What one man in America can decide that prisoners in South Carolina need croquet fields and backgammon tournaments and order the state to provide them? What one man can decide that Kansas City schools need Olympic-size swimming pools, a planetarium, a model United Nations wired for language translations, a temperature-controlled art gallery, and movie editing and screening rooms, then issue $500 million in bonds to pay for them and double Kansas City real-estate taxes to pay for the bonds? If you answered, “a federal judge”—you are right.

The power wielded by these judges has provoked some remarkably frank criticisms of the judiciary. Federal judges are a “robed, contemptuous intellectual elite,” according to Republican Senator John Ashcroft of Missouri. Ashcroft, chairman of a Senate Judiciary subcommittee, said he would hold hearings to examine situations “where the people’s will has been set aside by the courts” and to design checks on activist judges. Representative Tom Delay of Texas wants to impeach judges who are “arrogantly overriding the people’s will.” These judges, he notes, have overturned referendums—dealing with immigration costs, affirmative action, homosexual preferences, and school busing—adopted by the people of California, Colorado, and Washington. Is Senator Ashcroft right? Have federal judges really become a threat to popular government?

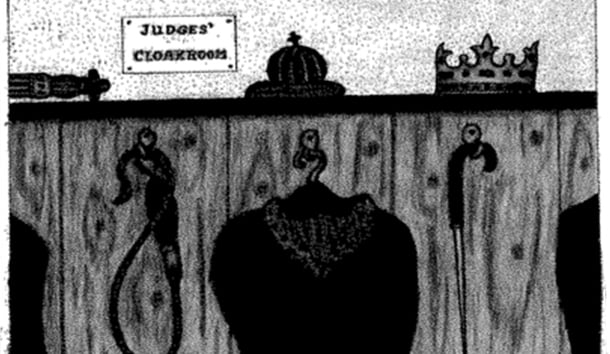

Judicial taxation is a recent and extreme form of the judiciary’s takeover of traditional state functions. But it is also a symptom of an even deeper problem—the virtually unlimited discretion of a federal judge to control public officials, and, in so doing, consolidate in himself all the functions traditionally performed by an entire government. The judge exercises the power to tax and spend in the manner of a legislature and then hires special masters with large staffs to execute his wishes in the manner of an executive. Is one man supposed to have that kind of power? Montesquieu said “virtue itself has need of limits” and that it “is necessary from the very nature of things that power should be a check to power.” One wonders what Montesquieu would think of the following:

1. The Supreme Court, in its 1990 Jenkins decision (ordering new taxes to finance Kansas City magnet schools as part of a desegregation plan), found that a “court order directing a local government body to levy its own taxes is plainly a judicial act within the power of a federal court.” Magnet schools are public schools of voluntary enrollment designed to promote integration by drawing students away from their neighborhood and private schools through distinctive curriculums of a high quality. The Supreme Court believes that a federal judge must be able to right any wrong he sees. Righting the wrong in this case apparently meant high schools in which every classroom will have air conditioning, an alarm system, and 15 microcomputers; a 2,000-square-foot planetarium; greenhouses and vivariums; a 25-acre farm with an air-conditioned meeting room for 104 people; a model United Nations wired for language translation; broadcast capable radio and television studios with editing and animation labs; a temperature-controlled art gallery; movie editing and screening rooms; a 3,500-square-foot dust-free diesel mechanics room; 1,875-square-foot elementary school animal rooms for use in a zoo project; and Olympic-size swimming pools. By 1995, the total cost of these judicially ordered improvements had soared to over $540 million. Desegregation costs have escalated and now are approaching an annual cost of $200 million. In Kansas City, “white flight” long ago emptied the city of middle-class homeowners, so the tax burden is predominantly paid by businesses who pass it along if they can.

2. Rockford, Illinois, is an old industrial city with plenty of remaining blue-collar and white-collar, middle-class homeowners. Putatively to avoid protracted legal fees, Rockford’s school board did not contest a racial discrimination lawsuit. That was a mistake. A federal magistrate and his handpicked desegregation “master” set to work designing a new school system for the city. By the end of 1996, the magistrate had ordered $150 million in new property taxes. Rockford homeowners—who have lost control of their destiny—are furious.

3. Judicial taxation is taxation without representation, and that makes people angry. However, if a city council should resist and refuse to pass judicially ordered legislation, a federal judge can bankrupt the city. The Supreme Court, in the 1990 Yonkers case, approved contempt penalties of $1 million per day against the city until the council voted to place the public housing where the Court wanted it.

