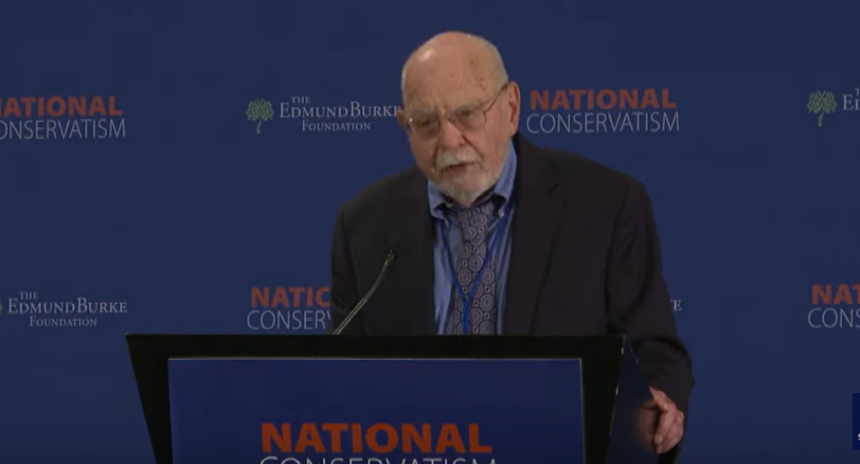

The following speech was presented at the third annual National Conservativism Conference, held in Miami from Sept. 11 to Sept. 13. Paul Gottfried gave the lead-off presentation for a panel on fusionism during the afternoon of Sept. 13.

Ever since I can remember, fusionism has been a reference point for those trying to make sense of the American conservative movement. Although not entirely one man’s creation, an embattled anti-Communist and spirited debater, Frank Meyer, gave fusionism its first form. It was Meyer who in 1962 produced In Defense of Freedom, an exposition of fusionism in which American conservatism was presented as a blending of individual freedom with inherited moral authority. Both principles were seen as grounded in Anglo-American political and moral tradition, which supposedly stressed the paramount value of the individual.

After the publication and distribution of his book, Meyer was exposed to sharp rebukes, particularly from the Christian right, representatives of which objected to his confounding of individualism with the Christian doctrine of the person. Willmoore Kendall mocked the book for being overly doctrinaire, while Russell Kirk, who had tangled with Meyer previously, complained that Meyer’s attempt to present himself as the theorist par excellence of the conservative movement exposed him as an arrogant ideologue. Behind this endeavor to fuse freedom with tradition and to create a synthetic American conservatism was someone whom Kirk accused of being “filled with detestation of all champions of authority,” indeed, someone who was trying to “replace Marx with Meyer.”

This scolding should have been expected since roughly a third of Meyer’s polemic is directed against the “New Conservatism,” which was then associated with Kirk. Meyer portrays traditionalist communitarians as the right-wing counterparts of his hated “liberal collectivists.” Both fail to recognize that the individual is “the locus of society,” and each seeks in different ways to keep the Leviathan state unfettered.

Faced by these censures, Meyer suggested that his work resonated better with those who came out of an Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture than with his snarling Catholic detractors. But there is no evidence this group was more attracted to Meyer than his other critics. We might also observe that some libertarians were deeply displeased with his theoretical construction. The anarcho-libertarian Ronald Hamowy expressed strong disagreement in Modern Age with Meyer’s intended “middle way” between authority and liberty; and from what I can gather, the great Friedrich Hayek was equally unhappy with how close to neoconservatism Meyer placed his intended fusionism.

Fusionism’s creator refused to abandon his project despite these rebuffs, and two years later, he brought out an anthology of essays that was aimed at lowering temperatures on the right. In preparing this anthology, What Is Conservatism?, Meyer made sure it was he who provided the concluding essay, which stated those broad principles on which all conservatives were supposed to agree. These included “opposition to the growth of government power” and “leveling egalitarianism” but also an emphatic rejection of “the presently established national policy of appeasement and retreat before Communism.” Meyer’s model conservatives would “stand for firm resistance to Communism’s advance and for a determined counterattack as the only guarantee of the American Republic and of our institutions generally.”

This presentation was at least partly a response to a concern expressed in 1964 by theologian and political philosopher John Hallowell that conservatives “are having difficulty agreeing with themselves as to what they stand for.” Meyer attempted to address this concern by cataloguing those beliefs that Americans who called themselves conservatives might or should have shared in 1964. Quite significantly, at the core of this belief cluster was fighting the Communist enemy and prosecuting that struggle with far more determination than postwar presidents had shown until then.

