The North German Plain is not an exciting place. It lacks the charm of the Palatinate, the fairytale quality of the Middle Rhineland, or the drama of the Bavarian Alps. It is peopled by staid burghers who are hard-working, practical, and (in contrast to the Oberpfälzers, say) rather quiet. It rains a lot, and now in early January the drizzle is driven by gusts of wind that make it feel much colder than the actual 43 degrees.

In short, Lower Saxony and Westphalia are not a natural tourist destination. Having spent the Silvesterabend with German friends in Siegburg—a pleasant town between Cologne and Bonn—I nevertheless decided to venture into these uninviting parts, for  two reasons. The first was to visit Osnabrück, where my late father spent almost four years as a PoW in the Oflag VI-C. On the night of December 6, 1944, the RAF missed the nearby train junction and hit the camp. 2nd Lt. Konstantin Trifkovic survived (otherwise you wouldn’t be reading these lines), but 112 of his fellow officers were killed and over 60 badly wounded. There is a memorial Serbian Orthodox church near the site, with a crypt containing the remains of many senior officers of the Royal Yugoslav Army who refused to go back to Tito’s tender mercies after 1945. There is also a lonely camp barrack left as a monument, a flimsy wooden structure currently threatened by developers and city planners. It was one of the places I had to visit before I die.

two reasons. The first was to visit Osnabrück, where my late father spent almost four years as a PoW in the Oflag VI-C. On the night of December 6, 1944, the RAF missed the nearby train junction and hit the camp. 2nd Lt. Konstantin Trifkovic survived (otherwise you wouldn’t be reading these lines), but 112 of his fellow officers were killed and over 60 badly wounded. There is a memorial Serbian Orthodox church near the site, with a crypt containing the remains of many senior officers of the Royal Yugoslav Army who refused to go back to Tito’s tender mercies after 1945. There is also a lonely camp barrack left as a monument, a flimsy wooden structure currently threatened by developers and city planners. It was one of the places I had to visit before I die.

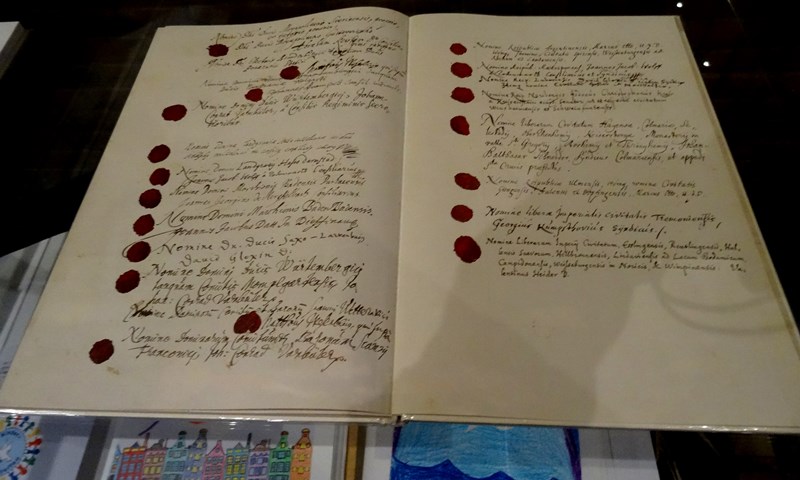

The second reason was Münster, a marvelous city which was well-nigh flattened by Allied bombs in 1944-45 but has sprang back to life. There’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, a  XIII century gem which blends late Romanesque and early Gothic styles. A stone’s throw away, at the Prinzipalmarkt, there’s St. Lambert’s Church, a late-XIV century Gothic masterpiece, with three cages hanging from its tower above the clock face. In 1535 these cages were used to display the corpses of Jan van Leiden and other radical Anabaptist leaders of the Münster Rebellion, who advocated polygamy and renunciation of all property. But above all I was keen to visit the Gothic town hall in which the Peace of Westphalia was signed in 1648, thus

XIII century gem which blends late Romanesque and early Gothic styles. A stone’s throw away, at the Prinzipalmarkt, there’s St. Lambert’s Church, a late-XIV century Gothic masterpiece, with three cages hanging from its tower above the clock face. In 1535 these cages were used to display the corpses of Jan van Leiden and other radical Anabaptist leaders of the Münster Rebellion, who advocated polygamy and renunciation of all property. But above all I was keen to visit the Gothic town hall in which the Peace of Westphalia was signed in 1648, thus  ending the Thirty Years’ War.

ending the Thirty Years’ War.

