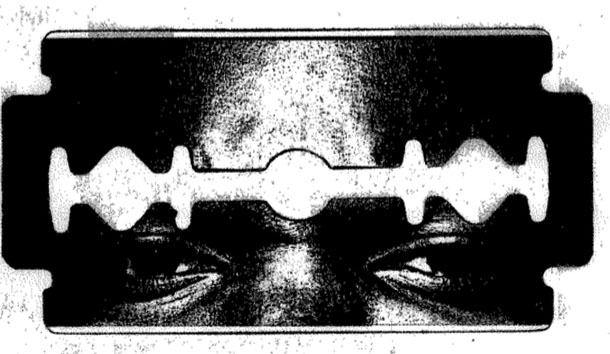

Imagine the devastating effect, even on the mass of young black men who successfully resist the temptation to violence, of Gwen Guthrie’s song Ain’t Nothin’ Coin’ On But The Rent:

Boy, nothing in life is free / That’s why I’m asking you what can you do for me / I’ve got responsibility / So I’m lookin’ for a man who’s got some money in his hand . . . / I’ve got lots of love to give, but I will have to avoid you if you’re unemployed . . . /You’ve got to have something, if you want to be with me . . . / Life’s too serious, love’s too mysterious, a black girl like me needs security . . . / We’re only wasting time if your pockets are empty . . . / No romance with no finance.

Perhaps this moves some young men in the direction of employment (“You’ve got to have a J-O-B if you want to be with me”), but for many—for whom any employment possible in practical terms would clearly be insufficient to satisfy the woman in the song—the song can be only a taunt that makes crime alluring. It is astonishing that more of the deprived and unemployable do not turn to violent crime. I would.

For many it is received wisdom that America’s catastrophically high murder rate is explicable in terms of a tradition of violence inherent in American culture. This belief persists despite the fact that such an “American tradition of violence” requires invocation of an obscure and dubious explanation of violent crime where an obvious and cogent explanation suffices. The blunt truth is that a disproportionate rate of murder by a small number of young black men (whatever its causes) accounts for the shocking level of violent crime. This may well be what white America deserves for inflicting slavery and the residue of slavery on a people (or it would be were the victims of black murderers not overwhelmingly black). Be that as it may, the reality is that the six percent of the American people who are black males commit half of all murders in America and that most of these murders are committed by the small portion of the six percent who are young.

The causation of the black homicide rate is a complex amalgam. The familiar contributing factors include but are not limited to: family instability (particularly illegitimacy and the absence of a father); educational deprivation in a time when extensive education is a necessary condition for a minimal ability to compete; a milieu in which success becomes associated with crime in the young black mind and in which gratification that is not instant is dismissed as unachievable; the taunting of those who have nothing by television families that seem to have everything; the assault on black males’ hopefulness and self-esteem that all of these engender; a system of law enforcement that makes violent crime rational; and, of course, joblessness, prejudice, and drugs. All of these generate an attitude toward educational and occupational pursuits that precludes success.

For many black males these facts greatly increase the likelihood that they will soon be in prison, on parole, or on probation. To be sure, most young black males do not encounter a configuration of factors capable of overcoming their resistance (what we used to call “character”), and most of those who do are able to resist the temptation to violence. But for murderers—and that is the subject—such factors are sufficient. There are other sides to the problem, not the least of which is the black crime caused by black crime: manslaughter by a man who would never have committed a crime had he not correctly believed that in his territory one must kill to survive, or murder by those who would not have become murderers had their lives not been formed in homes, neighborhoods, and schools plagued by violent crime.

These destructive forces are in part the result of the historical American attitude toward and treatment of blacks {how large a part being an issue of considerable controversy). Thus, there is much to say for the view focused on an “American tradition of violence” if this means a historical American tradition of violence toward blacks. After all, we did enslave them and treat them for a hundred years thereafter as people unfit to be in the same schools as our children. This fact does undercut any self-righteous and self-congratulatory dismissals of the view that attributes black social problems to the experience of slavery and its aftermath.

