It often happens that when a Greek or Latin word is given a new lease on life in one of the major modern languages, and especially in English, the original meaning of the word may be replaced by a rather different one. This is particularly the case when a word, which was a strongly transitive verb in the classical context, is resuscitated as a generic noun in the modern diction. The word evolution is a case in point.

The root of that all-important modern noun is the Latin verb evolvere. Whether used by historians like Tacitus and Livy or by poets like Ovid and Catullus or by philosophers like Lucretius, Seneca, and Cicero, the verb evolvere either meant to eject something with a rolling or coiling motion, or to cause something to flow out or roll out from somewhere, or to unwind something, or to unwrap or uncover something. In all these cases it was clearly assumed that the thing or the object of the action had already been there. Only one and uncertain case is found in classical Latin literature for the noun form evolutio of the verb evolvere, according to the testimony of the two-volume Oxford Latin-English dictionary.

The aura that has grown around the modern word evolution is precisely the make-believe that something, and often something very big, can ultimately come out from somewhere where it had not been beforehand, provided the steps of that process are very numerous and practically undetectable.

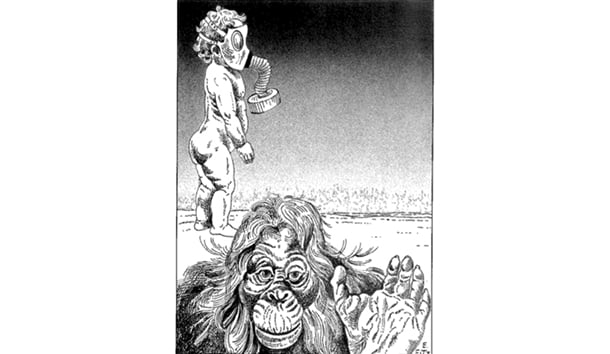

This is not a new-fangled diagnosis of the process imaginatively called evolution. More than a hundred years have already gone by since the public was regaled with an inimitable dictum produced with an eye on Darwinism: “A logical theft is more easily committed piecemeal than wholesale. Surely it is a mean device for a philosopher to crib causation by hairsbreadths, to put it out at compound interest through all time and then disown the debt.”

Those evolutionists who want no part of an evolutionism steeped in the foregoing trick cannot, however, make nonexistent the frequent presentation of evolution in that deceitful sense. Furthermore, they should feel gratified when such a trick is identified and discredited right at the very start of the discussion. Clear air is a necessity not only for physical survival but also for mental balance.

Once castrated of this pseudogenerative power to produce rabbits and bigger pieces, such as elephants and dinosaurs, to say nothing of such intangible jewels as the human mind, from under an empty hat, the word evolution should perhaps better yield to the word development. This word, so useful and modest—just think of John Henry Newman’s masterful articulation of it—has at least the advantage of being much closer to the original meaning of evolvere, that is, to the unfolding of something that in essence at least had already been there.

This substitution will be violently resisted by Darwinists, for the essence of Darwinism is that there are no essences, except one essence, which is sheer matter. Liberal Christian admirers of Darwin would now recall his reference to the Creator at the end of the Origin of Species. They had better do their homework properly. That reference, inserted only from the second edition on, prompted Darwin to speak privately of his shame for “having truckled to public opinion.” The high Victorian times still wanted to have a bit of religious wrapping about rank irreligiosity. Darwin should have felt even more ashamed for having spoken in should have felt even more ashamed for having spoken in his Autobiography of his imperceptibly slow “evolution” from belief into mere agnosticism. As one who through much of his adult life had to dissimulate his true views lest a deeply religious and beloved wife be hurt, Darwin finally came to believe that he was not dissimulating anything.

He might have been cured of his illusion about the evolution of his religious beliefs had he reread in his late years his early Notebooks. Available since the early 1970’s in easily accessible edition, those Notebooks make it absolutely clear that the Darwin of the late 1830’s was a crude and crusading materialist.