We may properly ask how this Herculean goal could be achieved without putting on the backburner the struggle against centralized federal power. The contradiction between these affirmations, however, may never have entered the author’s mind. Meyer, a fierce anti-Communist who had once been a dedicated Communist himself, believed passionately in an expanded military crusade against the enemy. But he hoped this undertaking would not interfere with either dismantling the welfare state or strict constitutionalism in most other areas of government activity. His friend William F. Buckley was less sanguine about this juggling act and at least once frankly admitted that the U.S. would have to live in what amounted to a police state for the duration of the struggle against the Soviet Empire.

The common mission for Buckley, Meyer, and others who founded National Review in 1955 and who fashioned the postwar conservative movement was anti-Communism and the hope of seeing the Cold War pursued more aggressively. NR’s conspicuous devotion to Senator Joseph McCarthy and his crusade against Communists in American government and the military flowed from this preoccupation. Although some figures associated with the magazine did not share that characteristic militancy (Russell Kirk comes immediately to mind), no one who repudiated the common goal would survive as an NR contributor. In the 1950s and even later, Buckley pronounced a ban of excommunication on antiwar libertarians, including Murray Rothbard, Ron Hamowy, and perhaps less explicitly, Frank Chodorov. Even the expulsion of the John Birch Society from the National Review fellowship, a ritual that covered most of an issue in July 1965, was based partly on divergent views about the Cold War. The Birchers opposed the Vietnam War as wasted American energy and sought to focus on the domestic Communist threat exclusively.

This isolationism was not peculiar to the Birchers’ brand of conservatism but an essential characteristic of the Old Right that had existed in the U.S. during the interwar years. When the late Ralph Raico praised Chodorov as “the last of the Old Right greats,” he was recognizing what, for Raico, was the legitimate American Right, the anti-New Deal isolationist one. Opposition to American involvement in foreign wars was foundational for what had once been viewed as American conservatism. The America First movement, which tried to keep the U.S. out of the European war in 1940 and 1941, was not composed entirely of Old Right supporters. Quite a few members, as Justus Doenecke documents in his work on this movement, came out of the American left. But the anti- interventionism promoted by the America Firsters did not differ significantly from that of such Old Right stalwarts as J. T. Flynn, Albert J. Nock, and Garet Garrett, all of whom identified “fascism” with military interventionists and the growing welfare state.

Although the very interventionist postwar conservative movement could accommodate inoffensive remnants of the Old Right, their opinions were peripheral to the war against Communism. An established procedure evolved for dealing with these remnants of older rightists. Postwar conservatism could be gracious toward hard-money libertarians, Southern Agrarians, Burkean traditionalists, or pro-Franco Latin authoritarians, providing this outreach did not clash with the magazine’s raison d’être, which was, of course, fighting Communism.

While Meyer’s In Defense of Freedom tells us that he will not dwell on the Communist threat because he “is concerned with the development of ideas within the Western and American traditions,” he then denounces Communism as “Nazism’s older brother,” which “dominates a third of the world and advances messianic zeal and cold scientific strategy toward the domination of the whole world.” Further, “Everything projected in this book presupposes the defeat of this monstrous atavistic attack upon the survival of the very concepts of moral order and individual freedom.”

It is difficult to discuss Meyer’s fusionism without considering his leitmotiv. Clearly, he sought to supplant an older version of the right with one specifically geared to fight and defeat “Nazism’s older brother.” Reviving the libertarian isolationism of the 1930s would not have served the present purpose, and Meyer’s fusionism was an attempt to summon into existence an anti-Communist conservatism fitting the exigencies of what James Burnham characterized as “the protracted struggle.”

Unfortunately, this effort did not succeed in winning over Kirk and those whom Meyer called, misleadingly, the “New Conservatives.” Nor did it greatly please those staunch libertarians who thought that fusionism was making too many concessions toward traditionalists. There was also no praise for Meyer’s theorizing from Burnham, that political realist and neo-Machiavellian who may have regarded fusionism as mere metaphysical twaddle.

One might retort to my argument that there were other forms of fusionism beside Meyer’s, and some of these variants may have worked better to advance conservative unity. Ronald Reagan may have been practicing his own fusionism when he spoke about the “tripod” upon which the Republican Party and American conservatism both rested. This tripod consisted of a defense of the free market, military preparedness, and traditional social values. Although Reagan was more rhetorical and less theoretical than Meyer, his formulation seems to have aroused less opposition.

