Although it is easy for a superior power to occupy a densely populated hostile area, modern history teaches us that it is almost impossible to make that occupation militarily and morally viable or cost-effective in the long run. In composing the Treaty of Versailles the Allies, led by France, imposed huge reparations on Germany. They were an unbearable burden for the Weimar Republic, which stopped its payments in 1922. France, with Belgian assistance, responded in January 1923 by occupying the Ruhr, Germany’s main coal and steel producing region. Raymond Poincaré, France’s premier, declared before the Chamber that coal would be requisitioned as payment in kind.

The operation lasted until August 1925 and it was an utter failure. It encountered passive resistance, civil disobedience, and acts of sabotage by German civilians—130 of whom were killed by the occupying soldiers. Facing economic and international pressure, in August 1925 France and Belgium withdrew their troops without having obtained even a fraction of the expected revenue. Quite the contrary, the occupation of the Ruhr contributed to the growth of radical nationalism in Germany. This helped Hitler come to power a decade later, with tragic consequences for both France and Belgium in the summer of 1940.

Even amid hyperinflation and foreign occupation, the Ruhr 100 years ago seems like paradise compared to Gaza today. Some pertinent parallels nevertheless are worth noting. Keeping a hostile civilian population under control is a major challenge for the occupying power, especially an occupier that states upfront it has no intention to annex the territory in question (as was obviously the case with the United States in Afghanistan). When all sides know that the occupation is temporary, the spirit of resistance is easier to kindle. Any regime change instituted by the occupying power is seen as transient—and in any event Israel cannot hope to find any cooperative Gazans who don’t want to die a gruesome death within hours.

It is of course possible for the occupying power to proceed with a massive campaign of ethnic cleansing, of the staggering magnitude which Poland carried out in Silesia, West Prussia, and Pomerania in the spring of 1945. That was possible, however, only because Germany was utterly defeated and considered worthy of collective punishment by the victors.

The logistics of displacing over a million people and squeezing them into an even smaller open prison in the southern part of the Gaza strip theoretically can be worked out. It would be an extremely messy and ugly business. Israel cannot do it without incurring massive odium in many hitherto sympathetic or at least neutral quarters (especially in Europe and India). It is noteworthy that just as most of “the Global South” condemns the war in Ukraine but does not participate in the economic war against Russia, most of those countries now condemn the attack by Hamas but demand a containment of violence and the revival of the two-state solution. In addition, Israel cannot unleash its fury on Gaza without helping forge an Arab and Islamic front more solid and hostile to the Jewish state than anything seen since 1948, and above all without jeopardizing its vitally important standing in the United States.

This scenario needs to be considered, however, because the Arab street and the Islamic world as a whole are abuzz with the claim that Israel allowed the “surprise attack” of Oct. 7 (they call it “prison break”) to take place in order to provide themselves with an excuse to destroy Gaza. Such speculation is further fueled by the credible Egyptian claim that it had warned Israel of the impending attack some days before it happened.

As we await the much-heralded start of the ground operation in Gaza, Israel faces an awkward strategic dilemma. It needs to restore the credibility of its ability to protect the lives of its citizens in general and the reputation of its military and intelligence apparatus in particular. To that end, hitting back at Hamas effectively and ferociously is considered a must. The backbone of Hamas cannot be broken by aerial bombardment alone, however, especially since the intensity of Israeli air attacks is always directly proportionate to the Palestinian civilian casualties. Any Israeli claim that the civilians had it coming because they had not evacuated Gaza City as ordered by the Israeli Defense Forces is certain to be universally derided because the order was objectively impossible to obey.

On the other hand, entering Gaza with ground forces means engaging in the most challenging and potentially the costliest type of tactical fighting: urban warfare. Think Stalingrad, think Algiers, think Grozny. To eradicate Hamas, Israeli forces would need to fight their way through the rubble street by street, building by building, like the Russians did at a great cost in Mariupol last year. They would need to locate and neutralize an intricate network of tunnels, some of them 200 feet deep—a feat which U.S. forces found to be particularly daunting in Vietnam. They would need to reach the sea and establish a security perimeter facing the southern half of the enclave. They would have to comb the city of Gaza, which Hamas fighters know inside out and in which they have worked out various techniques of ambushing Israeli patrols and vehicles. Apartment block cellars have been turned into bunkers, narrow alleyways into death traps.

