The most telling moment in The Agenda, Bob Woodward’s book on the Clinton presidency, occurs when the President-elect first realizes that Wall Street’s bond markets wield more power than he does as Commander in Chief of the lone remaining superpower. “You mean to tell me,” Bill Clinton screamed at his aides, his face turning red with anger and disbelief, “that the success of the program and my re-election hinges on the Federal Reserve and a bunch of f—ing bond traders?” Woodward does not say whether Clinton acted on his campaign promise to lower interest rates by going long on the 30-year U.S. Treasury bond for his own account. Presumably not; Hillary, after all, is the rainmaker in the Clinton family.

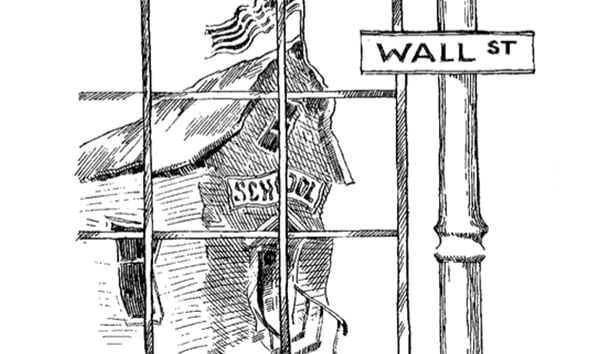

The subtext of Woodward’s book is that the bond market and the Federal Reserve, in the form of Chairman Alan Greenspan, hold the real power. As the 21st century unfolds, all roads lead to Wall Street, even those associated with American education. Neoconservative policy wonks may fantasize about privatizing the little red school house or propose a “school choice” utopia that resembles nothing so much as the liberal dream of busing. But these think tank schemes, funded by non-profit foundations, are a sideshow; increasingly, the public education agenda is developed by corporations and implemented by politicians who need their campaign contributions.

The public education lobby is stronger, and more broadly based, than many of its critics realize. It includes not only familiar neoconservative bogeys such as the teachers’ union, but corporations that support scams such as those found in the George Bush-created Goals 2000 (like School-to-Work and Outcome-Based Education). Neoconservative mythology holds that the only bulwark against this state of affairs is the Republican politician. But in the real world, these politicians do not wield the real power.

Bush wanted to be known as “the Education President,” and so does his successor. “Our number one priority,” Clinton told the Michigan legislature last year, “must be to make our system of public education the best in the world.” Clinton was invited to Lansing by Republican Governor John Engler, whose property tax cut/school finance plan, called Proposal A and passed by voters in 1994, is seen as a national model by, among others, the New York Times and National Review. “No challenge confronting our state or the nation is more urgent,” Governor Engler told Clinton and lawmakers. “Where our children are concerned, our search is not strictly for a Republican solution or a Democratic solution—but an American solution.”

Governor Engler invited Clinton to Michigan because the two agree on education. In 1994, Clinton signed the School- To-Work Opportunities Act, which uses federal mandates and funding to browbeat public schools into changing their mission. Education’s traditional function is to teach basic knowledge and skills: reading, writing, and arithmetic. School-to-Work de-emphasizes academic work and substitutes mandated vocational training to serve the corporate workforce. “The goal is not to graduate highly literate individuals but to turn out team workers to produce for the global economy,” notes Phyllis Schlafly.

In the school-to-work scheme, individual grades are inflated or detached from academic achievement, individual honors and competition are eliminated or de-emphasized, and instead we have such “team” techniques as group grading, cooperative learning, peer tutoring, horizontal enrichment, job shadowing, mentoring and job site visits.

School-to-Work is administered in Michigan by the state Department of Jobs Commission, dubbed the “Corporate Welfare Department” by critics. The line-item for fiscal year 1998-99 is $10.9 million; more than $50 million has been spent on School-to-Work since the program’s establishment. The appropriations boilerplate for the program reads, “The school-to-work apprenticeship programs shall link employers, organized labor, educators and community organizations for the purpose of providing necessary knowledge, skills and labor market information to students.” Translation: state government will tell students which jobs are available and taxpayers will pay to train them for politically connected corporations. In this incestuous relationship. Big Government climbs into bed with Big Business and Big Labor, two-timing the taxpayer.