4. The Supreme Court, for more than 20 years, has authorized its district courts to use “equitable remedies” to undertake legislative and executive functions. The Court made this broad grant of authority in the 1968 Green v. New Kent County decision, which found that Virginia had an affirmative duty to integrate its school system pursuant to court-approved plans. Based on this decision, the federal courts have assumed control not only of schools but of prisons, mental hospitals, and public housing.

5. Judicial taxation does not seem analitically distinct from any of the other federal mandates which shape a state’s spending power. In South Carolina, for example, a federal judge, pursuant to a consent decree, ordered prisons built and maintained at a level of comfort established by the ACLU Prison Project, which included croquet fields and backgammon tournaments. The judge did not order new taxes, but the effect is the same since the state budget must, to avoid a tax increase, be cut elsewhere (e.g., the state must reduce public school funds to provide court-ordered education for prisoners).

The Court, in the examples above, combines the judicial, legislative, and executive powers into a single person, but does it really have the authority to do so? To answer this question, we have to go back to the basics. “The ultimate question,” Learned Hand wrote in 1958, “is whether the rights of individuals are safer in the hands of the majority than in the hands of appointed guardians.” Hand believed a free society “will find its own solutions more successfully if it is not constricted by judicial intervention.”

“If men were angels,” James Madison wrote, “no government would be necessary,” and “if angels were to govern men, no controls on government would be necessary.” Lacking either condition, Madison assumed that we need checks and balances to limit power. Thomas Jefferson wondered if “man cannot be trusted with the government of himself, [can] he, then, be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels in the forms of kings to govern him?” Is it plausible, is it likely, that the Founders threw out an English king so they could be ruled by nine judges on a Supreme Court?

Chief Justice John Marshall in Marbury v. Madison (1803) asserted that his Court was the final authority on what the Constitution says. Because of Marshall, the guardians appointed to the Supreme Court have the last word on most of the important cultural, social, political, and economic issues facing the country. Marshall’s theory of judicial review. Hand believed, was not supported by any language in the Constitution or in democratic philosophy. He thought judicial supremacy clearly violated the doctrine of the separation of powers, the centerpiece of our republic. Nonetheless, Hand thought judicial review should play a small role in a narrow group of cases to provide a final arbiter for clashes between the separate branches.

But the two ideas—majority rule and judicial supremacy— are, as Hand recognized, oil and water. The majority can rule or the guardians can rule, but they cannot both rule. Hand’s effort at reconciling them was to say that judicial review should only be used in extremis—it would be confined to the need that evoked it.

According to this doctrine of judicial restraint, the courts could only govern us in cases of absolute necessity. The country prospered under this doctrine into the 1950’s, but it depended on the cultural outlook of the individuals involved and their understanding that the independence of the judiciary would be lost if the limits of judicial power were not recognized. It was never an intellectually stable doctrine—it could not formulate a clear and valid criterion to describe when the Court would or would not intervene and govern. It was a self-imposed deference to the legislature with very elastic limits. But, despite its theoretical weakness, judicial restraint was very successful because it respected the constitutional obligations of the states and of the other two branches of government.

The current Court, for the most part, respects the constitutional obligations of the other two branches of government but not those of the states. The federal courts tell Kansas City and Rockford how to run and finance their schools; they do not tell Congress or the President how to perform their constitutional duties. The courts view the states as regional departments of the national government rather than the sovereign entities that won the Revolution and created the Constitution.

Thomas Jefferson wrote to William Giles on December 26, 1825, “it is but too evident that the three ruling branches of that department are in combination to strip their colleagues, the State authorities, of the power reserved to them, and to exercise themselves, all functions, foreign and domestic.” In other words, the separate national powers would naturally have more to gain by combining and cooperating than by clashing.

As Jefferson wrote in his Autobiography (1821), “Our federal judges are effectually independent of the nation.” Jefferson believed that, though honest men are appointed to the judiciary, “all know the influence of interest on the mind of man and how unconsciously his judgment is warped —how can we expect impartial decision between the General Government, of which they are themselves so eminent a part, and an individual state from which they have nothing to hope or fear.” The federal judges “are then, in fact, the corps of sappers and miners steadily working to undermine the independent rights of the States and to consolidate all power in the hands of that government in which they have so important a free-hold estate.” As he wrote to William Jarvis in 1820, “Our judges are as honest as other men, and not more so.”

