Nobody, except the New York Times and its worldwide allies, questions the right and duty of Catholic bishops to raise their public voice on moral issues, and on social issues intertwined with problems of a moral nature. Admittedly, pastoral letters, monita, even encyclicals sound rather hollow today, like trumpets in the desert, laments in a cultural vacuum. After all, democracy means that everybody speaks in a continuous stream; one voice is hardly heard above another; the din of a new Broadway musical battles the word of Christ half a mile away at St. Patrick’s.

Let us note, too, that the marginal position and hence diminished responsibility of the Church and its hierarchy has had a blunting effect on the intellectual acuity of the Church’s spokesmen. In The Challenge of Peace ten years ago, American bishops instructed citizens in “passive resistance” to the invading Soviet hordes. Their fellow bishops in Eastern Europe could have told them that, upon meeting the first “passive resister,” the Soviet soldier would have shot him dead (with 20 others) and then nailed his photograph on every street corner as a warning to the population.

Similar naiveté would have been unimaginable at times when the Church possessed political power—of her own and as part of state power, both resting on the wide and solid faith of collectivities. Those times are gone, first with Jefferson’s and Robespierre’s “wall of separation,” then with the deep secularization of all aspects of life. The Second Vatican Council merely put the seal on the invisible but de facto social contract signed in 1776 and 1789 between a victorious civil society and the Church it had reduced to lobby status.

It is a normal, but in this case very questionably motivated, human impulse on the part of the Catholic hierarchy to seek secular shelters in the raging storms of a hostile, post-Christian world. Yet this is the actual state of things. Instead of referring, as in the past, to the Church’s association with the throne (from the Pharaoh to the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs), the bishops today invoke new potentates in flattering terms: the United Nations, the Common Market, NATO, and “global democracy” (which is a usable term for political football in the United States but is out of place under the pen of spiritual leaders). Besides, while popes and bishops used to castigate emperors and kings (St. Ambrose, Gregory VII, Thomas Becket), pastoral letters and the “Reflections” of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops give unquestioned allegiance to the all-too-human international agencies and bureaucratic gatherings. Morally, the latter deserve little of the trust that the American bishops seem to place in them. I have often walked in the footsteps of United Nations troops “intervening for peace” and seen pillage, rape, and injustice. In the ex-Belgian Congo, Indian U.N. soldiers were feared like the plague; 30 years later, Russian U.N. troopers return to Bosnia after demobilization to continue ravaging land and population. Meanwhile, active Blue Berets, stationed in the Balkans, deal in drugs.

The same is true for the bishops of Europe. True, they would not believe that “Bolshevik troops respect noncooperation” —Soviet soldiers shot to death Bishop Vilmos Apor of Györ in 1945 when he tried to protect 50 women from rape—but they, too, follow the fashion of approving “global interventionism.” They did so during the three centuries of the Crusades, although they try to forget this. To be liberated then were the True Cross, the Holy Land, and Christians living under Muslim rule. In the perspective of the year 1087, this was just as essential and urgent as putting Mr. Aristide back in his presidential palace seems now. The Holy Roman Emperor and the kings of France and England were then the chief crusaders; “the U.N. will be at the center of the new international order,” write the American bishops, in The Harvest of Justice Is Sown in Peace. In other words, back to the Crusades with General Schwarzkopf instead of Richard the Lionhearted, with bombers instead of arrows.