There was no gradual evolution from the official naturalist of the Beagle who, as behooved a good fundamentalist, had lectured shipmates with Bible in hand on the evil of swearing, to the author of those Notebooks. The transition was rather rapid, indicating a sudden and thorough disillusion which turns one’s erstwhile object of love into a target of hatred to be exposed and destroyed by all possible means.

Darwin quickly isolated the notion of species as the central target of his attacks on God, supernatural, revelation, and Bible. This showed not so much his acumen as the patently indefensible character of the production on the third and fifth days of plants and animals “according to their kinds” as a divine warrant of the fixity of species. What is a proof of uncommon acumen is Darwin’s relentless spotting of data, direct and circumstantial, in support of his evolutionary vision in which all, from the simplest organism to man, followed with inevitable necessity once the original soup of life was available. To his credit, Darwin did not make the claim made by Haeckel and others that science had ascertained the existence and qualifies of the original soup. But his conviction was firm about the purely natural emergence of such a soup some billions of years ago.

However, Darwin never appreciated what at one point dawned on his most trusted ally, T.H. Huxley, that the mental spectacle of a forever-evolving life was a metaphysical vision. That Herbert Spencer, who with enormous verbal skill kept portraying the evolution of the most nonhomogeneous from the most homogeneous, was for Darwin one of the greatest philosophers of all times, shows something of Darwin’s blindness to elementary fallacies in reasoning.

Reason commanded no encomiums on Darwin’s part. His contemptuous remarks about the minds of geniuses were so many defense mechanisms against facing up to the problem of the mind, the greatest and most decisive problem to be faced by evolutionists. Darwinian or other. Not once did Darwin ponder the nature of purposeful action. Not once did he ask himself the question whether his lifelong and most purposeful commitment to the purpose of proving that there was no purpose was not a slap in his own mental face.

The only time when Darwin performed creditably in philosophical matters relating to his evolutionary ideology came when he jotted on a slip of paper, which he kept in his copy of Chalmers’ Vestiges of Creation, the warning addressed to himself: “Never say higher or lower.” He did not fully remember the gist of that warning, namely, that a scientific theory (as distinct from a scientistic ideology) permitted no value judgments.

He never suspected the irony of his answering within the framework of “how” the questions about “why” and “for what purpose.” He recognized, however, that there was something unsatisfactory with the “how” he held high, or the selective impact of environment on the fact that offspring were always, however slightly, different from their parents. That “how,” supported by genetics as it may be, is still elusive. Indeed, so elusive as to have produced a unique feature in the history of science. Whereas in physics and chemistry the conversion of scientists to a new major theory becomes complete within one generation, in biology a respectable minority has maintained itself for now over four generations against the majority position represented by Darwinists.

The latest evidence of the deep dissatisfaction felt about Darwinism has come from strictly Darwinistic circles. Despair about Darwinism is the driving force behind that recent rush to the idea of punctuated evolution. In no sense an explanation, the theory of punctuated evolution is a mere verbalization demanded by the fact that the geological record almost invariably shows bursts of new forms and hardly ever a slow gradual process as demanded by classical Darwinism. The radical opposition to religion in general and to Christianity in particular on the part of the chief spokesmen of punctuated evolution is of a piece with the antireligious origins of Darwinism.

Many Christians have only themselves to blame if their reaction to Darwinism justifies Huxley’s remark that “extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules.” There is no intellectual saving grace for those who oppose long geological ages and the exceedingly variegated fossil record with a swearing by the six-day creation story as a literal record of what happened. It is rarely remembered that their hapless wrestling with Scriptures and science is but the latest act in that intellectual tragedy which Luther and Calvin initiated by their lengthy commentaries on Genesis 1-3. The strictest literal interpretation of the creation story told there was upheld by both to the hilt. Present-day Lutherans and Calvinists cater only to the uninformed when, proud of the “main-line” status accorded to them by the secularist media, they hold high the “reasonableness” of their tradition against the “unreasonability” of fundamentalist Protestants.

A hermeneutics which sets limits to the literal interpretation must come to terms with the fact that the Scriptures were born within the Church and not the other way around, and that therefore only a Church with an infallible magisterium can guarantee the inerrancy of the Scriptures.

