—schools in historically black neighborhoods. But Henry’s house stands in the way of rectifying racial wrongs. The school district cannot take his home, so the city begins eminent-domain proceedings. The city offers him a fraction of what it is worth, basing its value on similar—but less well kept—homes in the neighborhood. Where Henry’s house once stood, the support staff at Ellis Fine Arts Academy now park their cars.

A sanitary-sewer district notifies residents in a rural area of the county that it will be using eminent domain to gain permanent casements across the front of their property. A sewer trunk is coming through to service a subdivision proposed by a wealthy contributor to local political campaigns. Although the sewer could be run through farmland on the opposite side of the road—and the owners of the farmland have no objection—officials from the sanitary district privately admit that they want to lay the sewer on the residential side of the road in order to make it possible for the city to annex the property, even though the sanitary district has no official ties to the city government. Without the sewer running through their front yards, these property owners might eventually end up as a pocket of the county surrounded by the city—with lower taxes and separate services.

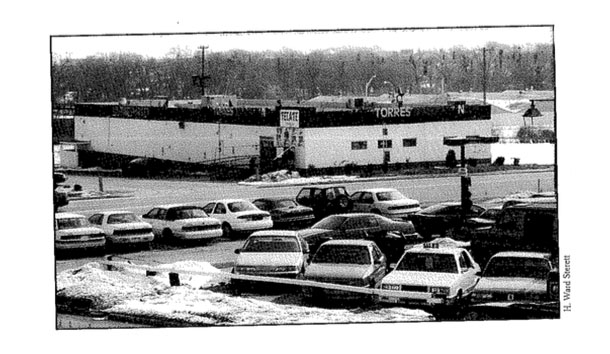

An Hispanic family buys a building in a run-down part of town. Since the riots of the late 60’s, the area has been largely dead. Now, a revival of sorts is taking place, led by the Torreses, who convert the building into a Mexican market. It is the only grocery store of any size in that quarter of the city, and thus enjoys a mixed clientele—whites, blacks, and Hispanics.

Then a local developer commissions a study to determine the feasibility of building a large grocery store where the Torres Market currently stands. After several years, he finally finds a chain willing to move into the area. Rather than approaching the Torreses and offering to buy their store, the developer goes to the city government, which begins eminent-domain proceedings on the Torres property and a half-dozen others. Once the city gains title to the Torres Market, it will hand it over to the developer, who will have eliminated the only competition for his chain supermarket.

I could multiply examples of eminent domain almost ad infinitum while never once leaving the boundaries of the City of Rockford, Illinois, and Winnebago County. In fact, the four examples that I have just cited have all taken place within the past two years in an area of the city and county no larger than a couple square miles—and for every case that I have mentioned, at least a half-dozen other eminent-domain proceedings have occurred in that tiny corner of our community.

The language of the Fifth Amendment seems so innocuous—or, rather, it seems a positive good, designed to protect us: “No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” But how do we get from there to the Torres Market?

Traditionally, in order to exercise the power of eminent domain, government has had to show, first, that it was taking the land in order to use it for a public good; and second, that there was no other pareel of land that could be used for this particular project. When we hear the words “eminent domain,” most of us probably think of roads and canals. While the Ditzlers’ case involved the use of an Illinois state law called “Quick Take,” under which municipalities can seize a man’s property first and negotiate a price later, it was still a fairly straightforward example of the use of eminent domain for a so-called public good. Of course, as with any public good, some will benefit more than others from the road that now rims across the Ditzlers’ farm; Property records show that wealthy and politically connected developers own most of the land on both sides of the road. Had it been rerouted to run up an existing road a few hundred feet to the east, the developers would have been shut out.

Henry Hamberlin’s ease is also an example of a fairly traditional use of eminent domain. After roads, public buildings (especially schools) probably account for most of the instances of eminent domain. The irony is that a black family lost its ancestral home in order to rectify years of supposed discrimination against blacks. The “public good” in this case was definitely not a private one.

In the last two examples, however, things start to look gray. While a plausible argument can be made that sanitary sewers are a public good, the people through whose yards the sewer is being run are receiving the benefit only incidentally: I They will be hooked up to the sewer “I (partly at their own expense) because the law says that the sewer is too close for them not to be hooked up. But the real point of the sewer is to allow a new subdivision to be built in order to enrich a developer. How, exactly, is that a public good?