Jefferson believed that majority rule should always prevail and that individual rights are safer with majority rule than in the hands of judicial guardians. He did not believe the Supreme Court had even the limited review power present in Hand’s doctrine of judicial restraint. He also did not believe the Constitution made the judiciary supreme over the other branches, or over the states. The Constitution instead delegated authority to each of the separate and coequal branches. The exercise of any delegated power presupposes that the grant extends to the occasion that has arisen, and it is a necessary incident of the grant itself that the grantee shall so decide before he acts. The grantee may, of course, be wrong, but then he is accountable to the grantor and no one else.

The President, under Jefferson’s approach, has a duty to execute only those statutes —and judicial orders—that he independently believes are constitutional, regardless of a Supreme Court decision to the contrary. The courts are supposed to enter such orders as they think proper and constitutional, but neither the President nor Congress, if they disagree, are bound to enforce them.

The Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in 1798, subjected friendly aliens to deportation and made it a crime to criticize the government or a government official. The federal courts upheld the constitutionality of the laws. Twenty-four people, mostly newspapermen, were seized and ten found guilty and jailed in a bloodless reign of terror. As soon as Jefferson became President in 1801, he exercised what he believed to be his constitutional duty and freed everyone jailed under the Alien and Sedition Acts, returned fines, and ended all prosecutions under them. He later wrote to Abigail Adams that the law was “a nullity as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image; and that it was as much my duty to arrest its execution in every stage as it would have been to have rescued from the fiery furnace those who should have been cast into it for refusing to worship the image.”

Under Jefferson’s approach, if the branches disagree, they need to work it out. For our system to work smoothly, the three branches have to be in agreement—the legislature passes the law and appropriates the money, the executive carries out the law, and the judiciary should base its rulings on the law. Usually, the disagreement arises between Congress and the Courts. The President, in such a case, could act as tie-breaker. Conceivably, the three branches could take three different positions, something which strikes us today as very disorderly—and it is. But Jefferson did not see disagreement as a bad thing—it is the way difficult problems get worked out in a democracy. And, as Dumas Malone has noted, Jefferson’s approach describes how our government actually worked until the eve of the Civil War.

Can Jefferson’s approach be resurrected? It is attractive because it does not require any new statute or constitutional amendment, just a different outlook. It is making progress at the state level. In Washington, Representative Kathy Lambert has proposed a Jeffersonian “Balance of Powers Restoration Act,” which would give the legislature power to review and overturn state supreme court decisions that invalidate acts of the legislature. The Governor could follow whichever opinion he agreed with until the people, in a referendum, make the final decision. At the national level, however, the Jefferson doctrine would probably only resurface if the Supreme Court is foolish enough to make a serious attack on presidential or congressional power—an unlikely scenario. As Jefferson noted, the natural expectation is that the Court will expand and enhance the powers of the other two national branches. And despite the complaints of some members of Congress, the other branches will not get into a fight with the Court over a state’s rights issue that does not concern their own powers.

Congress, the main beneficiary of the Court’s rulings, will never be serious about limiting the power of the Court. Indeed, Congress has successfully given the public the impression that, because of the separation of powers, it has no clear power over the federal courts. But the Constitution, in Article III, grants Congress almost absolute power over the judiciary. Congress created the lower courts in the first Judiciary Act and could abolish them tomorrow. Indeed, at the Constitutional Convention, a constitutionally mandated lower federal court system was debated and rejected. Congress also can withdraw the Supreme Court’s power to hear appeals in whole or in part. If Congress does that, the Court is limited to its enumerated “original” jurisdiction—cases involving ambassadors and those in which a state is a party. Although the Constitution places the Supreme Court at its mercy. Congress has chosen not to use its powers.

What about a new constitutional amendment to prohibit judicial taxation? Unfortunately, judicial taxation is a symptom of a much deeper problem, and it is that problem which needs to be solved. Moreover, it is unlikely that Congress, which will not let the states vote for an amendment on term limits or a balanced budget, will propose an amendment to limit judicial power over taxes. But even if an amendment were ratified, its wording would be, to quote Jefferson, “a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.” What is a “tax”? What is an “increase”? what is “new”? The boring legal questions will roll on and on.