Even more relevant, as George Nash points out in his magnum opus on the postwar conservative intellectual movement, is that Buckley in the 1960s praised Meyer’s attempt to outline the “conservative consensus.” Obviously, there was something substantive that brought together those who identified themselves as conservatives at the Philadelphia Society, an organization for conservative discussion Meyer helped found in 1964. When the father of fusionism died in April 1972, after converting to Roman Catholicism, many saw in his conversion “the great symbolic reconciliation, the ultimate fusion.”

Allow me to quibble with these efforts to identify conservatism with a fusionist vital center. A critical difference exists between an intense political engagement and the laying out of an ideological position.

Mind you, I’m not disparaging the importance of trying to persuade a political group that one hopes to influence. But such an activity is usually not of the same magnitude as a more life-consuming, let alone life-endangering, mission. Trying to sell a fusionist doctrine is not like staking one’s life for a cause. This endeavor is not the existential equivalent of what Ukrainians, who are fighting under siege to preserve their independence, are now doing; nor is it similar to the risky undertaking of those American colonists who declared independence from the British Crown. Although proposing one’s consensus position to a divided political group, may be noteworthy, it falls well short of an existentially defining mission. To restate Carl Schmitt’s deservedly famous distinction, we are speaking in this case not about the “political” as a life and death engagement but about a far less consequential activity.

Allow me then to make a further point: Sharing slogans or stating similar views at an annual conference—however exhilarating that experience may be—is not the same as struggling to save an inherited way of life. Hungarian-German sociologist Karl Mannheim defined “conservative thought” as precisely that, the fashioning of a worldview related to an existing social situation. Conservative thinkers, like Burke and his continental counterparts, were neither designing slogans for political campaigns nor drawing up unity statements for their colleagues. They were rallying to a way of life that was under attack, an agrarian hierarchical one they intended to preserve.

This articulation of a worldview which results from a defense of a threatened way of life seems to me an essential aspect of conservatism, historically understood. Meyer’s manifesto was designed to unite his fellow intellectuals in a polemical campaign against the Soviet Union. Whatever its merits, this statement of fusionism does not rise to the historic importance of Burke’s Reflections or Maistre’s Considerations on France. Meyer’s book is a document among other documents telling us about the internal disputes besetting the American conservative movement at a particular time. Thus, I would contextualize Meyer’s endeavor as one trying to find common ground for his fellow conservatives even as their movement was attempting to define itself.

Although well worth studying, that movement never acquired the large social base of an older conservatism, such as the one that mobilized followers against the “ideas” of the French Revolution. That crusade gave rise to a conservatism that lasted throughout most of the 19th century. It was socially situated, something our populist right has recently tried to become. This populist right that is still taking shape could become a political game-changer. Its protests even now are signaling more of a revolt against the leftist ruling class than all the recent editorials in the Wall Street Journal about what new or old faces are admitted to conservatism, inc. This populist upsurge (and I’m saying this with more than a tinge of regret) may be historically more critical than even those learned disputations by founders of National Review, on whose every word I hung as a young man.

Not surprisingly, the anti-Communist alliance that Meyer and the fusionists hoped to forge took a strange historical turn. What became the dominant force in that movement by the 1980s were the neoconservatives, who by then were well-placed advocates of an anti-Soviet foreign policy. On most issues, the new conservative leaders stood well to the left of Meyer and his critics of the 1960s. Arguably, Meyer’s fusionism ceased to be relevant as the neoconservatives imposed their own set of ideas on a changing movement.

Despite these twists and turns, self-described conservatives, many of whom worked for the administrative state or as lobbyists, continued to attend the same yearly conferences. But I doubt they were there because of an existential commitment or an intensely shared worldview. From what I recall, these attendees were networking professionally or else attended the meetings with their friends the way Englishmen of an earlier era went “to the club.” Those who came to these gatherings were motivated up to a point, but they in no way reminded me of Alexander Solzhenitsyn or of another spiritually driven anti-Communist, Whittaker Chambers, whom Dan McCarthy graphically depicted for The American Mind. The conference-enthusiasts whom I remember mostly lacked the fighting spirit that Frank Meyer so richly embodied. Lastly, I should stress that nothing I have said is intended to demean the founder of fusionism, who is someone I deeply respect and of whom, as a graduate student, I stood in awe. As a writer and speaker, I have always emulated Frank Meyer’s contentious style, even when I disagreed with him. As an historian of political movements, however, I have tried to put fusionism into historical perspective. Others are free to, and I would expect them to, dispute my judgments.

Image: Paul Gottfried speaking at the National Conservatism Conference in Miami, on Sept. 13, 2022 (National Conservatism YouTube page).

Leave a Reply