And what about the Torres Market? In the other cases I have cited, private citizens have benefited (or been hurt) in the name of the public good, but in each case, the land taken by eminent domain remained in the hands of government—a condition that seems to be implied in the Fifth Amendment clause “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” But when the City of Rockford acquires the Torres property, it will immediately hand it over to a private developer. How, then, can the use of eminent domain be justified?

The answer is simple: If eminent domain can only be employed to take land for a public use, then all the city has to do is expand the definition of “public use.” Charles Box, our outgoing mayor, claims that the southwest quadrant of Rockford needs a full-service grocery store, and he is probably right. He also believes that the Torres Market is not large enough to serve all the residents of the area, and that may be true. But even granting the mayor’s arguments, how can they possibly justify taking land from one private owner and handing it over to another?

About a year ago, shortly after the City of Rockford announced that it was initiating eminent-domain proceedings against the Torreses, I appeared on a local TV talk show with Barbara Richardson (the city’s director of community development at that time). When the conversation turned to the city’s attempts to confiscate the Torres Market and other properties, Miss Richardson explained that she believed in a very expansive use of eminent domain: “If you believe that government has any role in economic development, then you must believe that government can do whatever is necessary in order to facilitate economic development.” Even, apparently, redistributing private property.

Rockford has not been alone in expanding the use of eminent domain. Detroit pioneered the concept almost 20 years ago, when it condemned the entire Poletown section of the city and handed the property over to General Motors for use as the site of a new automobile plant. More recently, the Institute for justice, a Washington, D.C.-based conservative legal foundation, has represented clients in similar eases in both Atlantic City and Pittsburgh.

But the seeds of this expanded use of eminent domain were there from the beginning. The construction of roads and canals (and, later, railroads and the Interstate Highway System) was not an unadulterated public good, and not simply for the reasons that Bill Kauffman outlines in his book. With Good Intentions? Reflections on the Myth of Progress in America. In fact, whenever eminent domain was used to procure the land for a road or a canal, someone disproportionately reaped the benefits from it. For most projects that truly benefited the public at large, eminent domain was not used—for instance, to construct roads from rural areas into towns, so that farmers could bring their crops and livestock in for sale. Instead, the farmers themselves constructed those roads, and they did not even charge tolls.

At the time of the American founding, this use of eminent domain made perfect sense; the Framers of the Constitution, after all, were mercantilists, concerned more with the wealth of nations than with the wealth of private citizens. Anything that could (in President Clinton’s hackneyed phrase) “grow the economy” contributed to the wealth of the nation. Still, the Framers would never have countenanced the use of eminent domain to take property from one citizen in order to give it to another. It took the development of capitalism—specifically, state capitalism—before government could come to identify a private good so completely with the public good.

When Barbara Richardson expressed her fondness for eminent domain, she was speaking not as a socialist, but as a state capitalist. Miss Richardson truly believes in private enterprise; during her tenure in Rockford, she devoted much of her efforts to encouraging the founding and growth of small businesses. But for her, and for other state capitalists, property is nothing more than a commodity. As long as we properly compensate the owner, why should government not take property by eminent domain and hand it over to someone else, who will use it with greater economic efficiency?

Why indeed? One of the reasons that property owners have found it so hard to get up the will to fight eminent-domain cases in recent years is that this idea of property as simpK a commodity has become the prevailing view, even among—or perhaps, especially among—the defenders of private property. I once heard James Bovard begin a speech by declaring that the most important quality of property is the ability to sell it. His point, of course, was that government regulation often infringes upon this ability. As I glanced around the roomful of libertarians, I noticed them nodding their heads vigorously in agreement. But while his statement may be true in the limited confines of a market setting, another quality is far more important, because it relates to the whole of human existence, not merely its market aspects. Contra Bovard, the most important quality of property is the ability to keep it. Today, this quality is even more endangered than the ability to sell it.

The economic security that comes from owning one’s land and home free and clear, the rootedness that comes from living in the same place over a long period of time, the potential for personal and community self-sufficiency that such rootedness provides—all of these have no value when property is viewed simply as a commodity, because they can be assigned no value by the marketplace. And yet these effects of property ownership provide the greatest possible protection against economic and political centralization —and the loss of freedom which accompanies it. That is why those who love liberty must first defend property.