That war was a tragedy of metahistorical proportions. The Hobbesian mayhem that struck Europe in the first half of the XVIIth century was not an event, or a series of events, befitting the designation of “a war.” The plural form, as in the Napoleonic Wars, would be more apt. It was a pancontinental orgy of destruction which involved all major players except Russia, and continued, relentlessly, long after its early instigators and participants were all dead. The conflict was not a Clausewitzian “continuation of politics by other means;” it was a substitution of politics by the torch and the sword. It was absurd, not only morally but technically. The balance between ends and means in the decision-making calculus—tenuous to start with—was lost to fear, pride, blood lust, va-banque adventurism, fanaticism, and numbing inertia well before the war entered its most destructive phase in the 1630’s. These sentiments are present in varying degrees in all wars. In Europe between 1618, starting with the Defenestration of Prague, and 1648 they were dominant. Although  religious tension contributed to the outbreak of the war, the link was far from straightforward. As Peter H. Wilson explained in his semidefinitive 2010 study The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy, all Christian confessions sprang from common roots, but developed a momentum of their own due to vested material interests, social concerns for status and prestige, and the psychological need to belong and to define that belonging by distancing oneself from those holding different views.

religious tension contributed to the outbreak of the war, the link was far from straightforward. As Peter H. Wilson explained in his semidefinitive 2010 study The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy, all Christian confessions sprang from common roots, but developed a momentum of their own due to vested material interests, social concerns for status and prestige, and the psychological need to belong and to define that belonging by distancing oneself from those holding different views.

Eastern Central Europeans, on the other hand, realized that confessional disputes impaired their ability to fight the Ottomans who represented a threat to all Christians. Among the upper crust the common veneration of classical forms helped raise the exchange of ideas above sectarianism, and even during the war Emperor Ferdinand chose Protestants as imperial poets laureate.

Confessional rights, claims, and grievances, intertwined with constitutional disputes, were significant in the overall mix of motives and justifications for action. On the other hand, France was an ally of Lutheran Sweden and Calvinist Holland against  Catolicissima Spain and against the Catholic emperor, up to one third of whose soldiers were Protestants. Sweden fought her coreligionist Denmark, while Saxony, Brandenburg, and others changed sides during the conflict. Protestant Scots served in the French, Polish, and Imperial armies; many Scots and Irish Catholics fought for Sweden, Denmark, and Holland; and many men converted to the faith of their current employer. All of them ignored Pope Urban VIII, a cynical Barberini “compromised by his own opportunism” and chronically jealous of the Habsburg power, in Spain and the Empire alike.

Catolicissima Spain and against the Catholic emperor, up to one third of whose soldiers were Protestants. Sweden fought her coreligionist Denmark, while Saxony, Brandenburg, and others changed sides during the conflict. Protestant Scots served in the French, Polish, and Imperial armies; many Scots and Irish Catholics fought for Sweden, Denmark, and Holland; and many men converted to the faith of their current employer. All of them ignored Pope Urban VIII, a cynical Barberini “compromised by his own opportunism” and chronically jealous of the Habsburg power, in Spain and the Empire alike.

The Thirty Years War became infamous for its all-pervasive violence and unremitting destruction even before it was over. In the early XIXth century Schiller and other German Romantics, obsessed with death, destruction, and the loss of identity, merged the collective memory of plunder, mass murder, and plague with a sense of blameless German victimhood and of merciless foreign savagery, with the promise of eventual redemption through the rise of a new, stronger German nation from the ashes. It was a powerful and dangerous mix, with lasting significance for the Germans and for the rest of Europe.

The resilience of the municipal and provincial structures in the German-speaking lands during the Thirty Years’ War—and especially here in the northern plains of Westphalia and Northern Saxony—was remarkable. Territorial rule did not collapse, and administrators in Münster, Osnabrück, and elsewhere adapted under seemingly impossible conditions, just as they did under the Allied bombs and in the ruins after 1945. An impressive people.

Leave a Reply