To win, Israel must destroy Hamas utterly and permanently, or at least for a period of 10 to 15 years—a very tall order. For Hamas, victory means making the Israeli incursion very costly, avoiding eradication, and surviving to fight another day. Regrouping and recruiting new members to replace the fallen after the Israeli withdrawal will be easy, with tens of thousands of angry young Palestinian men, with no work and no prospects, itching to join the struggle. Israel can never truly win, because even if it had the means for the complete destruction of Hamas, it would not be able destroy the ideology that gave it life—which the violence of revenge would only help to spread and intensify.

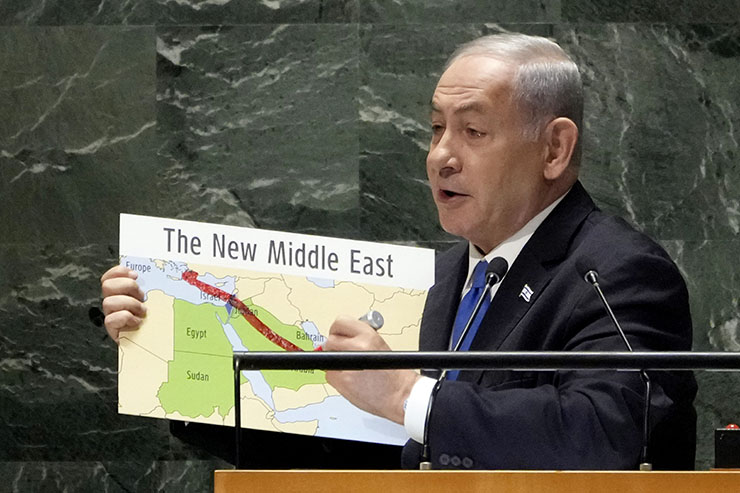

The nightmare of urban warfare in Gaza would be exactly what Hamas wants: a costly imbroglio for the IDF, and an almost limitless potential for atrocity management by using civilians as human shields. It would result in a political fallout which would permanently destroy any chance Israel might have had of normalizing relations with the Arab world. It would return the Palestinian issue to the regional agenda, which had been the strategic objective of Hamas all along. Saudi Arabia has suspended talks with Israel. Much to the chagrin of the Biden administration, the agreement mediated by China last spring, which helped rebuild relations between Iran and the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf, is now helping create a common Sunni-Shiite position vis-à-vis Israel.

An additional problem which Israel faces after Oct. 7 is that thousands of Jews all over the world who may have considered aliyah (immigrating to Israel) will now think twice. This is a little known but tangible consequence of the horrid scenes in Sderot and elsewhere: immigration into Israel will decline.

It is very hard to determine what a victorious Israeli ground campaign in Gaza would look like. Without a clearly defined political objective—without “victory” being defined—it should not be launched. It is better to refrain from retribution (Netanyahu’s term), probably at a great cost and to no good purpose, than to do exactly what Hamas wants Israel to do.

Hamas does not want Israel to exercise prudence and refrain from entering Gaza, while keeping the strip under vigilant guard. Hamas wants the carnage in Gaza to prompt the opening of the second front with Hezbollah along Israel’s border with Lebanon. It wants fresh turmoil in the West Bank, where tensions between Jewish settlers and Palestinians are rapidly rising. Iranian militias remain ready in Syria, and Israeli air strikes on the airports of Aleppo and Damascus suggest that the Iranians are airlifting fighters and weapons to strengthen their capabilities there.

Instead of facing a war on the four fronts of Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and Syria—and ruining the prospects of mutually advantageous détente with the Arab world in the process—Israel should return to its usual state of permanent vigilance along the border and refrain from obliging its enemies. After Varus lost three legions east of the Rhine in A.D. 9, Rome still rose to unprecedented power and glory which lasted for centuries, even though it never again tried to conquer Germania.

Far from being a sign of weakness, restraint can be strategically sound and politically profitable. Israel could also leave open the possibility of restarting the peace process with the Palestinian National Authority and the rest of the Arab world. The final political objective should be clear: to establish an internationally recognized Palestinian state which would recognize Israel’s right to exist. Only in this way can Palestinians be given a real alternative to Hamas’s agenda.

Leave a Reply