Yes, to overrule the Court by constitutional amendment. Congress must approve the amendment. But James Madison proposed a better solution which almost became part of the Constitution. Constitutional change, Madison argued, should be initiated by the states, and, if three-fourths of the states agree, the amendment should become part of the Constitution. That simple little amendment would change the nature of our democracy. If we had the Madison amendment process, we would have a more accurate gauge as to whether the people are in fact consenting to the decisions of the national government, especially those of the Court.

We should adopt Madison’s solution to restore some consent of the governed and to provide a check on the Court and the federal government. Congress should not have any approval or veto power. As Madison said, “The assent of the National Legislature ought not to be required thereto.”

Madison’s Article V required Congress to propose an amendment on application of two-thirds of the states:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary, or on the application of two-thirds of the Legislatures of the several States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution which shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part thereof, when the same shall have been ratified by three fourths at least of the Legislatures of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress.

Madison believed his amendment process was appropriate since the states—whose sovereignty had been established by the Treaty of Paris in 1783—were creating the Constitution and should, of course, be able to change it. Madison’s version of Article V was not opposed until the Convention’s closing hours on September 15, when Gouverneur Morris of New York presented an amendment that changed Madison’s proposal into the never-used convention method we now have. Morris’s motion deleted the italicized portion of Madison’s proposal and replaced it with new language providing that Congress “on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several states shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments.” Madison, apparently as a political necessity, acceded to Morris’s change but noted that “difficulties might arise as to form, the quorum, etc., which in constitutional regulations ought to be as much as possible avoided.”

Our present Article V, because of Gouverneur Morris, suffers from a fatal flaw. It makes Congress a gatekeeper under both methods for proposing constitutional amendments: under the first. Congress has a direct veto—two-thirds of both Houses must approve the amendment before it can be proposed to the states; and under the convention method, it is unclear what powers that convention would have and whether they could be effectively limited. Congress also has the power to fashion the call of the convention in a way to make a good result unlikely. The convention approach is so uncertain that it has not been, and never will be, used.

Article V requires Congress to consider proposals for limiting the power of the federal government. Gouverneur Morris’s version of Article V twisted the basic constitutional legal relationship—instead of a delegation of power from a principal to an agent which, of necessity, would be revocable, the Constitution became a contract between the governors and the governed which could not be changed except by the mutual consent of both parties. The governors generally choose not to consent. In 1787, the states, like Dr. Frankenstein, built a creature and lost control of it.

The Madison Amendment process would give an accurate gauge of whether the people are really consenting to the decisions of the Supreme Court. The Court would decide cases just as it does now, but the people—through three-fourths of the states—would hold a deliberative vehicle to enable them to correct its errors. The amending power becomes a realistic check on the Court. Indeed, the existence of the power is itself a check.

The present amendment system—because of the congressional gatekeeper—grants the three national branches of government a practical immunity from change. Since the first 11 amendments were adopted, only one amendment, the 22nd (presidential term limits), has curtailed the power of a national branch. (The 27th, the ban on Congress raising its own pay, does also, but by its peculiar history—proposed in 1789 as part of the original Bill of Rights and adopted in 1992—it effectively avoided the restraints of Article V.) The remaining amendments cover housekeeping (electoral college, presidential succession), and at least one, the 16th (income tax), adds a major new national power. But most amendments limit the power of the states—the direct election of senators (previously elected by the state legislature). Prohibition and women’s suffrage (previously state issues), anti-poll tax, and the extension of the franchise to 18-year-olds.

Congress is willing to propose amendments which will weaken state power if ratified. But, as the proposed amendments for term limits and the balanced budget show. Congress will not give the states and the people the opportunity to ratify amendments limiting national power. Congress prefers that the Court, rather than the amending process, act as our system’s agent of constitutional change. The present clause is a one-way street. Madison’s amendment process would make the street two-way. The states would be able to amend the Constitution without first obtaining the consent of the government they want to control.

The Madison process would focus debate on federalism and our current government. Perhaps the states would wish to reexamine the sweeping, nationalizing decisions of John Marshall and the more recent decisions that have turned the states into regional offices of the federal government. Perhaps they would choose a different role for the national judiciary. Whatever the people decide, the Supreme Court would no longer have the last word. A state-initiated amendment process would provide the constitutional system Madison wanted, one that is more balanced and based on self-rule. We would then be able to approach Jefferson’s goal of a government that is as good as the people.

Leave a Reply