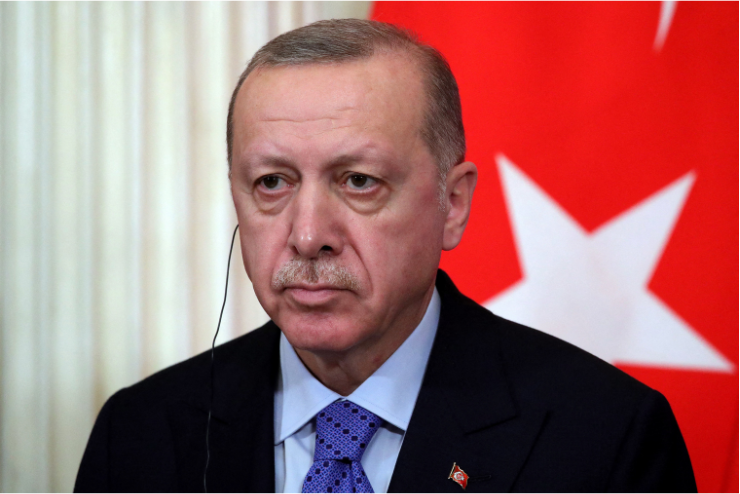

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been in power for over two decades, first as Turkey’s prime minister and since 2014 as president. After the new constitution was adopted in 2017, he has enjoyed unprecedented powers, which he intends to keep for many years to come.

“The Sultan” will face three opponents in the first round of the presidential election on 14 May, and for the first time, Erdoğan’s political future appears uncertain since his Justice and Development (AK) Party came to power in 2003. His main opponent is 74-year-old Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of the center-left CHP party. The other two candidates are Muharrem İnce of the centre-left Homeland Party, which split from the CHP in 2020, and the rightist Sinan Oğan.

Recent polls indicate that no contender will win in the first round: Kılıçdaroğlu’s current support is 47 percent, while Erdoğan’s is just over 43 percent. Because İnce has split the left-of-center vote—his support stands at seven percent—he will likely deny Kılıçdaroğlu a victory in the first round. Depending on whether his supporters abstain in the second round, they may even give Erdoğan a solid chance for another term.

Since 2018, Turkey has suffered several fiscal crises, the lira has slumped, and inflation has reached 80 percent. On Feb. 6, two devastating earthquakes killed some 50 thousand people in the east of the country. Yet the economy has shown surprising resilience. Istanbul has experienced an impressive construction boom since my previous visit in 2013. In any event, Erdoğan’s core support in the Anatolian heartland and the working-class districts of Turkish cities is not shaped by economic considerations but by religious conviction, nationalist sentiment, and regional and personal loyalties. For millions of Turks, he is the man who has revived Turkey’s standing as a regional power. Not even the sluggish initial government response to the earthquake relief has inflicted a major blow on the AKP numbers: for religious conservatives, it was Allah’s will, and there is little that men can do to alter the outcome.

Erdoğan is also playing the nationalist card, and the U.S. has inadvertently helped him. At the end of March, the American ambassador in Ankara, Jeff Flake, went to the headquarters of the CHP, where he had a meeting with the party leader and candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. Erdoğan’s rival later said that he discussed with Flake “matters of mutual interest between the two countries.” This was a ham-fisted gesture by Washington, and it prompted Erdoğan to formally cut all ties with Flake: if he has the audacity to ask him for a meeting, Erdoğan said, the door will be slammed in his face.

Just a week later, Erdoğan received with great pomp Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. The visit sent a clear signal to the Turkish public that Moscow would like to see Erdoğan win. Their meeting took place behind closed doors and the confidential conversation was not followed by any press release. Following the failed 2016 coup attempt, when Putin became one of the first global leaders to reach out to Erdogan, Turkish-Russian political and economic relations have been on a constant, steady upswing. Russia is Turkey’s key economic partrner and Russian visitors—some seven million are expected this year—are a vitally important source of income for Turkey’s tourist industry.

At the same time, anti-Americanism in Turkey is at an all-time high. The Turks of all political hues blame the Biden administration for unconcealed U.S. support for Greece over the disputed economic zones in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. They are also angered by the U.S. military and logistical support for the Kurds in Syria, whom the government in Ankara regards as being entirely controlled by the PKK, a designated terrorist group.

Putin’s possible arrival at the end of April for the inauguration of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant—Turkey’s first, built with the key contribution of Rosatom—would be a boon for Erdoğan. It would additionally revive his regional prestige and remind Turkish voters of the tangible benefits of cooperation with Russia.

Also on the foreign policy front, Erdoğan will likely benefit from the ongoing thaw in relations with Syria and Iran. For many Turks, especially in the east of the country, any move likely to facilitate the return of Syrian refugees to their home country—and there are almost four million of them!—will be seen as welcome news. Moscow will host a meeting of foreign ministers from Ankara, Tehran and Damascus in early May, handily just one week before the Turkish election.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a wily, seasoned politician who identifies Turkey with himself. He has won thirteen nationwide polls and intends to win the fourteenth. He may have other cards up his sleeve—if the vote goes against him—to ensure that he still wins the count. After the failed coup in 2016, he packed the courts with his supporters. Even his opponents privately admit that it is hard to imagine his orderly departure from the helm.

Leave a Reply