This, of course, brings us to the branch of Christendom known as Roman Catholicism. The near-escape of papal infallibility from the clutches of the Galileo case taught Catholics a lesson which stood them in good stead in the decades immediately following Darwin. Their resistance to Darwinism was from the start done more with an eye on plain philosophy than on scriptural or dogmatic texts. The essentially philosophical objections of St. John Mivart, a Catholic biologist, to Darwin’s theory represented one of the two main attacks that upset Darwin considerably. The other was the demonstration by F. Jenkin, a Scottish engineer, that the laws of statistics did not favor at all the evolutionary mechanism known as natural selection.

The mathematical analysis carried out by R. A. Fisher in the late 1920’s made natural selection appear in a less unfavorable light. Of course, no mathematics could provide in the first place the reality of co-breeding individuals whose totality is the species. The reality of species has not ceased to remain a pointer to a fundamental question in philosophy, namely, the ability of the mind to see the universal in the individual and particular. It was with an eye on such a question that a philosopher of science, with obvious sympathy for Darwinism but with a rank miscomprehension of metaphysics, proposed in the early 1970’s the working out of a biological metaphysics!

The proposal was typical of the thinking of those Darwinists who try to stake out a “humanist” position that affirms materialism with profuse accolades to human values. It is that “humanist” form of Darwinist materialism that alone should be of concern to Christians who take their stand on the eternal validity of values, among them the value of brotherly love. In that “humanist” form brotherly love is evoked through despiritualized labels such as “kin-selection” and “altruism,” lest the unwary be alerted to the fact that beneath the Darwinian guise of humanness there lurks a “scientific materialism as the best myth humankind may ever have.”

That “humanism” ought to be unmasked at regular intervals, a task which is essentialh’ philosophical. Only with some philosophical acumen and a great deal of common sense can one show that the reasoning of Darwinists is either contradictory, or simply a tacit assumption of basic realities they try to disprove and discredit. Among these basic realities are mind, purpose, and ethical principles. That they cannot be accounted for within Darwinist perspectives has time and again been admitted by leading Darwinists.

To be sure, only a few of them did come across as candidly as did T.H. Huxley a hundred years ago when he warned against seeing a “moral flavour” in the survival of the fittest. Only a few of them admitted as candidly as did Huxley’s grandson. Sir Andrew Huxley, that no scientific clue has yet emerged for the origin of consciousness. He also stated in the same breath that the origin of life is still an unsolved problem.

Most Darwinists have done their best to create the illusion that there is no major fault with Darwinism. Yet the fact is that the empirical evidence for the transformation of species under environmental pressure is still circumstantial. The measure of effectiveness that can be attributed to the same mechanism diminishes in the measure in which one considers the transition between ever-larger biological groups, from genera through families, orders, classes, to phyla and kingdoms.

None of these remarks should be construed as a rejection of the chief merit of Darwinism, which in fact assures its genuine scientific status. By ignoring all considerations of design and purpose as being possibly at work in living organisms, Darwinists cultivate biology as a science which deals only with empirical data and their correlations in the space-time continuum.

Unfortunately, the chief glory of Darwinistic biology has also become its chief delusion. The methodical elimination of questions about the reality of design and purpose has been taken by many Darwinists as a proof that design and purpose do not exist. The miscomprehension about the limitations of the scientific method also plagues many Christians who expect science to deliver proofs of design and purpose. They fail to see that such proofs can only come from that philosophy which they all too often consider an enemy of faith. Once they lose their hold on philosophy they can at best come up with poetry in prose, as illustrated by Teilhard de Chardin’s flights of fancy.

Father Teilhard could do far worse. In the trenches of World War I, where he served as a stretcher bearer, he wrote glowing encomiums on the war as an unsurpassed means of promoting the heroic qualities of the race. It could not be unknown to him that several members of the German General Staff had some years earlier published books in which their war plans were justified on the same Darwinist grounds. Nor could the two volumes of Darwin’s letters published in 1890 be unknown to young Father Teilhard, a prominent supporter of the Piltdown man and other Darwinist causes. Those volumes contained the evidence that Darwin believed that evolution justified the Russians promoting the higher race by smashing the Turkish armies.

