From the October 1990 issue of Chronicles.

F.A. Hayek, in The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism, offers us one insight into the nature of freedom and morality. Hayek argues that the major world religions have succeeded and endured because they reinforce the weak and imperfect points of human nature. Hayek believes that civilization is based on the family and on private property, institutions that Judaism and Christianity, in particular, have strongly emphasized. The question that Hayek should have raised, but did not, was that of the relationship between the high civilization of wealth and culture in Western Europe and America, and Western Christianity. Since the success of wealth-creation and freedom has occurred only in the areas of the world where Western Christianity gained acceptance, it is important to attempt to determine what special characteristics of Western Christianity contributed to this unique development.

The interdependence of religion and family in Western cultures was first explored by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges in his work The Ancient City, and while there have been many challenges to Fustel’s arguments and methods, his central insight retains its significance. Fustel found that certain traditions of Indo-European culture took strong root and flourished among the Western Indo-Europeans—the Greeks, Romans, Celts, and Germans. Among those societies, the role of religion was paramount. Religion was first and foremost the exclusive prerogative of the family. Each family formed its own religion. Each family saw itself as protected by the deceased ancestors who had gone to the afterlife. Each family formed a church.

The father and mother of the family formed the priesthood, which was exercised by the father. The father could perform his priestly functions only during the lifetime of his wife, because the priesthood was incomplete without the mother. After her death the priesthood then passed to the oldest married son and his wife. Obviously, a culture in which the wife was an integral and necessary part of the priesthood had a high regard for women.

Central to the concept of each family as an independent religious unit was the property on which the family practiced the family religion. The property was the location of the liturgy of the family religion and as such was sacred. Especially sacred were the family burial grounds. The property of each family had a religious significance and it was sacrilege for anyone outside the family to violate its clearly defined borders. All of this is reflected in Indo-European law, and especially the law of the Greeks and Romans.

The Greco-Roman world was not isolated and had to face the challenges posed by several religions of the eastern Mediterranean. Of all the religions from the East competing for the attention of the Romans, Christianity was the most demanding and required the greatest sacrifices by demanding strict moral standards for its converts. Despite state disapproval and sporadic persecutions, more and more people converted to Christianity. After Constantine and his successors adopted it as their personal and official religion, Christianity spread throughout the Roman world and even a bit beyond. Thus, on the Indo-European foundation of the sanctity of property and of the family, found in Greek, Roman, and German cultures, there was added the formal institutions and the precepts of Christianity. For fifteen hundred years the sanctity of property and of the family permitted the emergence in the West of the greatest contributions of culture and the widest diffusion of wealth in the history of the world.

In The Origins of English Individualism, Alan Macfarlane recounts the close connection in medieval English history of the development of the nuclear family and private property. This connection provides a crucial explanation of the rise of English culture and wealth, and the tradition made up of the nuclear family, private property, and individualism culminated in England’s American colonies.

Unlike the nations of the Continent, England and America have maintained what was historically the legal system of the European countries: the folk-law or common law. The common law is rooted in Indo-European history and still reflects its original precepts. In the early modern era, other European countries saw their original legal systems replaced by a statist civil law system based on Roman imperial edicts. The change in continental legal systems was part of a larger strategy to create the Total State, an effort to enhance the power of the state against society and the institutions that comprise society: private property, the family, the church.

To create the modern fiscal state, the Total State, it has been necessary to fracture the institutions that stood between the state and the property it coveted—the institutions of the family and religion. In various ways, the family and religion were directly or indirectly undermined. Resistance arose all over Europe, but only in England, and then in America, was this resistance successful.

The Englishman’s resistance to the modern fiscal state is the history of liberty, as Lord Acton described it. Rooted in the Puritan culture of England, the resistance to the Total State achieved success after a series of organized resistances. During the reigns of James I and Charles I the struggle became more and more intense, until in the English Civil War the king was executed and a republic declared. But the Commonwealth and the Protectorate of Cromwell moved in the direction of the modern fiscal state, and to avoid the Total State, the dead king’s son was restored to the throne, but with greatly reduced powers. When Charles II’s brother, James II, sought to expand those powers, he was exiled and his daughters succeeded him—Mary (with William) and Anne. The Revolution of 1688 with its Bill of Rights was not only of the greatest importance for England but for America as well. The defeat of the modern fiscal-state meant the protection of private property and the institutions that gave it strength—the family and religion.

The sanctity of private property in Western society was rooted in the family religion that was universalized by Christianity. The institutions of religiously-based family and property provided the material as well as the spiritual bases of Europe’s and America’s culture and prosperity. In The History of the Idea of Progress (1980), Robert Nisbet describes the importance of Christian doctrine in the emergence of the idea of progress: “A very real philosophy of human progress appears almost from the very beginning in Christian theology, a philosophy stretching from St. Augustine (indeed his predecessors, Eusebius and Tertullian) down through the seventeenth century.”