For Christians, property can never be merely a commodity. It is, rather, an extension of our personality, as much a part of us as our wives and children. As Eastern Orthodox Bishop Kallistos Ware points out, we are the true materialists, because, by acknowledging the Incarnation of Christ, we recognize the importance and dignity of the material world, and our integration within it. “The earth is the LORD’s and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein” (Ps. 24:1). To regard property as merely a commodity is a form of consumerism, a spiritual disease which is anti-materialist and, therefore, anti-Christian.

But consumerism is the religion of the day, and the apostles of Homo economicus, both socialist and capitalist, want us to be ashamed to view ourselves as anything other than consumers or to view our property as anything more than a commodity. Business cycles flatten out and marketplaces function more smoothly when we all act like good automatons, in accordance with supposed economic laws. When we let ourselves be ashamed at having any loyalties that are deeper than our ties to democratic capitalism, we become unable to defend our property as ours—for keeps—and government and developers can put a monetary value on something that should be as invaluable as a family member, or one of our limbs.

When he wrote one of his finest poems, “Do Not Be Ashamed,” Wendell Berry was thinking not simply of property rights but of the growth of a broader political and economic totalitarianism. Still, his words are appropriate here:

You will be walking some night

in the comfortable dark of your yard

and suddenly a great light will shine

round about you, and behind you

will be a wall you never saw before.

It will be clear to you suddenly

that you were about to escape,

and that you are guilty: you misread

the complex instructions, you are not

a member, you lost your card

or never had one. And you will know

that they have been there all along,

their eyes on your letters and books,

their hands in your pockets,

their ears wired to your bed.

Though you have done nothing shameful,

they will want you to be ashamed.

They will want you to kneel and weep

and say you should have been like them.

And once you say you are ashamed,

reading the page they hold out to you,

then such light as you have made

in your history will leave vou.

They will no longer need to pursue you.

You will pursue them, begging forgiveness.

They will not forgive you.

There is no power against them.

When the City of Rockford came after the Torreses’ market, the Torreses did not defend their property directly; instead, they cried “racism.” Now, race may, in fret, have played a role, since the community development director, the mayor, and the developer who will receive the land are all black. But ultimately, race is irrelevant. What is relevant is that the Torreses have put their blood, sweat, and tears into their store, and their store has become a part of them. When Winnebago County came after his land, Tom Ditzler did try to frame the debate in terms of property rights. Unfortunately, many well-meaning but misguided supporters tried to convince him that the way to keep his land was to talk about its “ecological significance” or the extremely remote possibility that the property contained Indian burial grounds. While both of those may be arguments for keeping the land pristine, they are not arguments for keeping it his. The reason for keeping it his is that there is no amount of money in the world that could possibly compensate Tom for government essentially taking his sight a second time, after he has spent 30 years regaining it (in a sense) through his intimate daily contact with his land. For a so-called public good, which is really just the private good of some politically well-connected developers, Tom Ditzler is being shut inside the box of his blindness.

I saw Tom a couple of months ago at a party for Suzanne Lee, a former radio talk-show host who had championed the cause of Tom and others like him. As he prepared to leave, Tom reminded Suzanne that, when she first came on the air, he used to call her program to take issue with some of the other callers, who he thought were running down the country for which he had sacrificed his sight. “I used to tell them that things weren’t as bad as all that,” he said. “But now,” he conceded, “I’m afraid that they were right all along.”

Tom may feel shame; but if he does, it should be for his country, not for himself He may have lost, but he still fought the good fight. He tried to keep his property from becoming a commodity, interchangeable with the few paltry tax dollars that Winnebago County will deposit in his bank account once the quick-take case makes its way through the courts. But as I stood there listening to this veteran lament the fate of his country, I recalled a passage from Wendell Berry’s book Home Economics, and I realized that America itself had lost something when Tom’s land was taken from him. As Berry writes:

Millions of people . . . who have lost small stores, shops, and farms to corporations, money merchants, and usurers, will continue to be asked to defend capitalism against communism. Sooner or later, they are going to demand to know why. . . . People, as history shows, will fight willingly and well to defend what they perceive as their own. But how willingly and how well will they fight to defend what has already been taken from them?

I do not know the answer to Berry’s question, but I do know this: A regime that can make a patriot like Tom Ditzler feel betrayed by his country can no longer count on the unconditional lovalty of its citizens.

Leave a Reply