Growth in the School-to-Work program mirrors growth in the Corporate Welfare budget. The executive order creating the Jobs Commission was signed by Governor Engler in February 1993. “[I]t is vitally important that there be maximum coordination, accountability and performance-related measures with respect to programs to foster economic expansion and workforce development [emphasis added],” the order reads. “[I]t is also vitally important that the Governor develop policies, make and implement legislative proposals, and consolidate and implement programs to foster economic expansion in the State of Michigan.” The American Heritage dictionary defines “foster” as to bring up, nourish, or feed. Taxpayers are feeding the Corporate Welfare Department today to the tune of $602.25 million, an increase of more than 140 percent since Governor Engler signed his executive order. Politically connected corporations have applauded the Corporate Welfare Department: they receive the benefits, paid for by taxpayers, of programs like School-to-Work. More than $2.25 billion has been spent by the Jobs Commission since 1994.

“Michigan does not need a government-directed industrial policy; it needs leadership that understands and respects the operation of a free market economy,” the Mackinac Center for Public Policy argues in a recent publication, Advancing Civil Society: A State Budget To Strengthen Michigan Culture. “Instead of focusing on expanding so-called ‘pro-business’ programs, the governor and legislature should recognize the institutions . . . that generated tremendous wealth in Michigan long before the advent of pervasive government intervention.”

The corporate welfare lobby aggressively supported passage of Proposal A. Powerful in Engler’s Michigan, its power is greatly reduced on Wall Street, where the bond market rules. The neoconservative dream of Michigan’s Proposal A as a national model for school finance is still subject to the bond market’s cold, hard judgment.

While Wall Street may have its doubts, others in New York like Proposal A. The New York Times called it

the first statewide, voluntary shift away from property taxes, as a rising national chorus of disgruntled homeowners and civil rights activists seek more equitable ways to provide one of society’s most basic services. Education in America has traditionally been seen as a local concern. Hence the reliance on property taxes, which are also less vulnerable to economic fluctuations, to finance school systems. But property assessments within and among states diverge wildly. Across the country, the amounts of money spent on schools based on the taxes derived from those assessments are unconscionably unequal. . . . Now 28 states are involved in lawsuits, many based on state constitutional promises of fairness, that seek to redistribute school aid. . . . Throughout most of the U.S., children in wealthier school districts continue to benefit from superior education while those who live in poorer districts—and who need more resources, not fewer—continue to be deprived. . . . The fact that Michigan voters have . . . tried to make school financing fairer should make other states sit up and take notice.

Put bluntly, the New York Times praised Proposal A’s egalitarianism: it centralizes power in Lansing and redistributes tax dollars from upscale suburban districts to poorer urban schools. But the Times’ “voluntary shift” was anything but. Proposal A gave voters the option to raise the income or sales tax to six percent. They could not reject both: a vote against the sales tax increase would have raised the income tax. Taxpayers likened this to a choice between shooting oneself in the head or shooting oneself in the heart. The opportunity to reject any tax hike was taken away by Lansing after voters defeated a different proposal in June 1993.

Governor Engler was elected in 1990, upsetting incumbent Democrat James Blanchard; his platform pledged property tax relief His first tax cut plan was rejected by voters in November 1992. After his second one failed in June 1993, Engler was anxious to cut property taxes before the 1994 election. Writing in National Review, Northwestern University Law Professor Daniel D. Polsby praised Governor Engler as “a gambling man.”

In the summer of 1993, Democrats, in a ploy to illustrate the supposed intellectual bankruptcy of Mr. Engler’s plans, pushed a proposal through the state House of Representatives that would simply abolish school funding through property taxes. Mr. Engler did not blink. He got the state’s Republican-dominated Senate to pass the measure too, and then he signed it. And so, in July of 1993, Michigan enacted into law a $6.6 billion deficit in its public school budget, effective as of July 1, 1994, with absolutely no substitute funding provided for. An historic opportunity to rethink the system, said Mr. Engler. Bystanders likened it to jumping off a diving board without first checking to see whether there was water in the pool. Under the gun, the state acted, jacking up the sales tax and cigarette taxes to cover the funding shortfall.