Throughout the Middle Ages science was an important part of the studies of the Schoolmen. Progress in knowledge and in mankind’s prosperity went hand in hand. This scientific focus laid the foundations both for the scientific discoveries of the early modern period and “the idea of progress.” As Nisbet observes:

The fundamental structure of the idea, its governing assumptions and premises, its crucial elements—cumulative growth, continuity in time, necessity, the unfolding of potentiality, all of these and others—took shape in the West within the Christian tradition. The secular forms in which we find the idea of progress from the late seventeenth century on in Europe are inconceivable in the historical sense apart from their Christian roots.

The religious foundation in Christianity of the concepts of growth and development were rooted in the sanctity of private property and the family. This sanctity gave growth, development, and accumulation both certainty and meaning. The actual growth, development, and change in the culture and industrialization of the West was possible due to the idea of progress, which was rooted in Christianity.

The scientific discoveries and technological development that occurred in England in the 17th and 18th centuries—the scientific revolution and the Industrial Revolution—were rooted in the ChrisHan tradition and expressed themselves in a society that still maintained the Christian-based institutions of private property and family. The resistance to the modern fiscal state gave England the ability and freedom to pursue development and progress, and to expect the fruits thereof to remain the property of the family and not of the Total State.

The American Revolution was the most important of the movements of resistance to the Total State. The revolutionary foundation was the argument from a Higher Law than the statutes of the state. The American Revolution represented a landmark in the more than two-thousand-year tradition of natural law.

Dr. F.A. Harper, founder of the Institute for Humane Studies, in “Morals and Liberty” (1971), underlines the freedom to choose as an essential part of moral frameworks.

This view—that there exists a Natural Law which rules over the affairs of human conduct—will be challenged by some who point out that man possesses the capacity for choice, that man’s activity reflects a quality lacking in the chemistry of a stone and in the physical principle of the lever. But this trait of man—this capacity for choice—does not release him from the rule of cause and effect, which he can neither veto nor alter. What the capacity for choice means, instead, is that he is thereby enabled, by his own choice, to act either wisely or unwisely—that is, in either accord or discord with the truths of Natural Law. But once he has made his choice, the inviolate rule of cause and consequence takes over with an iron hand of justice, and delivers unto the doer either a reward or a penalty, as the consequence of his choice. . . .

If I surrender my freedom of choice to a ruler—by vote or otherwise—I am still subject to the superior rule of Natural Law. Although I am subservient to the ruler who orders me to violate Truth, I must still pay the penalty for the evil or foolish acts in which I engage at his command.

Christian doctrine calls attention to Original Sin, which has clouded Man’s will. Otherwise our choices would be easy, not hard. It is our clouded will that has made the attainment of the good, the understanding of the good, and the selecting of the appropriate good among several seeming goods, so difficult. What is appropriate or good in one context can be evil or lead to evil in another context. For example, mankind’s sexual appetite, like our other appetites, was endowed in us by God for an important and appropriate purpose. Individuals or groups who pursued sexuality outside of marriage and the family suffered and continue to suffer the evil consequences of pursuing an apparent good without the institutional guidance of the family structure.

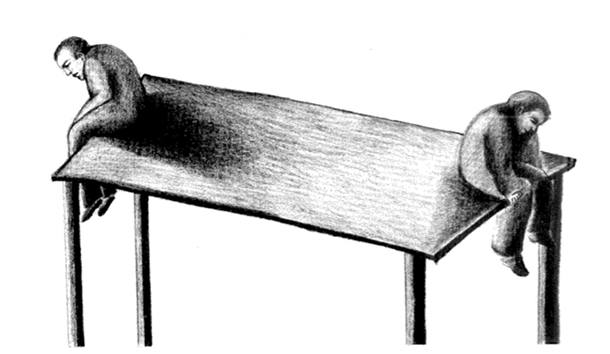

Similarly, the tenderness and sharing that are essential parts of the family cannot be generalized outside the family structure. The attempt to treat the whole society—city, county, state, or nation—as a family and enforce the affections that are appropriate to the family, and only appropriate within a family, can only corrupt and confuse society.

We can see in our society the consequences of separating—by legislating an artificial family, a mass extended family—tenderness and sharing from the direct training and education of children. Those who receive what the government takes from others are subjected to the commissioners of sharing and of tenderness as their children are subjected to the boards of training and education. We have the necessary separation and specialization of bureaucracies that do not connect development in education with tenderness and sharing. The family is the premier example of an interdisciplinary, nonspecialized institution. The success of the family over the ten thousand years of man’s recorded history is one of the most important sources of lessons for our society.

American society is suffering the consequences of the separation of responsibility from individual family decisions. Freedom and morality as natural entities are not able to function when responsibility is diluted or removed. Freedom and morality cannot complement each other when responsibility is eliminated. Our society suffers its current crises as a result of abandoning the social foundations on which its previous successes were built.

Every choice we make has consequences for us. We must bear the burdens of our choices. If our choices are irresponsible we suffer the consequences and learn from them. We change our choices by reforming. We reform ourselves each day in small ways that in most people eliminates the need for drastic change. Governmental institutions, on the other hand, freeze decisions and make incremental reforms almost impossible. This creates the demand for drastic results. Removing more decisions from governmental institutions will make it possible to achieve necessary reforms in an easy rather than difficult manner. The natural relationship between freedom and morality, then, can be restored to its appropriate harmony.

Leave a Reply