However, to characterize the white treatment of blacks as representing a “tradition of violence” unqualified by color is to make—and is meant to make—an entirely different argument: it implies, indeed means, that a “tradition of violence” infuses so much of American culture that it would engender enormously high rates of violent crime even if America were all-white. This is, in fact, what most of those who speak of a “tradition of violence” have in mind.

The truth is that crimes in which both perpetrator and victim are white give us little reason to believe that the American tradition of violence is much greater than that of other nations. International homicide statistics are difficult to interpret; different nations’ differing methodology and the accurate collection of data are but two of a host of methodological problems. Interpol figures show that America’s homicide rate is only slightly higher than those of Canada and the Scandinavian countries (and only an eighth that of Lesotho and a sixth that of the Philippines), while the World Health Organization posits an American rate at least double that of other modern societies. Moreover, as David Ward points out, any comparison of the United States with homogenous societies is rather silly. There are American states with homicide rates lower than that of nearly any European nation and states—especially the most heterogeneous ones—with rates that dwarf any European nation’s.

Were it not for the disproportionate black contribution (of victims as well as perpetrators), the United States would have an enviable record according to some data and a poor, but not dramatically so, record according to others. The Interpol statistics, for example, imply that, if the black murder rate were the same as that of whites, the resulting American murder rate would be below that of Luxembourg and only slightly above that of Malta. Even according to the WHO statistics, the rate would not be dramatically out of line even when compared with relatively homogenous industrialized countries.

Whatever the fears of whites, it is blacks who are in fact the victims of black murderers. Ninety percent of white victims are murdered by whites and 95 percent of black victims are murdered by blacks. The near halving of the murder rate that might result from reducing the black murder rate to the same level as that of whites would benefit blacks far more than whites.

To avoid an effect, you need to eradicate one necessary component in the configuration of causal factors. If this were not the ease, we would still be dying of a host of diseases that have long since been cured by the discovery and annihilation of a single factor. The common argument that “you cannot do anything about crime until you solve the cause of crime” is correct only in the trivial sense that to “do something about crime” you must do something about at least one of the causal elements. The choice of which element to deal with will depend on how one assesses the moral and economic cost of removing one or the other. But the causal logic is the same whichever element one prefers to attack; the proponent of expenditure for enforcement and the proponent of expenditure for education are both attempting to eliminate a necessary condition for crime and neither can meaningfully accuse the other of not attempting to deal with “the cause of crime.”

Even if the liberal assumption is correct, that poverty, low self-esteem, poor education, and the like are all causes of crime, this does not conflict with the view that emphasizes ineffective law enforcement and lenient sentencing. Conservatives often confuse liberal assumptions about the causes of crime with a willingness to view these causes as somehow disproving the ability of better law enforcement to decrease crime and to see the causes as rendering rigorous enforcement (and harsh punishment) morally unjustified. The second is a moral question, and I would rather wait for the cows to come home than to try to answer a moral question; at least the cows will, sooner or later, come home. The first is a logical and empirical issue, and neither logic nor experience gives us reason to doubt that better law enforcement reduces crime. Even if we ignore the deterrent effect of punishment, a murderer in prison obviously cannot commit another murder outside of prison.

Crime by a relatively few blacks is destroying the black community. The criminals in this small group are not the breed of times past. While it is now fashionable to ridicule the psychological explanations of crime that gained favor in the 1940’s, it may well be that, in times of strong social values, powerful psychological urges are required to overcome resistance to crime. The few blacks who today commit vastly disproportionate numbers of violent crimes suffer not from emotions too powerful to resist, but from a lack of conscience itself (owing in large part to the absence of a father). For such people, fear is the only deterrent.

This means that an increase in the probability of the criminal’s being caught and punished will decrease the rate of crime, even if all other causal variables remain unchanged. Indeed, the decrease in crime is likely to decrease the strength of the other causal contributors to crime. (All this can be said of an increase in punishment—as opposed to probability of being caught—but this is much less effective because the criminal who correctly believes that there is little chance of his being caught hardly cares about the severity of the punishment.)