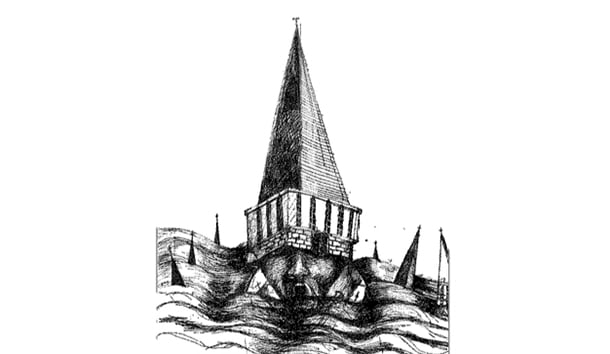

Never before, even when it was persecuted by Caesar, did the Church occupy such an ambiguous position as in our century. The “contract” the Church signed in several stages (separation from the state; alienation of the bourgeoisie, the intellectuals, and the proletariat; acceptance of desacralization; finally, Vatican II) with the new hegemonic power, liberalism, has compelled it to surrender power over morals and culture. In morals, the Church’s voice is not more influential than that of the sects or industrial interests; in culture, we see no artistic, architectural, or musical style inspired by a sense of the sacred. On the contrary, liturgy has itself been cleansed of Latin and elements of veneration; the neutral and the ugly dominate words and gestures. It was expected that the faith would instantly reflourish in ex-communist lands. True, Boris Yeltsin is flanked today by the Patriarch of Moscow; old churches and monasteries are restored; divine service in them comes to life. However, in the race between a newly resuscitated religion and the invading Western lifestyle, the latter seems to win. We can only laugh at Jacques Maritain’s prediction (1951): “When people will have the common will to live together in a world-society, they will want to project a common task. What task? That of conquering liberty.”

The reaction of Eastern Europe’s churchmen is varied. Their reflexes, shaped by 40 years of fear and treachery, are terribly strong but increasingly matched, although in a diffuse form, by a new fear of the devastating Western influence. Under communism, there were small protective shells: family. friendship, circles of study and music. Now drugs, sex, crime, hunger for wealth and luxury undo those ties. In this ocean of filth the Church in Eastern Europe also loses its moorings. What the Communist Party apparatus with its “peace-priests” was unable to achieve is today accomplished by new conflicts between traditionalists and adepts of Vatican II, between liberals and conservatives, between “modernizing” priests forever dissatisfied with the “old structure” and Rome’s careful policy of not rocking the boat.

Political, even ideological alliances are inevitable in Eastern Europe under the circumstances, and they are not basically different from those that the Church feels obliged to make in the West. In the West, the Church has had its right and left wings, and the controversy is still not settled. In Eastern Europe, the left, at least communism so named, is not yet respectable-sounding, while right denotes fascism (this is what Communist Party propaganda had pounded into the man-in-the-street), an even less acceptable label. Caught in the web of a constantly rewritten history, the Church has chosen a cautiously liberal-socialistic path that paints gray on gray, blocks people’s desire to identify themselves with “Rome,” and assimilates the Church to the churches of Western Europe, all singing the praises of the Common Market, United Europe, and the United Nations. If The Harvest of Justice is a middle-of-the-road document, so are the pastoral letters of most Eastern European bishops.

With one difference. The nations of Eastern Europe have not yet been broken on the wheel of material, democratic, and pluralist progress. It is one thing to yearn for consumer goods when bread and milk cost more every week and one’s telephone is usually out of order, another to consent to the nation’s degradation and humiliation. Soviet occupation did not mean these things, since Russia is regarded as the plague: it kills, it does not degrade. But to be an old Catholic nation, and one run by freemasons, cosmopolite parliamentarians, and the media-mob, to be threatened by century-old enemies at one’s borders—this is intolerable. The Church, mealymouthed on these issues, would only create antagonism. Thus the Eastern European Church seems to have chosen. Its words and gestures are liberal, democratic, pluralist, as are some members of the clergy, but when it comes, for example, to reclaiming schools confiscated by the party-state, the bishops know well how to secure their due. The same is true of the religious rights of minorities, such as those of Magyars in Transylvania.

All in all, the separation of church and state has settled nothing, historically. If it is true that the former used to be excessively tied to the latter (was the reverse not true also?), it is equally true that little progress has been made since: today, churches arc subordinated to liberal civil society, its public opinion and ruling ideologues. A document like The Harvest of Justice reads like a United Nations bulletin when speeches have been delivered by all 184 members. What the bishops omit in their liberal enthusiasm is that today’s clear and present danger is not the situation in Bosnia or Haiti—that kind of threat to an area will always be in generous supply—but one-worldism, one clique speaking like Big Brother in the name of humanity, humanitarianism, and humanitarian intervention. The Church ought to know better: in past centuries it never succeeded in uniting even pockets of Christian Europe. Why would the United Nations, the Europe concocted at Brussels, NATO, or some other acronymic organization save the world, bring peace, and harvest justice?

Leave a Reply