But the National Review account erred: it was not the state House that created the crisis but the Republican-controlled Senate; the amendment abolishing property taxes was sponsored by Senator Debbie Stabenow (Democrat-Lansing), now a member of Congress. After ending property taxes, the legislature partially restored them amid a crisis that ended in a marathon 26-hour session on Christmas Eve 1993. In addition to raising the sales and cigarette taxes, as Polsby reported, the deal forced voters to raise user fees and utility and real estate transfer taxes when they approved Proposal A on March 15, 1994.

Beware the Ides of March, critics warned. But Michigan voters accepted Proposal A’s tradeoff: a property tax cut coupled with a sales tax increase. State Treasurer Doug Roberts proudly notes that Michigan now ranks 38th nationwide in terms of state and local tax burden as a percentage of personal income. In 1993, prior to Proposal A’s passage, the state ranked 15th, according to the U.S. Department of Census. Once considered a high-tax state, Michigan’s tax burden is now around the national average. Economists say the state could do better, but Governor Engler deserves much credit; he has signed 24 tax cuts into law in eight years. “But the upshot of this political melodrama has not been without controversy,” Polsby wrote in National Review. “If property taxes were cut, the potential for central control of education from Lansing was increased.” Local school officials complain that state officials are deaf to this concern. In an ironic twist, state officials have their own complaint about centralized power: the repeated refusal of Wall Street bond-rating agencies to upgrade Michigan’s debt to AAA since Proposal A’s passage.

Wall Street, however, has liked much of what it has seen out of Michigan lately. In January 1998, Standard & Poor’s upgraded Michigan’s debt to AA+. Moody’s followed suit in March, raising Michigan’s rating to Aal. Both upgrades represent an improvement from January 1991, when Governor Engler took office. S&P placed Michigan on a “credit watch” that month, noting a budget deficit (since eliminated) left over from the Blanchard years. But both upgrades included cautionary notes. Michigan’s strengths, S&P noted, “are mitigated by decreased revenue flexibility and increased funding commitments related to the implementation of school funding reform” and the cyclical nature of the state’s automobile industry. “Debt factors are favorable,” Moody’s reported.

However, contingent debt issued through the School Bond Loan Fund program . . . continues to grow rapidly and is outstanding in amounts that nearly double direct state debt. Continued careful management of this contingent debt exposure, particularly in the state’s financially weakest school districts, such as Detroit . . . will be important to the stability of the rating.

Proposal A addressed the operational side of school finance—the inequities between rich and poor school districts— but it left unresolved the issue of debt. “We have not had a debate on this issue since the 1970’s,” said Nick Khouri, vice president of Public Sector Consultants, a Lansing group, and deputy state treasurer when Proposal A was written. Echoing Wall Street, Khouri notes that the School Bond Loan Fund “has exploded in recent years, increasing the cost to the (Michigan) budget and creating a potential long-term financial liability for state taxpayers.” One of the reasons Khouri cites for “the dramatic increase in school debt” is Proposal A, which “lowered the average homeowner’s millage rate for school operating purposes from 35 mills to six. This sharp drop was seen by many school administrators as an opportunity to ask voters to replace part of the reduction with an increase in debt mills.”

State Treasurer Roberts concedes Proposal A did not solve the debt issue. In fairness to Roberts, there probably would not have been enough votes to pass a better plan. Half of the Republican legislative caucus—and most of the Democrats—would have resisted a solution. But Governor Engler and Roberts have failed to convince Wall Street to give Michigan a Aaa/AAA credit rating—despite repeated attempts. Wall Street is watching how Engler’s administration solves a crisis unraveling in the Detroit school district, where taxpayers approved a $1.5 billion school bond issue in 1994. Roberts will not approve the bonds because Detroit officials have not provided a good explanation of how the district spent the money from an earlier $162 million bond project. Prosecutors last year declined to pursue criminal charges in the affair because they could not determine whether any Detroit officials personally profited from the deal. The decision not to prosecute ended a 20-month joint FBI and state police criminal probe.

The most likely solution to this problem is not political, but financial: debt restructuring, or better yet, shock therapy—an economic czar to clean up the Detroit mess. For Proposal A to emerge as the national model for school finance, the debt side of the issue must be addressed in a manner that will be approved by the bond market.

“How many votes does the f—ing bond market have?” complains Howard Paster, a Clinton lobbyist, in Bob Woodward’s The Agenda. More power than hack staffers like Paster will ever admit.

Leave a Reply