It is not known what Father Teilhard’s reactions were to Shaw’s preface to his Heartbreak House, published in the wake of World War I. In that war, machine guns (produced and marketed with sales-pitches reminiscent of Darwinist mottos) performed time and again as effectively in a few hours’ time as did the bombs that fell on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in a second or two. In that preface Shaw pinpointed “Anglosaxon” Darwinism as a chief ideological source of Prussian militarism: “We taught Prussia this religion; and Prussia bettered our instructions so effectively that we presently found ourselves confronted with the necessity of destroying Prussia to prevent Prussia from destroying us. And that has just ended in each destroying the other to an extent doubtfully reparable in our time.”

Of course, most Darwinists try to find refuge in circumlocutions or in sullen silence when reminded of the true nature of their ideology. In doing so they merely imitate Darwin, who from the comfort of his gentry residence largely ignored Marx when the latter reminded him that class struggle and the struggle for life had much in common. The “humanization” of Darwinism is a far greater threat to human well-being—intellectual, ethical, and spiritual—than are outspoken endorsements of war by prominent Darwinists such as Sir Arthur Keith. His praises of the pruning effect of wars, which coincided with Stalin’s and Hider’s preparations for World War II, may sober up dreamy-eyed captives to the myth of progress, biological, cultural, and ethical, defined in terms of Darwinian evolution.

Only a few among those dreamers were as candid as Aldous Huxley, who attributed the favorable reception given Darwinism to the liberation through it from transcendent ethical and sexual norms. Only a few woke up as he did to the need to take a searching look at the word evolution.

Evolution should deserve no sympathy if it serves as a proof that something can come out from where it had not been at least “in embryo.” This is not to suggest that in the manner of preformationists a homunculus should be imagined inside the membrane of the human sperm or that a soul should be attributed to each and every pollen drifting through the air, because human soul or mind clearly crowns the evolutionary process. What is suggested is that evolution or, rather the vast spectacle of the gradations of life which life has taken on over billions of years and through a mechanism which is at best most imperfectly understood, be recognized for what it truly is: a vision which is primarily and ultimately metaphysical.

Man is capable of such vision precisely because his nature transcends what is merely physical. Taken in that perspective, the word evolution should give no fear to the Christian. After all, his chief perspective, main comfort, and supreme concern ought to remain in the words: “What does profit a man if he gains the whole world but in the process he loses his soul?”-and-“Don’t be afraid of those who kill the body but are not able to kill the soul”—and—”Be afraid only of the one who can relegate both body and soul to the gehenna.”

Gehenna is merely the ultimate and eternal form of anarchy. This is to be kept in mind when humanist Darwinists, including most college professors, are reminded by a fellow academic of the rank inconsistency of their references to moral norms as they recommend, say, the ethical stance of civil disobedience in fighting against racial inequality. In coming to the aid of one such academic (Prof. D. Kagan), Prof. L. Pearce Williams of Cornell wrote in a letter to the New York Times in December 1983 of the vanishing of the moral world with the end of Victorian times. He also noted that our world today is a mere consensual world, which, in view of the progressive break down of consensus, is rapidly heading toward anarchy.

As a historian of science, Prof. Williams could hardly fail to think of Darwin’s work, which prominently figured in the assault made on the traditional moral world in precisely those times. His failure to point that out and to recall the repeated disillusionment of eminent Daiwinians with Darwinism shows once more that the only thing man learns from history is that he never learns from history. But those who do not wish to take seriously the lessons of history are bound to help usher in historic disasters.

They do so by cultivating horrendous somersaults in logic whereby all things, big and small, trivial and stupendous, appear to evolve—or as the Romans of old would say, unroll—from under wrappings that seem outright pleasant. For nothing pleases nowadays more than academic respect ability even if it is a cover-up for committing one big mental robbery through uncounted petty thefts-all of which are made imperceptible by phrases hollow inside their learned exterior.

Leave a Reply