It no longer matters whether the historical treatment of blacks by white America is responsible for violent black crime. Whatever the ultimate cause, crime renders impossible any solution to the black community’s otherwise solvable problems. Solutions will remain impossible as long as significant numbers of influential blacks and whites insist that the social forces suppressing blacks also suppress black free will and, therefore, justify leniency. This view confuses the distinction between a possibly justified analysis of legal and moral desserts (i.e., one that sees “free will” as a fiction or as an incomprehensible or meaningless concept) and the role in determining behavior played by a belief in free will.

Our legal system assumes that there is free will and that a reduction of free will reduces guilt and, therefore, justifiable punishment. Any legal system that failed to assume this would be likely to careen into self-parody by saying “you can’t do this, but since you can’t help it, you can do this” (a view permissible only for the legally insane). But even if a legal system took a purely operationalist view—and even if the notion of “free will” were in fact an incoherent or meaningless concept—our legal system would have to assume free will because one of the vital causal forces determining behavior—even in a deterministic world—is the individual’s belief that there is “free will.”

We all act in a way that feels free. But we do not believe that this has anything to do with how we treat others. That must be encouraged by our society telling us that free will makes us responsible. To the extent that a society does not do this, it is much more likely to produce people with a conscience insufficient to keep them from killing.

One of the many, and one of the most effective, ways in which society reinforces responsibility is the threat of punishment. This potential punishment exerts its influence even when the individual does not consciously consider the likely results of the potential behavior; it exerts its influence from the time it is internalized by the conscience. In other words: tell someone that for him to commit theft is not really wrong, or if wrong, not his fault, or if his fault, not punishable, and he will be less likely to resist the temptation to steal.

As a rule, the stronger the potential punishment, the greater the internalized resistance to committing the crime. This resistance comes into play long before conscious thought does. (Unlike the small child, we have no conscious battle over whether to steal the shiny object; most of us have long since internalized a resistance to considering such an act.) Thus, if a person feels an impulse to kick you in the shin, the likelihood of his doing so will depend upon the strength of his resistance to doing so. The stronger the punishment, the stronger the resistance he internalizes. This is true even if the impulse is emotional (anger) and when he is not consciously considering the punishment. It is certainly true when the impulse is primarily “rational” and the cogitation conscious (bank robbery). And this is all true even if the determinist is almost entirely correct in his identification of the psychological, familial, economic, and social causes of the behavior, and even if free will (as opposed to a belief in free will) plays no role.

Black Americans have generally remained a friendly people in spite of their oppression. Indeed, this kindness would be unbelievable if we did not know it were true. But where slavery and ostracism failed to unleash black rage, black crime—and the fear and destruction this crime causes in the black community—may succeed.

The rate of violent crime can be lowered—reducing the slaughter that kills blacks and the terror that grips whites—only if it is acknowledged that blacks are responsible for most violent crime. The problem—which is not merely the problem of crime but the problem of the black community’s survival and success—can be solved. But it cannot be solved without facing the fact that a small number of irredeemably violent people are destroying the possibility of solution. The black majority alone cannot solve the problems of the black community, and a reduction of black violence is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the solution of its problems; the commitment and resources of the entire society are required. However, the problems cannot be solved at all unless the black majority can socialize the rest of the members of its community to meet the norms that must be met in any community that is to survive, and there is no chance whatever that members of the black majority will be able to do this while being picked off one by one on streets that a relatively small number of predators now control.

The black community will not solve its problems if it in effect excuses black murder on the grounds that “America is a racist society.” The conservative abhors this view because it implies that the murderer bears little responsibility for his crime. The black, on the other hand, feels the term to be justified because he knows that the white unfairly reserves for the majority of black males expectations the white would not have of whites. The black is utterly correct; attaching to an individual member of the black group expectations that, even when statistically true of the group, are not true of the individual member is a perfectly reasonable definition of “racist.” It is “racist” in its effect on the innocent individual, even though there is no avoiding the tendency to perceive the individual through a statistical lens and no possibility of assessing a person one hardly knows “as an individual.”

In any case, we are at the point where it would make no difference even if black violence were entirely the fault of white America. Black survival requires that the black majority not be destroyed by a black minority, and it makes no sense for whites to let a sense of guilt—whether justified or not no longer matters—lead them to blame such depradations on an “American tradition of violence” of which there is little evidence. False explanations seldom lead to solutions.

Leave a Reply